David Lynch is clearly a man who loves coffee.

He features coffee prominently in his work. He’s said in interviews that he drinks up to 20 cups a day. He once launched his own coffee brand with a terrifying video where he talks to a Barbie doll.

I am a specialty coffee professional. My job is to understand everything I can about what makes coffee delicious and figure out how to apply it as broadly as possible so that my customers can enjoy delicious coffee. It would be reasonable to think that I would relish the opportunity to meet Mr. Lynch and serve him a cup of coffee, given how much he loves it and how I’ve dedicated my professional life to it. This is not the case, however. That’s because I have seen Lynch’s 2001 film Mulholland Drive, and therefore the idea of serving coffee to David Lynch terrifies me.

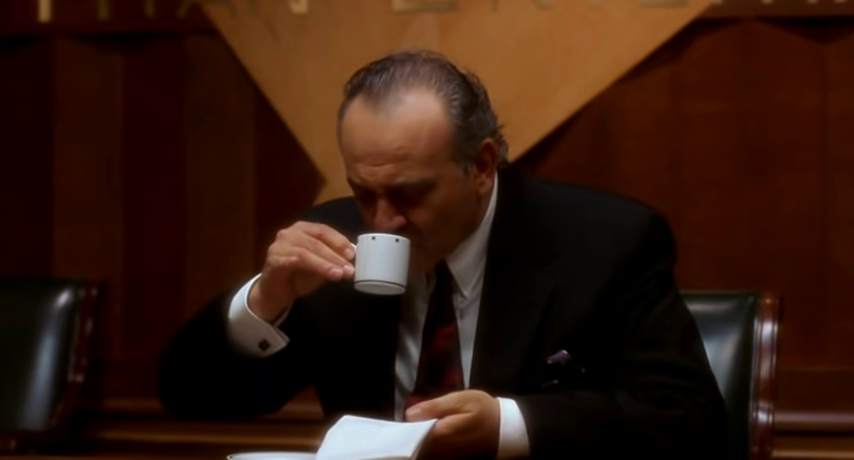

Around 30 minutes into Mulholland Drive’s runtime, a film director named Adam Kesher (played by Justin Theroux) goes into an office building to have a meeting about his new project with his producers. Shortly after sitting down, a pair of imposing men in suits arrive and are introduced as the Castigliane brothers. We never know exactly who the Castigliane brothers are, but we soon find out that they’re very powerful and can ruin Adam Kesher’s life if he doesn’t play ball. We do know that they’re intimidating (given how the producers react to them) and that they have demands. They want a woman named Camilla Rhodes to be in Adam’s movie, and one of them wants an espresso.

The brother who wants an espresso is played by the man who composed the music for the film: frequent Lynch collaborator Angelo Badalamenti. Badalamenti did not act frequently and had no training for it, but David Lynch is a man who knows how to use non-actors onscreen. He knows how to find a person with a particular physicality and look and puts them in front of the camera mostly to let them simply exist as a kind of living prop. Badalamenti exists in this scene to do two things: look intimidating and express disappointment.

Adam is flummoxed at having been told that he needs to cast an unknown woman in his movie, but the producers are more concerned with the espresso. “I think you’re going to enjoy the espresso this time. We’ve done quite a bit of research, knowing how hard you are to please. This one comes highly recommended,” one of them tells Badalamenti. A couple of minutes later as Adam continues to protest, a man in a red jacket comes in with Badalamenti’s espresso. As he nervously places it in front of him, Badalamenti whispers the word “napkin.” As the waiter fetches the napkin, the room falls silent as nervous energy builds. The men stare wordlessly at each other until Badalamenti places the napkin on his palm, uses his other hand to take a sip of espresso, and after an incredibly tense beat spits and drools his espresso onto his napkin. After wiping his chin, he gives his single word review of his beverage: “shit.”

