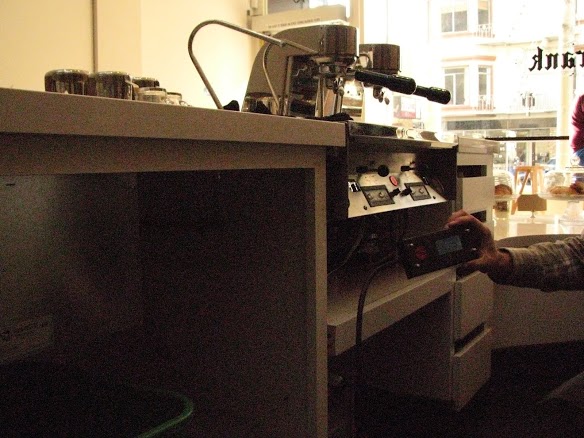

There’s a shiny little bit of kit that adorns the front counter at Saint Frank, a new cafe in the Russian Hill neighborhood in San Francisco owned by barista turned cafe proprietor Kevin Bohlin. Lovingly designed and handcrafted by the engineer/designer John Ermacoff (otherwise known as Jepy), this two grouphead, under-the-counter espresso machine is called either the Minim (if you ask Ermacoff) or the Ghost (if you ask Ben Kaminsky, a Zelig-like speciality coffee consultant involved in the project’s design). The machine in use at Saint Frank is the first iteration of Minim/Ghost, and will soon be joined by a slightly updated sibling on the same bar.

I spent a day talking service, design, and aesthetics with Mssrs. Bohlin and Kaminsky, and quickly realized that this isn’t just a trick new piece of gear – the Jepy machine was chosen as an integral part of an entire service philosophy.

Saint Frank is what I think of as a concept shop. It’s based on ideas rather than things or atmosphere – one of those ideas is that the equipment shouldn’t stand between the customer and the barista. Another thing struck me right away: the service is influenced by barista competitions, rather than the other way around. It makes sense if you know Mr. Bohlin, an experienced and talented barista competitor for his former employer/current sourcing partner Ritual Coffee Roasters.

The gear and layout at Saint Frank was designed with the express purpose of helping Mr. Bohlin and his staff enact those service principles previously perfected on the competition stage. Bohlin said he fell in love with the Mahlkonig K30 Twin coffee grinder after practicing on it for competition – Saint Frank sports two such grinders – and the Jepy machine is so low profile it makes receiving barista-competition-style informative lectures from the barista a total breeze.

The drinks at Saint Frank are also competition-inspired. The bar is set up to run two espresso recipes for each espresso, and it’s all a matter of pushing two buttons. The two K30 Twins on the counter are dialed so that one hopper on each is for small drinks and the other is for large drinks. The Jepy machine is set up to pull two different styles of each espresso using volumetric dosing and programmed pressure profiles. The whole process is seamless. The barista takes orders, the K30 grinds, tamping happens front and center, and the Jepy machine is practically invisible, allowing the barista to easily discuss the coffee or anything else with the customer.

In talking to Mr. Bohlin, I realized that this transparency in service extends to his ideas about the rest of the industry. He uses coffees he sources himself or sources through his continuing partnership with Ritual Coffee Roasters. He wants to tell you about the farms and the farmers. He doesn’t want to talk about the brew method or the machinery involved in roasting or brewing. He wants to tell you about where the beans came from even before you order something. This kind of discussion is made all the easier because of the Jepy Ghost/Minim.

Such a minimal and singular machine does require some degree of explanation. Bohlin says that customers sometimes come in and ask, “Just brewed coffee? No espresso?” – all while he’s making an espresso drink on the Jepy machine. Or, more than once, customers have asked where the espresso machine is, as he’s making their drinks. This is just the kind of displacement of attention that Bohlin is going for, and begs a larger question, one that many speciality coffee bars are asking in 2014: What if we don’t focus on the machine?

But somebody has to think about the machine. John Ermacoff/Jepy has been thinking about making coffee for years. I first encountered his Flickr account around 2008 or 2009. The Jepycoffee Flickr stream is still full of espresso futurist ideas and designs that haven’t been realized or haven’t proved practical. It’s Ermacoff’s engineering that made the machine a reality.

When I’ve brought up the name Jepy, some people have intimated he’s mostly making espresso machines out of Synesso spare parts. Based on what I saw at Saint Frank that’s both true and not at all true. It shares some electronics with the Hydra, and it has the same kind of two-pump setup. But the groupheads and boilers are all custom machined in Redwood City. Really, it shouldn’t be leveled as a criticism that some parts are repurposed – standardized parts only make the Minim/Ghost that much easier to repair.

At this point in my Saint Frank visit, Kevin had foisted me on Ben Kaminsky, who again, Zelig-like, just so happened to be in the shop. Kaminsky had consulted on both Saint Frank and the Jepy machine. “The Ghost [Kaminsky’s name for the machine] is temperature stable within 1 degree Farhenheit and its energy needs are less than half of those of the Modbar,” Kaminsky told me. The Modbar, if you’re unfamiliar, is another under-counter espresso machine that made great waves in 2013, ultimately winning our Sprudgie Award for “Best New Product” just a few weeks ago. Mr. Kaminsky tells me of the Ghost/Minim: “Within six months I think we’ll have a machine that could be called the best espresso machine in the world.”

While Ermacoff seems in charge of the engineering, Kaminsky claimed a degree of authorship over the machine’s under-counter design. Bohlin assured me that it was super easy to service – the machine even pops up for easy access to the inner workings. Bohlin is all-in on Jepy, but he didn’t do that without first asking a third party tech, Kyle Waters, whether he could service the machine. After Waters gave the go-ahead, Bohlin committed to two of the machines. The second will be delivered with a few minor upgrades later this month.

And that’s where this first leg of the journey into the inner workings of the mysterious Jepy ends. In the coming days I’ll be traveling with Ben Kaminsky to John Ermacoff’s Jepy workshop in the nearby San Francisco suburb of Redwood City. This is something of a first in the annals of coffee journalism, for while Mr. Ermacoff has long been a well-respected voice in the development of speciality coffee technology, my forthcoming coverage will be the first public look inside his secret espresso engineering skunkworks. Stay tuned.

Leif Haven (@LeifHaven) is a Sprudge.com staff writer based in Oakland. Read more Leif Haven on Sprudge.