It’s an unfortunate aspect of the coffee industry that in many of the places producing coffee, gender equality does not exist—unfortunate, but not unalterable. The Coffee Quality Institute’s Partnership for Gender Equity is tackling this issue in a three-step approach, the first phase of which began this November in the form of a research report entitled “The Way Forward“.

CQI’s Kimberly Easson is the engineer of this initiative. She enlisted Susan Cote, Inge Jacobs, and Colleen Anunu to work with her on this stage of the process. Each of the four women had a different role in developing, collecting, and collating the research presented in the report, and each brought a different perspective to gender equity in conversations I had with them—parsing out the details of the report, their approaches to research, the difficulties of undertaking such a large and complex issue, and the factors that can make gender equity efforts more sustainable. Their report is worth reading even if you don’t work in coffee, but is an essential read if you do. What follows are my takeaways from the report, and Easson, Cote, Jacobs, and Anunu’s expansion on specific areas.

Gender equity: good for people, good for coffee.

One thing the 75-page report stresses from multiple angles, and through diverse evidence, is that gender equity is good for people, is the right humanitarian action, yes, but more than that, gender equity is good for coffee—good for the coffee business.

Susan Cote, who formerly worked for Green Mountain Coffee heading up its marketing division, used her expertise to craft an industry input plan for CQI, conducting focus groups and interviews with a broad spectrum of coffee professionals and industry leaders to better understand what would make them more interested in participating in gender equity projects, what concerns they had about promoting gender equity at origin, what they’d already been doing to promote gender equity in coffee, and how much the industry generally understood the issue.

Cote feels businesses have a huge role to play in creating change. “That’s where most of our leverage will ultimately come from—the money to invest in programs, or the folks whose day-to-day decisions in the way that they conduct their business can impact the lives of producers,” said Cote.

Ultimately efforts are more sustainable, from a funding viewpoint, if they are win-win situations—if the efforts are effective not only in improving farmer’s lives and livelihoods but also make good business sense and improve the product.

“That isn’t just a crass profit-seeking motive,” Cote explains. “It’s because, ultimately, those efforts that are most sustainable are those that make business sense, that make sense for all the stakeholders. If only one party is benefitting, it makes it hard for any kind of effort to be sustained over time. If a for-profit business is doing things that don’t help that business and only help others, there’s a limit to how much of that they can do.” In other words, in order for aid from the private sector to have longevity, it needs to also help the businesses supporting it.

Stressing that gender equity aids the coffee business situates it within the context of all the other efforts being made to ensure an abundance of quality coffee. In many ways, the imbalance of gender rights can be considered as much a threat to the sustainability of quality coffee as global warming, access to water, plant disease, or an aging farmer population—issues that are (for the most part) more tangible, easier to directly address, and, therefore, have effort devoted to them more often.

Just think about this: women comprise half of the coffee growing workforce and are most involved in plant care, harvesting, and processing activities; however, they are often excluded from trainings and decision-making at not just the household level but also the farm and local organization levels. Plant care, harvesting, and processing—many would argue that these are the most important steps in creating high-quality coffee.

It’s in these essential steps, which arguably have the most impact on coffee plants’ health and crop and processing quality, that women do most of the work. It stands to reason (and the report verifies this through its findings) that making sure women have equal access to training as men, consulting with women of farming communities to see what aspects of training they’re most interested in, and pinpointing what factors prevent them from accessing not just training but credit and leadership positions is essential in improving coffee’s sustainability and quality, would benefit coffee as a whole. The more coffee workers with access to training and resources, the better for the coffee industry—especially if those workers are doing the bulk of harvesting and plant care.

Finally, monetary incentives make gender equity endeavors more sustainable for producers. Colleen Anunu did the background research and literature review on this subject—which involved reading many peer-reviewed studies and papers on gender equity and agriculture—and helped develop and conduct workshops that the CQI Partnership organized and participated in at four different coffee-producing regions around the world. Anunu pointed out the benefits of monetarily incentivizing producers to participate in gender equity actions. According to Anunu, coffee producers are growing a cash crop, which means there’s only one thing they can do with it—sell it. If you employ a methodology that enables farmers to see for themselves that practicing gender equity measures not only has the ability to produce a higher-quality crop but that doing so could also potentially enable them to enter into direct contracts with buyers who place a certain amount of priority on gender equity, those farmers will have two very logical, fiscally beneficial reasons to want to practice gender equity. Kimberly Easson, the chief architect of the project agreed.

