James Hoffmann won the 2007 World Barista Championship in Tokyo, but at this point the accomplishment feels a bit in the rear view mirror. In the intervening years Hoffmann has helped establish Square Mile Coffee Roasters (which he co-owns) as a pioneer in the UK coffee scene; traveled the world for educational and promotional events with brands like Nuova Simonelli and World Coffee Events; kept up regular publishing duties at his popular personal blog; and lent his help to various efforts like the newly-formed Barista Guild Of Europe. Amidst this heavy calendar Hoffmann someone managed to find time to author a book titled The World Atlas of Coffee, which brings together a vast array of information on coffee production, preparation, and appreciation all over the globe.

To learn more about the story behind this project, we chatted with Mr. Hoffmann via email. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

How did the World Atlas project come about? Did Octopus Books approach you, or was this a concept that you looked for a publisher for?

I knew about them as they were the publishers of The World Atlas of Wine and a number of other great food books and atlases, so I was extremely interested in talking to them.

Ironically I’d tried to pitch a “World Atlas of Coffee” concept about a year earlier through my literary agents to some other publishers, but there was no perceived demand. I’d dabbled with writing it anyway, and self-publishing. This meant that when I agreed to write the book I’d already written several thousand words! However, all ended up having to be rewritten once I really started grappling with the project.

What were your goals with the project? Do any particular chapters stand out to you?

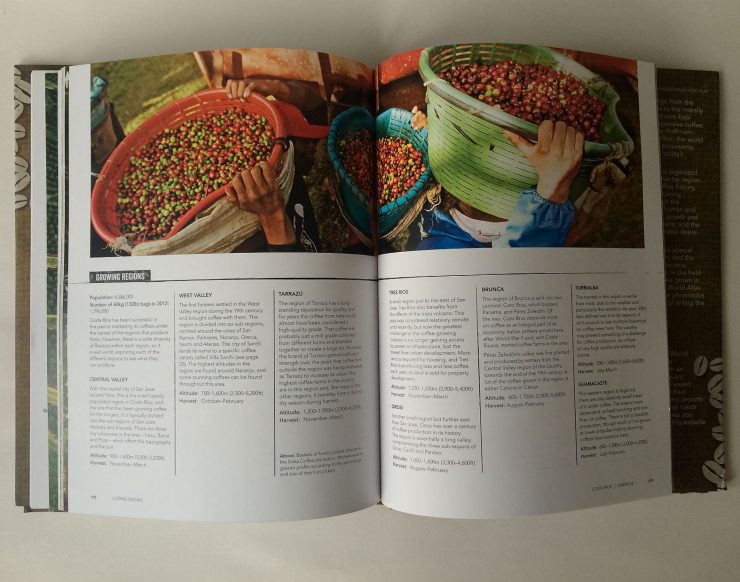

The goal of the book was to try to fill a big gap in our industry. For a long time, from a year or so into my coffee career, I’d been frustrated at the lack of resources if you wanted to know more about where a coffee came from, where a region was or why coffees seemed to come from single estates while others came from cooperatives or mills.

Speciality coffee has been incredibly successful but the push for traceability and transparency has made coffee somewhat complicated. It’s intimidating to try to understand all the words that now appear on a bag of coffee at your local cafe. Understanding that a coffee came from Kenya isn’t as challenging as understanding what or where a coffee from Kiawamururu is from, or who produced it.

Coffee is wonderful, but it can be very confusing and noisy and I hope to help make some sense of the noise for people and make coffee a little clearer. I hope the book also compliments all the stories we hear from roasters and buyers, giving a baseline of understanding about a producing country so people better understand why a single variety lot from Ethiopia is exciting and interesting.

I’m talking a lot, but my goal is probably similar to many other peoples’: I want consumers to enjoy coffee more. Be it brewing it better, buying it better or just understanding it a little more–it all contributes to making coffee a more delightful part of our lives.

There’s tons of in-depth knowledge condensed into this book, on a wide array of topics. What was the process like of gathering that knowledge? What sorts of sources were you looking for?

Gathering the data was hugely frustrating. I naively thought that the exporting groups in many producing countries would offer a little more assistance in terms of maps and data. It took a long time, because I wanted to do my best in terms of accuracy of facts and data—and this is incredibly tough. I ended up hiring someone to help me with research as it was too much to do alone.

I wish I had been able to travel extensively to research the book, but it just wasn’t viable with the budget I had. My priority was that I get the right information, and I felt that didn’t mean taking dozens of flights, spending weeks on the road, and investing a lot of resources. Nevertheless—I still wish I could have travelled to more of the places covered in the book.

I’m also grateful to the International Coffee Organisation, for giving me free access to their extensive library and helping with contacts and information.

What were some of the hardest parts of the Atlas to research and write?

Countries like Bolivia were very tough. There’s really no coffee organisation on the ground there, no accurate mapping and in the end I decided I wasn’t comfortable with any of the mapping for coffee in the country, which is why [the Atlas] doesn’t have a detailed one. I hated the idea that my map could end up defining the area that grew coffee, rather than describing it, but seeing the way information echoes around and repeats it felt like a real concern.

You’re one half of Square Mile Coffee Roasters in London—how has that experience with the sourcing and roasting of coffees informed the content of the atlas?

I don’t source or roast at SQM, this would be a more pertinent question for Anette [Moldvaer, Square Mile’s green buyer and director].

What was the process like of writing all this, fitting it in around a busy travel schedule?

Probably the biggest mistake I made is not understanding that writing is a job. It is work and it takes time. (I am sure this doesn’t need explaining to anyone at Sprudge!) I took on another job while already having at least one full time job, and it nearly killed me. Writing is best done when you aren’t exhausted, stressed and trying to do dozens of things at once. If I ever write another book I will take a few months off and do nothing else!

How have you found the reception of the book to have been so far?

Honestly, I’m both delighted and relieved at the way the book has been received so far. Instagram and Twitter have been great for seeing people’s photos and hearing their thoughts, and I feel relieved that people seem to be finding the book to be approachable and readable, which I really strove for. I just found out that the second printing run in the UK just sold through, and that the US is also printing a third run. This is beyond anything the publishers and I were expecting, so I’m obviously very pleased.