A few weeks ago we published Sprudge contributor Albert Au’s guide to the 5 top cafes in Hong Kong. During the research phase for this feature, Mr. Au conducted a number of interviews with cafe owners, baristas, and coffee professionals throughout Hong Kong. A narrative emerged: Hong Kong’s coffee scene has come so far, so fast, but is the trend sustainable? And is it merely just a fad, or part of some wider movement? We rejoin Albert Au on the streets of Hong Kong.

I started my last article for Sprudge by talking about how new the Hong Kong specialty coffee scene is. The abundance of high-quality cafes dotting the city today does not resemble the Hong Kong where I was born; specialty coffee came to Hong Kong only a few years ago, and it’s gone through a huge boom in a short time. How did this happen? And is it sustainable? I had a chance to ask these questions to some industry leaders in Hong Kong, folks like Kapo Chiu (The Cupping Room), Jennifer Liu (Coffee Academics), Patrick Tam (Knockbox), and many more. Their answers may surprise you.

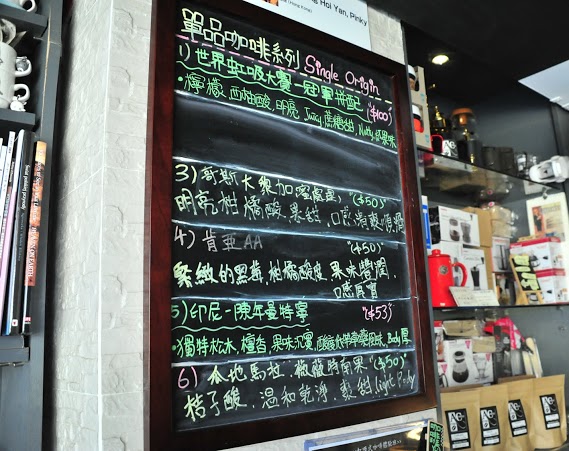

Opening a coffee shop presents certain risks and challenges no matter what the market, but trying to open in Hong Kong can be particularly challenging. One of the biggest issues is the high rent, which results in higher costs across the board for running a cafe in Hong Kong. Reuters says Hong Kong has “the world’s highest rent for prime retail properties,” with some districts being up to 4 times as expensive as London and Manhattan–as much as $4,328 per square foot in rent! That’s not everywhere in town, obviously, but it gives you some sense of how expensive it is to own a cafe here. These prices are at least in part passed on to the customer, which is why it costs around $5 USD on average for a 150ml sized flat white. For filter coffees, it’s even more expensive, with an average “specialty grade” filter running around 8 or 9 US dollars a cup. Particularly rare coffees can easily cost 10 dollars or more.

This may in part explain why so many cafes in Hong Kong offer food: none of them can really do coffee as a single source of income. A food menu and other beverages are necessary just to make the business sustainable.

To learn more, I talked with folks throughout Hong Kong’s coffee scene, at many of the places I profiled in my previous article on HK coffee. First up, I spoke with Jennifer Liu, who is one of the main people behind the brands The Coffee Academïcs, Suzuki Café and Café Habit?. She opened The Coffee Academïcs as a specialty coffee roastery to supply her other brands and help to educate people on the importance of understanding coffee from seed to cup. “The specialty coffee scene had really just started here,” Ms. Liu told me. “Although much has emerged already, there will still be a lot more to come. Hong Kong’s coffee scene has already reached the world level and people will carry on pursuing coffee knowledge.”

Ms. Liu sees consumer awareness as a big trend in Hong Kong as understanding increases among the public for why specialty coffee is special. More and more coffee drinkers in Hong Kong appreciate the effort put into a fine cup, and understand the associated costs.

That is perhaps a rosy picture, though I like Ms. Liu’s optimism. However, with the nature of extremely high rent in Hong Kong, the business environment in HK is naturally quite competitive. Many cafes will not survive long; only the best could stay. Tsuyoshi Mok, owner of Accro Coffee and judge for the Hong Kong Siphonist Championship, has a more pessimistic view of the situation. He worries specialty coffee in Hong Kong is a bubble that might burst in a few years’ time. In light of this, Mr. Mok says, “what’s important is the passion within people.” People who want to “introduce something and stick with their initial purpose.”

This feeling is echoed by Kammi Hui, trainer at 18 Grams and a World Barista Championship sensory judge. “This is a fast-paced market,” she told me, with “an average of one new ‘specialty shop’ opening every other week.” She hopes that this is not a fad like other businesses that came and went in Hong Kong, “like Taiwanese bubble tea. Ten years ago there were countless shops. Now it’s hard to find even one.”

But it’s not all dire. Kapo Chiu, two-time HK Barista Champion from The Cupping Room, thinks that people in Hong Kong are more open than ever to accepting a new coffee culture. Importantly, he’s seeing more and more baristas in Hong Kong who are willing to develop their skills and take this job as a proper career. This is something of a change: a lot of people in Hong Kong are still quite traditional, and while many in the younger generation in HK are highly qualified to become things like doctors or lawyers, more and more people each day decide instead to become coffee professionals. Mr. Chiu believes there will be even more specialty companies to come, and that they’ll be here to stay, so long as they can afford the rent.

There’s also something of an ongoing dialogue in Hong Kong over what “specialty coffee” really means. Patrick Tam, co-owner of Knockbox cafe and roastery, and one of Hong Kong’s first accredited Q-Graders, told me that in the past 3 years a lot of specialty shops have opened that are not truly specialty grade. “Their coffee is at most high quality commercial grade,” says Mr. Tam (without naming names). “They seem to be more focused on their [barista] skills and got confused on that being ‘specialty’, and not the coffee itself.” Mr. Tam would instead like these kinds of places to be labeled “craft coffee” instead of specialty, which may sound like semantics to some, but could be an important distinction in a new scene like Hong Kong’s.

When Knockbox first opened, his shop’s focus was more on filtered coffee (often called “soft brew” in HK). Almost 80% of his early sales were filtered brew. Now he is proud that the ratio is more or less 50/50 on soft brew and espresso. Local residents in Hong Kong are trend followers, and if Mr. Tam’s sales are anything to go by, espresso is more a part of the specialty coffee trend than ever in Hong Kong. As for the wider trend, the hype of specialty coffee could recede in the coming years, Mr. Tam concedes. But he doesn’t think this is likely.

“Trends will come and go,” he told me, “but the public will not be able to resist the high standard of coffee after they have tried it. They will continue to seek specialty coffee even if the hype ceases and the total amount of new specialty shops decline.”

To get back to our central question, I think it’s safe to say that specialty coffee is very trendy in Hong Kong right now. It could be that Hong Kong’s exciting new coffee culture is headed towards a “bubble burst” moment, like so many popular fads that have receded in the past. We may not continue seeing “one or two new shops a week” in Hong Kong, as mentioned by Kammi Hui, and the city’s very high rents will continue to pose a barrier that only the best shops can survive in the long term.

But high quality coffee makes a very strong argument for its own existence, and deliciousness is hard to ignore, even at expensive prices. Hong Kong’s coffee scene is growing right now, and it makes for a fascinating community of talented coffee professionals and beautiful cafes. I respect the hard circumstances facing many specialty coffee professionals in Hong Kong, but in the end, I’m an optimist. I believe specialty coffee has come to Hong Kong for good.

Albert Au (@albertacp01) is a working barista, photographer, and journalist based in Auckland, New Zealand. Read more Albert Au on Sprudge.