“In the world of competing for new market opportunities, even companies just offering the ability to develop a relationship to establish a sourcing contract, that in itself can be a plus,” Easson says. Buyers can build incentives into those contracts—premiums, investments, trainings, or credit—that in and of themselves can be more inclusive of women but which also can be in exchange for better gender equity practices on the part of the producer. “Those practices could look like asking [the producer or producer organization] to have a gender policy in place or that there’s a person on the staff of the farmer organization or the producer entity that is accountable in some way for raising awareness about gender.” Easson says developing these sorts of incentives and policies is exactly what the Partnership and the industry should spend more time developing. However, she says, “It’s not unusual to do these kinds of things. We [the coffee industry] do it a lot with standards whether it be Fair Trade or Rainforest Alliance or quality standards—there are all kinds of buyer requirements that are already being put in to place,” so for Easson the question, now, is “how do we incorporate some gender measures as incentives or even just standards inside of a contractual agreement?”

The coffee industry and its concerns about promoting gender equity measures.

Cote, who conducted the industry focus groups; Inge Jacobs, who co-authored the report, is a human rights expert, and works for MARS developing women’s environment and gender strategy in the Ivory Coast; and Easson, all told me that they heard two primary concerns voiced by the industry in pursuing a push for gender equity. First: avoiding cultural imperialism or interfering in the personal and private lives of farmers. And second, ensuring that enough research had been done that their investments towards promoting gender equity would actually accomplish the betterment of farmers’ lives and livelihoods.

The second was generally a concern of very large companies who have to answer to investors. Easson is the first to admit that there is ample room for more research—you can never really have enough data, the issue is so complex and the specificities of each region (and regions within regions) are so different and so influential on the issue—but the report and the research that the Partnership has done has gone a long way to fill the void of information about gender equity at origin.

The first concern is a bit trickier. All four women admitted that gender inequity is a more sensitive issue to approach than, say, installing a well for a co-op’s use. However, that doesn’t mean that it can’t be approached or shouldn’t be approached, it just means that it’s much more important for companies interested in promoting gender equity at origin to know how to approach it in the right way without “overreach[ing] their boundaries in terms of telling a community what they should be doing,” as Anunu explains. “It’s more of an exploratory and evolutionary and participatory process.” That’s a large part of what this entire initiative is about; it’s why data collection and research and the workshops at origin that get farmers’ input and feedback are so important.

What it basically boils down to is this: gender equity doesn’t mean men versus women, it doesn’t mean barging in and telling people what to do, it doesn’t mean excluding men. Despite the apparent pervasiveness of these misunderstandings, that is not what gender equity (or gender equality, for that matter) actually means. Gender equity is, as the report says, “the process or approach of treating women and men fairly. It takes into consideration the different needs of women and men and includes measures to address women’s historical and social disadvantages. Gender equity is a means to achieve gender equality.” The UN, multiple human rights conventions, and most nations around the world support the value of gender equity.

In order to achieve a better understanding of gender equity and better gender equity practices, it is possible that certain cultural practices within a specific society might need to be addressed. There are entire books about cultural imperialism that decline to define it because the expression is a generic umbrella term that encompasses several roughly similar phenomena and the concepts of the terms “imperialism” and “culture” are so politically and intellectually complex that they cannot be defined “in isolation from their discursive context and the ‘real processes’ to which this relates.”

I will not attempt to define cultural imperialism in order to explain the difference between it and the recommendations in the report for promoting gender equity. What I will do, however, is assume that those industry concerns were generally coming from a place of respect for others and a desire to continue building good and meaningful relationships with coffee producers that empower them and better their lives. In that regard, the methodology and values recommended by the Partnership’s report are in complete alignment.

I’ll also echo the report in saying that, for the record, gender gaps exist in every country in the world. Yes, that means in the US, and in France, and England, and every other developed Western nation. While some of the highest inequalities can be found in coffee producing countries, they are by no means the only places where gender gaps occur and no one is stopping a company from implementing gender equity incentives in its contracts with farmers at origin and also taking a look at its own practices in the US and making sure that they support gender equity at home, too. Though this report focuses on gender inequity at coffee origin, it in no way confines the gender gap problem to just those locations. Rather, because those locations have such a large gender gap, have such a huge impact on the coffee industry, and have largely been neglected as far as addressing gender inequity is concerned, the report focuses in on them.

Should those seeking to provide aid or incite change have a deep understanding of and respect for the people they’re trying to help? Absolutely. Should they ask those people what it is they want and need in order to better their lives and future? You bet. Should the process be inclusive and participatory? Yes. Promoting gender equity doesn’t have to be divisive—in fact it shouldn’t be. Rather it should facilitate bringing people together. Promoting gender equity is an imperative, one that will not only help women but will also help men, families, farms, cooperatives, and coffee.

So how do you promote gender equity in a way that’s inclusive, participatory, and culturally sensitive? What can coffee companies do to promote gender equity?

