More than three decades ago, Carlo Di Ruocco, an Italian expat who’d recently moved to Oakland with his wife and young kids, quit his job as an elevator technician to build a coffee company. Thirty-seven years after founding Mr. Espresso, Di Ruocco has grown the family business into a vital part of West Coast espresso culture.

Mr. Espresso sells and services espresso machines and roasts coffee for clients; Carlo Di Ruocco’s son, Luigi Di Ruocco, also independently owns San Francisco’s Coffee Bar chainlet. Mr. Espresso simplified the process of importing machines for restaurant owners who didn’t want to navigate customs and shipping when it launched in 1978, and a few years later, Di Ruocco began supplying roasted coffee to restaurant and cafe owners.

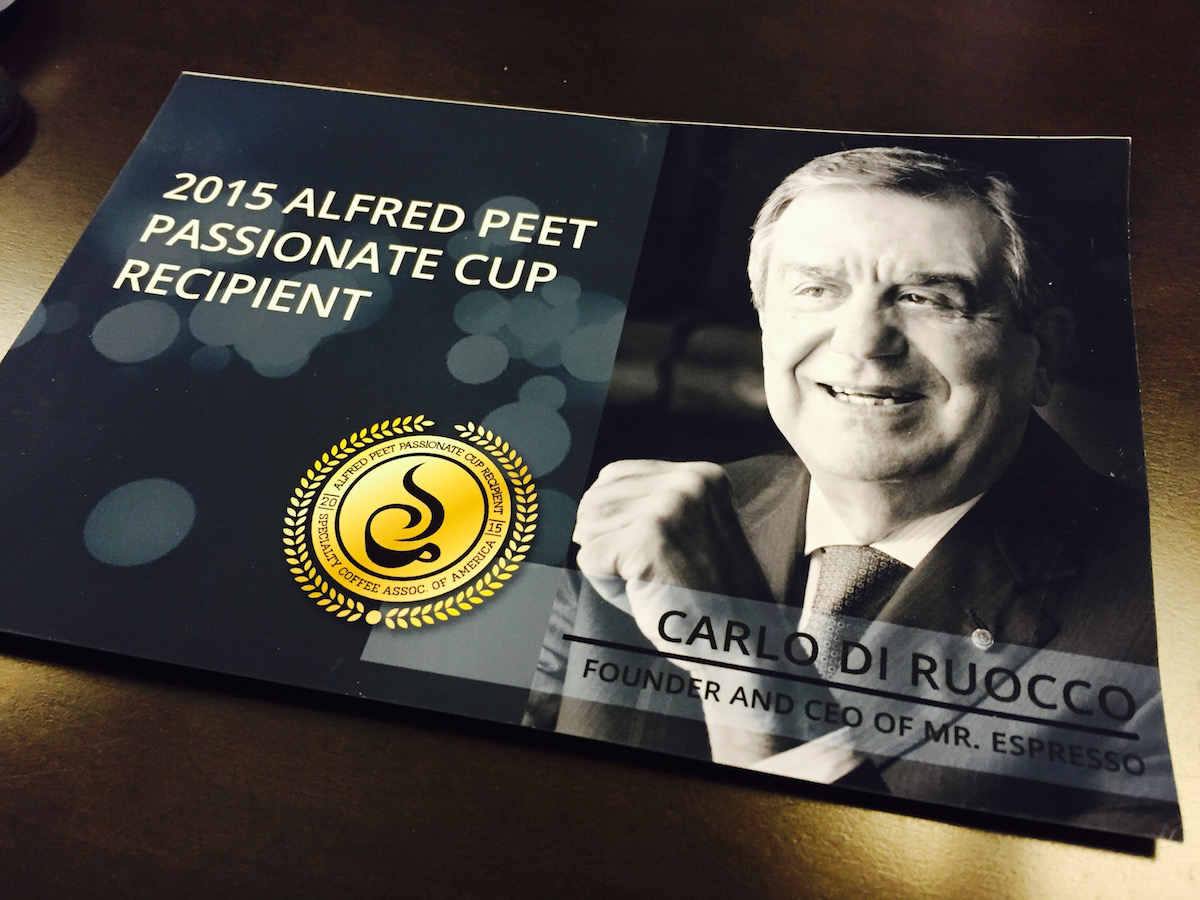

Mr. Di Ruocco, who speaks with a beautifully intact old world accent and looks like the suit and tie were invented for his own personal use, sat down with Sprudge during SCAA in Seattle. Our conversation with him happened the day after he was given the Alfred Peet Passionate Cup Award, a lifetime achievement honor given by SCAA during the organization’s annual awards ceremony, for which he received a standing ovation. And since we’re gushing: not many lauded coffee professionals can claim that they’re also knights. In 2009, Di Ruocco received an honorary knighthood from the Council of Italy for championing authentic Italian espresso in the US.

