Carrots, okra, corn, bread, tortillas, lupin beans, fava beans, chickpeas, rye, wheat, buckwheat, barley, spelt, malt, corn, peanuts, chestnuts, almonds, figs, carobs, sunflower seed husks, persimmon seeds, watermelon seeds, sweet potato, acorns, hawthorn, blackthorn, chicory, dandelion, artichoke, mate, yaupon holly, Kentucky coffeetree, date pits, fenugreek, sugar beat, a variety of mushrooms, maca root, cacao.

Toasted. Ground. Infused with hot water. Referred to as…

Coffee?

It turns out, coffee can be a bit of a loose concept once we develop a taste for it. For nearly 200 years, scarcity, austerity, and ingenuity have all helped coffee drinkers drink coffee that, well, isn’t coffee.

Now, 21st century health concerns and a booming beverage market drive entrepreneurs to launch new coffee substitute products using some old school recipes and some new tricks. But what exactly are these drinks substituting? And why are we faking our coffee in the first place?

Austerity and the Homemade Solution

Yes, coffee comes from the plant of the genus Coffea, but once we get to know its flavor well enough, we can abstract it into an idea. Like artificial flavorings, we can call something by its taste, even if it doesn’t contain that ingredient. But with coffee, a substitute is more than just a flavor profile. It is also a ritual, a stimulation, and, perhaps, an addiction.

The first coffee substitutes emerged as homemade solutions to shortages only after coffee became a mass produced and consumed commodity in the 19th century. Drinkers needed to develop a habit first if they were to seek out a replacement for their daily cup. By the mid 1800s, substitutes began to emerge.

Soldiers in the US Civil War used persimmon and watermelon seeds, roasted sweet potatoes, and peanuts. Nebraskans on the frontier in the 1860s used dried barley, rye, or corn in addition to dried carrots and okra seeds. West Virginians reported a recipe that mixed wheat bran with corn meal, eggs, and molasses. New Mexicans used jojoba (sometimes called the coffee bush,) burnt wheat, sunflower seed hulls, juniper berries, and other native seeds.

Back in those days, it seemed that mimicking coffee’s roasted flavor was a top priority, while caffeine was secondary.

The First Wave of Commercialization

German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge first isolated caffeine from coffee in 1820. By the end of the century, the chemical was under scrutiny. Was caffeine, and also coffee, good for our bodies?

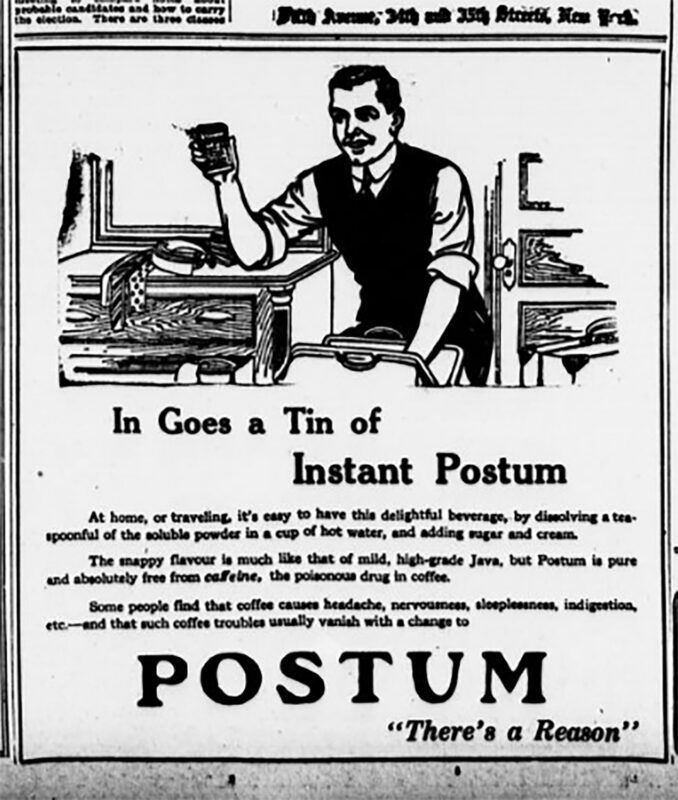

C.W. Post founded Postum in 1895 to address what he saw as the poisonous effects of caffeine consumption. He marketed the mix of wheat bran and molasses as a health beverage with various medical claims and anti-caffeine rhetoric. The brand took off.

Dr. Lauren Alex O’Hagan, Research Associate at the Open University’s Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies, has researched Postum’s expansion into Sweden. In the early 1900s, Swedes in positions of power debated kaffemissbruk, or caffeine abuse. She says that Postum “tapped into broader concerns at the time about the dangers of caffeine on health. Early advertisements emphasized the ‘caffeine danger,’ describing caffeine as a poison and using scaremongering techniques to convince people of an alternative drink.”

