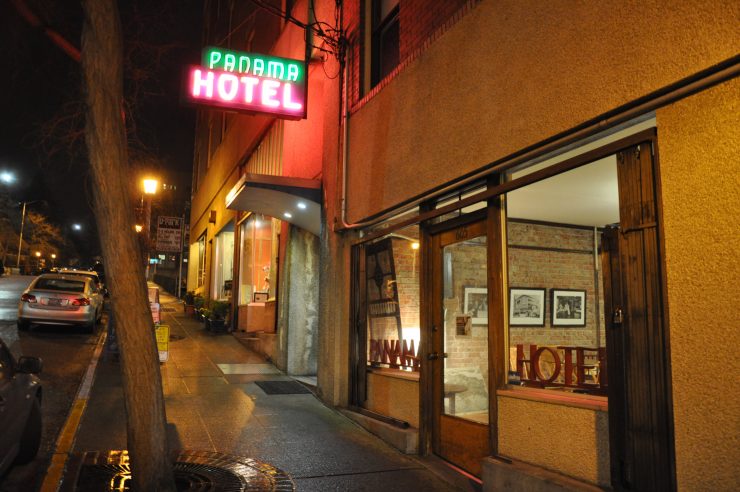

Step into the Historic Panama Hotel Tea & Coffee House and you’ll take a journey through Japanese-American history. Located in Seattle’s historic International District, a short jaunt from downtown tourist attractions and sports stadiums, the Panama Hotel and its namesake cafe are reminders of love and loss in a time of war.

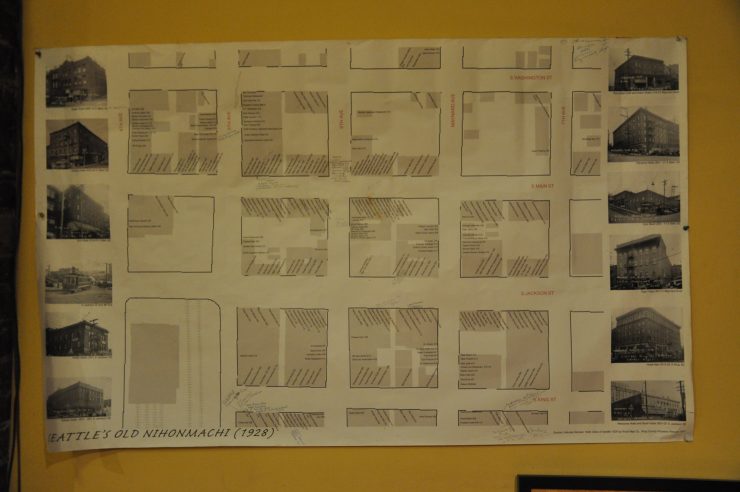

Built in 1910 by Japanese architect Sabro Ozasa, the hotel and its cafe were designed to be a community gathering place in Seattle’s old Nihonmachi (Japantown). The hotel remains fully functional, but what is most notable about the space is a window in the cafe floor that offers a glimpse into the past. From here, while waiting on a latte or herbal tea, visitors can view unclaimed personal effects and valuables stored by locals before they were escorted to internment camps.

In 1942, in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor, a United States executive order relocated Japanese residents, regardless of citizenship, to camps. Locals turned to the Panama Hotel for a secure place to hide their personal belongings.

Willow Hasbrook, the cafe’s only full-time barista, says area residents “hid their things down here so the people sending them to the internment camps couldn’t sell them or keep them.” Some of them never returned to the area. “Either the owner had passed away or their business was taken over,” says Hasbrook, “or they felt very unhappy with the American government and left without ever coming back to take their things.”

Tours of the hotel are available by appointment, but “no one can go into that room,” says Hasbrook, as a means to preserve what history remains. Jan Johnson, the building’s owner, received a preservation grant from the National Park Service to ensure this piece of Seattle history stays intact. In 2006, the Panama Hotel was designated a National Historic Landmark and, in 2015, the space was designated a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Views from the cafe floor reveal dust-covered wooden crates, abandoned clothing, stacks of books, and furniture. Further down, in the basement, is the only remaining Japanese bathhouse (“sento”) in the country. It served Seattle’s Japanese community until 1950, though it is preserved and group tours are available for a fee.

Throughout the cafe is a gallery of historic photos and additional collectibles, though it seems most people who walk through the wooden door are regulars, and Hasbrook knows them by name.

“We get [more] tea requests,” Hasbrook admits. Lavazza is the house coffee at Panama, but the impressive display of tea varieties is clearly the focus here. “Of what we have right now, my favorite is the Golden Chamomile Blossom—literally chamomile blossoms without anything added. It’s delicious…it’s very smooth and has a hint of sweetness.” Hasbrook definitely has a sweet tooth: “I’m a pastry chef by trade,” she says, noting her degree in baking and pastry arts from Johnson & Wales University.

From sweet to earthy, Panama serves Rishi Tea in black, white, green, and oolong varieties, while the coffee menu is comparatively straightforward: drip is served only until midafternoon, but espresso beverages are available until closing at night. Complementing the beverage menu is an assortment of pastries from local vendors (Hasbrook notes the hotel “wasn’t designed with a kitchen”).

What the building lacks in modern perks, it makes up for in charm. Wooden floors creak under foot, and exposed brick walls add to the ambience of this quiet retreat in the city. Free Wi-Fi (okay, there’s a modern perk) encourages guests to lounge at length in wicker chairs plumped up with decorative cushions. Occasional jazz performances bring people together in the evenings.

Even passersby can get a glimpse of the Panama’s importance to the community thanks to the hotel’s storefront window display on the corner of Main and Sixth. Aging photographs of the bathhouse, hotel rooms, and storage vault hang from the ceiling, while additional crates and memorabilia are encased for public viewing. “I believe these are some of the things that were left behind,” says Hasbrook, as we examine the artifacts in one window. Another window displays documentation of the hotel’s history and status as a landmark.

The cultural significance of the Panama Hotel Tea & Coffee House has not gone unnoticed. It’s a central setting in the 2009 bestselling historical novel Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, written by Jamie Ford. Now a documentary film is in production, with owner Jan Johnson working alongside producers Big Story Group to bring the Panama’s history to audiences worldwide. A preview of the film The Panama Hotel Story: Preserving the Panama Hotel Legacy is available here.

Johnson bought the building in the mid-’80s and has worked to preserve this piece of Japanese-American history for the Seattle community and beyond. A grant from the National Park Service has helped ensure the Panama Hotel remains intact and open for public appreciation—important work, considering it’s Seattle’s only official National Treasure.

Lori A. May is an author, poet, editor, and writing instructor based in the Pacific Northwest. A Pushcart Prize nominee, May’s work has appeared in the Atlantic, Writer’s Digest, Los Angeles Review, Midwestern Gothic, and many more. This is Lori May’s first feature for Sprudge.