The producers—literally quaking in their seats—jump into damage control mode. “I’m sorry! That was a highly recommended… that is considered one of the finest espressos in the world!” they sputter out. Badalamenti rises, does not meet their gaze, mutters “this is the girl,” and leaves the meeting. For the next hour of the film after Adam does not immediately comply, unseen forces conspire to strip him of his romantic relationship, his prestige, and his bank account, all over an actress (and an espresso).

Film remains a medium that can only express sight and sound, and so we as the audience do not know what that espresso tasted like. We aren’t given tasting notes or tactile descriptors. We don’t know if the espresso is round and balanced or bright and sparkling or thick and chocolatey. We only know that the espresso is “considered one of the finest espressos in the world.” We do not know the provenance of this coffee, but it’s entirely reasonable to think that a farmer grew it with great care to sell it on the specialty market, and that a roaster painstakingly roasted it to fit what they thought was a perfect espresso profile, and that the barista took the time to dial it in and make sure that the espresso extracted perfectly, and that this man still thinks that it is “shit.”

When people talk about David Lynch and coffee, they rarely point to this scene to showcase his love of the drink; instead, they point to Special Agent Dale Cooper from Twin Peaks. Coop practically made “that’s a damn fine cup of coffee” into Twin Peaks’ catchphrase, and is the star of a Lynch-directed advertising campaign for a Japanese canned coffee brand called Georgia Coffee. Dale Cooper seems to be a kind of stand-in for Lynch himself in the show, sharing Lynch’s love of coffee, his chipper can-do attitude, and his love of Tibetan Buddhism and meditation. We see one glimpse into Cooper’s taste in his breakfast order: “two eggs over hard and bacon, super crispy, almost burned, cremate it.” This is not a breakfast that would pair well with a sparkling Kenya SL-28 or a delicate and floral Panama Gesha, no matter how much I might pay for those coffees or how well esteemed they might be.

If I served those coffees to Cooper, he might not react the same way as Angelo Badalamenti does in Mulholland Drive, but only because of how polite Cooper is. He might internally want to drool it all over his napkin and exclaim that it’s “shit”, and who am I to tell Dale Cooper that he’s wrong for not enjoying a cup of coffee? Coop’s breakfast would pair beautifully with a Colombia Caturra with a little more development on the roast, with a muted acidity and some sugar browning flavors. This would be a more commonplace coffee, and likely one that would cost less than the rarer SL-28 or Gesha, but I could not look Dale Cooper, David Lynch, or Angelo Badalamenti in the eye as they sipped and enjoyed such a coffee and tell them that it’s “worse” objectively.

It’s very easy to mistake descriptive quality for objective enjoyability in all things pleasurable, and coffee is no exception. A skilled coffee taster can objectively say that a coffee has a more intense acidity than others, or that it’s sweeter, or has a fuller body, or has a pronounced aroma of bergamot and jasmine. The marketplace can dictate that a coffee with these qualities is rarer than others and thus commands a higher price. A roaster and a barista can work to make that coffee express these qualities in the cup with years of expertise and knowledge and perfectly calibrated equipment. A person can still take a sip of that same coffee though and drool it all over their napkin and express their disgust with it. I as a barista cannot plead with that person and say “that is considered one of the finest espressos in the world” and suddenly expect them to change their mind.

I cannot speak for my profession as a whole, but I got into the specialty coffee industry because I wanted to share something delicious and wonderful and special with the world, and I know that I’m not the only person who feels this way. It’s very easy to lose track of what you’re doing in this space and think that those who do not share our taste are simply uneducated rubes who will drink any swill you put before them. Every time I think that I’ve cracked the code and have found the one true way to prepare a coffee, and dial in the “finest espresso in the world,” I think of Angelo Badalamenti drooling on his napkin, and I get back to work, trying to figure out something else that he might enjoy.

I may not fully understand Mulholland Drive, but it keeps me humble.

Jackson O’Brien is a coffee professional and freelance journalist based in Minneapolis. Read more Jackson O’Brien for Sprudge.