Di Ruocco grew up around coffee and was first exposed to espresso by his mother. “To have more energy she was drinking espresso all the time, because she worked 18 hours a day or so,” he says. “I grew up without a father. There were seven children and we had to grow up working. There were a couple of farms around us where I worked for food.”

His first paid job was in a cafe while he was a teenager living in Salerno, Italy. He remembers espresso costing 10 cents and each street downtown housing three to five cafes. Back then, he would drink 15 or 20 shots of espresso a day. Now, he drinks five max.

After two years, he quit his job at the cafe, where he earned a quarter per shift, to work as an electrician for $2 a day. He had a knack for fixing equipment and found a job as an elevator mechanic when he moved to France two years later. That’s where he met his wife, Marie-Francoise Di Ruocco; theirs is an enduring love that continues to this day, after 53 years of marriage. Carlo Di Ruocco’s transition to America began in 1967; after a brief return to Italy in the early 70s, the entire Di Ruocco family moved to Oakland in 1974 and has lived in nearby Alameda ever since.

In the States in the late ’70s, Di Ruocco was rooted in a career in the elevator business, but that all changed when his brother asked for help importing an espresso machine for his nearby restaurant. “I came to San Francisco and no one was drinking espresso. There were a few machines around the Bay Area, but they were old and they were not great at making espresso,” Mr. Di Ruocco told me. “And there were no mechanics to fix them. So being an elevator mechanic who worked in coffee in Italy, we were fixing our own machines. So we had the idea to start bringing espresso machines to the Bay Area because there was a market and no one was able to repair them.”

Di Ruocco worked 12 hour days for the first years after starting Mr. Espresso, all while keeping his job as an elevator mechanic. “I was selling and installing machines after work and on the weekends with my 11-year-old son,” he remembers.

In 1981, he told the owner of the [elevator] company where he was working that he was leaving to start a business. “He said, ‘You’re crazy. You are making the same amount of money as Jerry Brown,’” Di Ruocco says, smirking. “Jerry Brown, in 1978, was governor and he was making $60,000 a year, and that’s the money I was making in those years.”

Saving enough while working both jobs helped launch the company on solid footing, and by 1982, Mr. Espresso was importing 30 to 50 machines each year. One of Di Ruocco’s earliest clients was Alice Waters; he started supplying coffee to her Chez Panisse restaurant in the ’80s.

Di Ruocco says that it took more than a decade for espresso culture to really catch on in the Bay Area. When it did, things “changed like night and day.” In 1984 and ’85, he says, “nobody was serving a decent espresso, because of the machines and because there was no coffee made for espresso. Somebody used Colombia, somebody used Guatemala, the coffee was not roasted the way in needs to be for the espresso machine.”

He says it’s only been in recent years that there’s been a coffee boom, and says that’s a good thing. “Now you have a lot of new roasters and drinkers. That’s what we like,” he says. “The more the quality goes up, the more people will drink coffee.”

Looking back on his career, Di Ruocco says he wouldn’t have imagined working in coffee professionally and building a decades-old business around it. He says in Italy, “I had a good life, but … it was no challenge. I needed a challenge, to create and do something. I always imagined that one day I’d go some place.”

The challenge ahead for Mr. Espresso is maintaining relevance and growth in an industry that’s currently bent towards light roasts. “We’re trying to focus on the message of our history and how it fits into the landscape today,” Di Ruocco’s son Luigi says. “To be aware and make the right types of adjustments but also not leave behind our story. We have to take care of our story and also mold it properly for the future.”

Luigi and other members of the Di Ruocco family were on hand to see Carlo accept his award at SCAA. “The whole family was pretty emotional,” the younger Di Ruocco tells me, and who can blame them?

“It was too touching,” the elder Di Ruocco tells me, adding that before he could even take the stage, Tim Castle’s introduction speech had moved him to tears. “I could not say what I really wanted to say, but the people were wonderful and understood.”

At 80 years young, Carlo Di Ruocco is in the office most every day but says he’s “more relaxed” now. Still, if he doesn’t like something, he’ll say it. “The most important thing is that the family is all together working for Mr. Espresso,” he says. “That’s maybe the biggest accomplishment of my life. Everything else comes second.”

Sara Billups is a Seattle-based food and drinks writer, and has written previously for Tasting Table, Seattle Weekly, and Eater Seattle. Read more Sara Billups on Sprudge.