Reflecting on how such a substitute can emerge, Dr. Alex O’Hagan adds, “I think the embedment of coffee in society is integral to debates around substitution. In the early 20th-century Swedish context, drinking coffee had grown into a major cultural institution, part of the country’s fika ritual, so it was very important in people’s lives. Coffee substitute companies like Postum had a challenge on their hands to convince them to switch, which is why they seemed to tap into the health element of the substitutes as a motivator.”

Unlike the homemade substitutes that resulted from scarcity, most 20th century Americans and Swedes had access to coffee. Commercial substitutes sold themselves as permanent changes to diet for health reasons, not bandaid beverages covering a pantry deficiency. Invariably, Postum and its 20th century competitors removed caffeine entirely, as it was how they sold their product.

The New Wave of Commercialization

Postum is still alive. Food giant Kraft eventually acquired the old-school brand but discontinued it in 2007. Then, in 2012, lifelong Postum drinkers, June and Dayle Rust, founded Eliza’s Quest Foods, bought the Postum recipe and brand, and put it back on the market.

Postum bridges the two waves of commercial coffee substitution. June Rust explains how they have steered the brand in the last decade, “In the beginning, our focus was to resume the old customers, let everyone know that Postum is back. Now we are in a different place, we see what’s going on in the coffee replacement space. We are looking at developing SKUs that are more trendy. And we will hold onto our vintage Postum. You cannot ignore history.”

Postum is not alone, according to Data Bridge Market Research, the caffeine substitute market could be worth $2.37 billion by 2029. Many new brands echo Postum’s original health message, but the modern message is a bit more nuanced.

Rasa, now on the market for about five years, approaches the coffee substitute questions from an herbal, adaptogenic point of view. Ben LeVine, Co-Founder and Chief Herbalist, explains, “Coffee is so embedded in our morning ritual and it doesn’t work well for everyone. Some people are starting to think, ‘Maybe I feel better with less caffeine or no caffeine.’ That’s where Rasa comes in because the herbs we use are a good energy tonic and they are better with habitual use.”

As a substitute, Rasa looks to emulate coffee’s energizing effects, its daily ritual, and its flavor. “Our formulas have two parts. The taste coffee-like part, which is often not adaptogenic. Chicory, roasted date, roasted burdock.” Continues LeVine, “Then, on the adaptogen side we follow a lot of traditional formulas and pair it with wonderful studies and research to get our dosage.”

MUD\WTR, around since 2018, has a lightly caffeinated product that relies on cacao, masala chai, turmeric, and a variety of mushrooms. Founder and CEO, Shane Heath says that the product is a substitute in that it replaces the ritual of drinking coffee.

“When we call our product a coffee alternative, we are replacing the habit more than we are trying to mimic the taste.” says Heath, “Our flagship blend, :rise Cacao, tastes and smells different (think chocolatey-chai with a kick of turmeric and cinnamon), and—most importantly—affects drinkers differently than coffee. Between the low caffeine content and roster of functional ingredients, it delivers focus and energy without the downsides of coffee, like jitters and a crash. The only way it resembles coffee is as a morning ritual.”

Then there’s the brand Kein Kaffee, German for “not coffee,” soon to launch in the States. It is based on lupine beans, a substitute that has roots in World War I shortages in Germany. Matthias Weimer saw a resurgence in interest in Germany and took an immediate liking to the drink. “Kein Kaffee is the perfect substitute for coffee due to being biologically very similar as they are both made from beans (compared to most other coffee alternatives that are made from roots or mushrooms).” He says, “So when you roast a lupine bean, the same chemical reactions take place as in a coffee bean, which results in a strikingly similar taste. The same goes for the ritual and brewing temperature, as Kein Kaffee behaves just like normal coffee and is suitable to be used in any way you prepare your coffee.”

These companies are not alone. Other new brands take traditional substitutes and reintroduce them to the modern audience. MEDIDATE sells date pit coffee typical in the Middle East, Teecino makes dandelion and chicory brews, and Yaupon Teahouse and Apothecary sells yaupon tea “espresso style” native to the US South.

While coffee substitutes are a cultural and gastronomical phenomenon, there is also some objectivity about them. Many of the historical and modern substitutes contain chemicals called furans, which are the aromatics responsible for coffee’s roasted odor. Other substitutes are high in chlorogenic acid or vinyl guaiacol which are both present in coffee.

Whether we make coffee from burnt tortillas or lion’s mane mushrooms, we can reflect on why we are calling the drink coffee in the first place. Is it the flavor? The stimulation? The morning ritual? The hot liquid in a ceramic mug? If anything, coffee substitutes are a testament to the power that coffee has over our daily lives. If it wasn’t so powerful, we wouldn’t feel the need to substitute it in the first place.

N.C. Stevens is a freelance journalist based in Boston and the creator of DrinkingFolk.com. This is N.C. Steven’s first feature for Sprudge.