The report details eight essential steps to promote gender equity at origin:

1) Increase women’s participation in training programs and revise training programs to be gender sensitive

2) Invest in programs to reduce time pressures for women

3) Improve women’s access to credit and assets

4) Achieve greater gender balance in leadership positions

5) Support joint decision-making and ownership of income and resources at the household level

6) Specifically source and market coffee from women producers and coffee produced under conditions of gender equity

7) Develop a list of gender equity principles for coffee

8) Continue to build understanding through research and measurement

The report then goes into detail about what each of these recommendations might entail, giving examples of farms or projects that exemplify the recommended actions and cautioning against unintended consequences that can be easily avoided. Speaking with Anunu, Cote, Easson, and Jacobs, all of them mentioned three methodologies they felt really worked to bring communities together to talk about gender inequity and to find some resolutions to common gender imbalances: Farming as a Family Business, Village Savings and Loan Associations, and Gender Action Learning Systems.

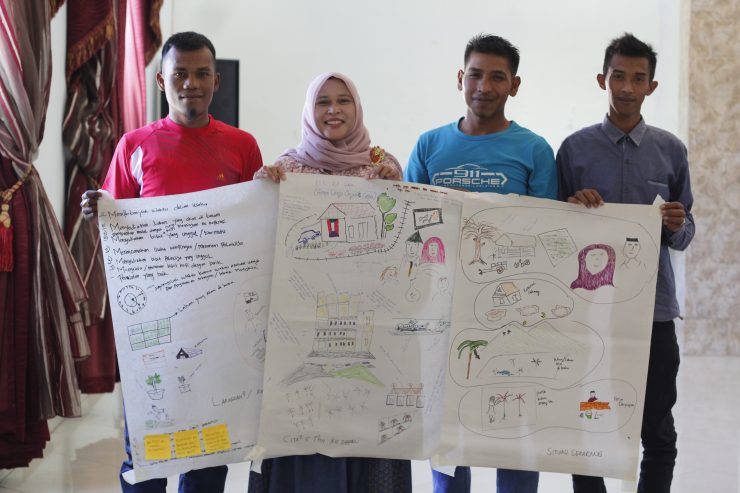

That last, which is commonly referred to as GALS, Easson and Anunu actually adapted to help them collect data at the workshops they conducted (and participated in) in Colombia, Nicaragua, Uganda, and Indonesia. The GALS methodology involves in-depth community training workshops that bring men, women, and communities together and facilitates open discussions about gender, gender roles, family responsibilities, gender-based responsibilities, community goals for the future, and the steps towards reaching those goals. GALS participants, as Easson said, “on their own, distinguish the power dynamics at the household level and the community level, the issues that they were facing and the barriers. They discover for themselves how gender imbalance impacts their well-being and their future vision for themselves, their families, and their children.”

Differences across cultures were placed in larger perspective. “In Uganda, there were very accepted behaviors of men that wouldn’t fly in Nicaragua. They wouldn’t fly in the United States,” said Anunu, citing a lack of women’s rights to hold assets or control income, or the permissiveness of gender-based violence—beating women. “It’s not necessarily this way all the time but some of the conversation that was generated about the things that women didn’t like about being a woman in their community was being beaten by their husbands, and one of the things that men didn’t like in their community and about their role of being a man was having to beat their wives,” said Anunu. “It was a very tough conversation to have.”

“It just breaks your heart,” Easson remembers. “I know domestic violence is very closely linked to poverty and so I know it happens in many, many communities where coffee is sourced but to have it brought out so directly and so publicly was really heartbreaking. So the fact that domestic violence is part of this equation…and also, too, in Indonesia, what really stood out was it was almost as if the men didn’t even know that the women were doing work in coffee. It was as if they didn’t exist. So here they are contributing so much and it’s just as if it’s nothing, not valued, and it didn’t even occur to the men that they are doing work.”

On a more positive note, Easson says, “One of the most powerful experiences that I’ve had in looking at this issue is being with a group of men in Nicaragua who were saying ‘yeah, it was hard for me to want to change but then I saw why it was important for myself and then I decided to stand up and actually talk to my peers.’ So when it starts to become more of the norm, like ‘hey man, you should invite your wife to the training!’—then it starts to become the favorable kind of peer pressure where the men are actually all part of helping to foster this change because they see benefits to themselves in terms of better income overall for the family.”

So, where do we go from here?

First, read the report. If you’d like more information, sign up for one of the webinars that Easson hosts. Become a member. Keep up to date with stage two and three developments (remember—this is only the completion of stage one!) of the Partnership for Gender Equity’s initiative by signing up for the Gender in Coffee newsletter. Keep an eye out for CQI and Partnership talks at SCAA as well as gender and coffee talks by other longstanding gender equity promoters such as the International Women’s Coffee Alliance or Sustainable Harvest. Stay informed. Have open discussions. Start to reevaluate practices that are already in place.

“What I’m hoping is that more people just start to ask more questions—start being more active about pushing some of these issues forward,” says Anunu. Ask questions. Push forward.

Rachel Grozanick is a freelance journalist based in Portland, Oregon. Grozanick has contributed previously to Bitch Magazine, 90.5 WESA in Pittsburgh, and 90.7 KBOO in Portland. Read more Rachel Grozanick on Sprudge.

All photos courtesy of Colleen Anunu.