On January 30th, 2018 the new book from noted author, novelist, and McSweeney’s founder Dave Eggers will be released through Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House. Titled The Monk of Mokha, it’s 300+ pages that tell the story of Mokhtar Alkhanshali, Yemeni-American coffee professional and founder of the coffee company Port of Mokha. The book chronicles his journey from working in an apartment lobby in San Francisco to becoming one of his generation’s most important coffee professionals, braving war and personal hardship to help redefine the coffees of Yemen to a new generation of coffee lovers.

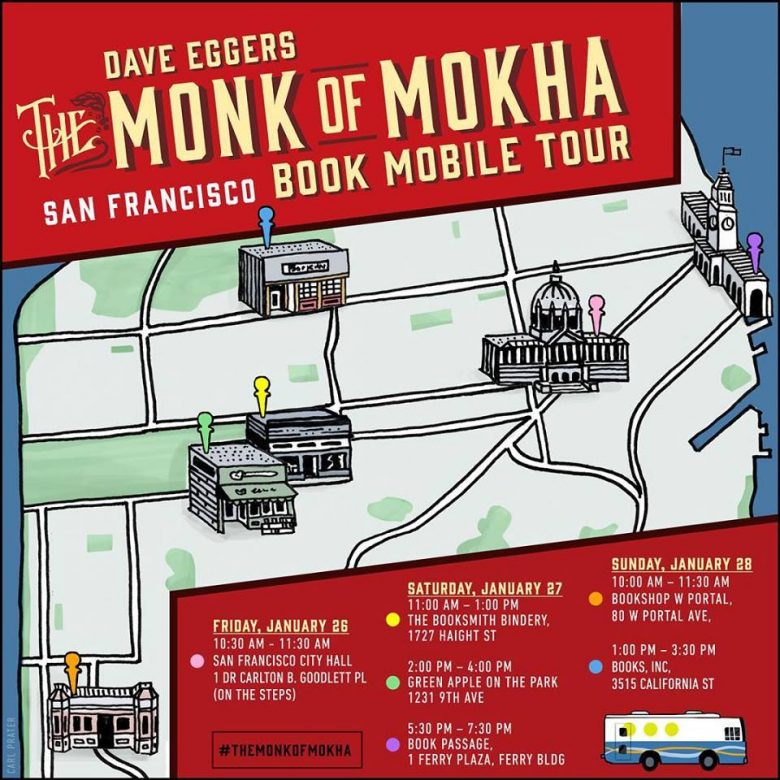

The reviews are in and they’re sterling. As with any new Eggers work, Monk of Mokha has been featured this week in publications ranging from The New York Times to The Guardian to the Los Angeles Times, who calls Monk of Mokha “a Horatio Alger story for the 21st century.” A flotilla of events are scheduled for the book’s release, starting tonight in San Francisco, where Eggers and Alkhanshali are appearing at the Nourse Theater as part of the City Arts lecture series. The fun continues across the Bay Area during the Monk of Mokha mobile book tour, in partnership with the San Francisco Public Library system, who have loaned out a bookmobile (converted into the “Mokha mobile”) for events across the region.

From there a speaking tour with Eggers and Alkhanshali is scheduled to tour across the United States, with appearances in Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, California, Washington, Michigan, and in Texas at the 2018 SXSW festival, in a talk hosted by Sprudge co-founder Jordan Michelman.

In advance of that talk, Michelman sat down with Eggers and Alkhanshali to learn more about the book, the exhaustive research process behind it, and how he used Mokhtar’s own social media to aid in reporting out this incredible story. This is the most high profile book written about coffee this century—maybe ever—and Eggers is unquestionably the best-known author ever to tackle the subject. He brings an outsider’s clarity to the daily machinations of the coffee trade, calling it “quite possibly the most complex journey from farm to consumption of any foodstuff known to humankind,” in a book filled with moments of sadness, laughter, danger, and triumph. Readers who want to drink along with the adventure can purchase coffee direct via the Port of Mokha website, where a new “Mokha Monthly” subscription service has been launched in conjunction with the book release.

Jordan Michelman spoke with Dave Eggers and Mokhtar Alkhanshali by phone from the San Francisco Bay Area.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jordan Michelman: Hello Dave Eggers, it’s a pleasure to meet you, and hello Mokhtar, it’s a pleasure to speak with you again. By way of starting, since this is how the book starts, Mr. Eggers—why did you choose that particular Saul Bellow quote to begin the book?

Dave Eggers: Oh, that’s my favorite book, probably. I re-read Herzog every year and that’s one of my favorite passages from my favorite book and I think that there’s something all-encompassing and yearning and big-hearted about that quote. It takes in all of the world and all its desires and ambitions and the political and the personal, all in one paragraph, and it just reminded me of the scope of Mokhtar’s ambition and his worldview. For an epigraph, we needed something big to mirror the enormity of Mokhtar’s vision and place in the world and what he achieved. It seems to, even though it’s not a quote about coffee or San Francisco or Yemen, but it seemed to have a nice parallel in spirit to Mokhtar’s story.

Michelman: Is that something you had in mind over the years re-reading the book? Or was it something that came to you fresh as you were trying to think of what to put as an opening quote?

Eggers: It was re-reading the book while working on Mokhtar’s book and when I came across that paragraph it just rang a bell. It just sometimes, something just hits you in the face. That’s the right thing. And it’s purely on a gut level and I put it in and lived with it for the last year sort of feeling like it’s the right thing. Readers seemed to respond, my early readers, to it and feeling like it had a commonality with the spirit of Mokhtar’s life.

Michelman: You mentioned early readers—I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of the book to prep for our interview today, and while I don’t want to rehash too much of what’s in it or spoil the fun for people once they get a copy, I was wondering if, Mr. Eggers, you could tell us how you first came to be interested in telling this story?

Eggers: We had met from years before. We had a mutual friend in Wajahat Ali, a writer and commentator. Wajahat and I had worked on an HBO pilot about a Yemeni-American police detective in San Francisco, and as part of our research, we met Mokhtar and he provided insight about what it was like to grow up as a Yemeni-American man in the Bay area. We got to know him that way and then a few years later Wajahat wrote to me one day, saying, “Did you hear what happened to Mokhtar in Yemen?” And Mokhtar and I got together a few days later and began to talk. At first, it was just a casual couple hours talk at Blue Bottle in Oakland and without any goals or parameters and just sort of a talk to see, out of curiosity.`

And then it slowly, very slowly, grew out of that. We just kept getting together—we would do a little cupping and educational work, watch some roasting…this was out at Boot Coffee in San Rafael. I would sit in on some of the educational sessions there and then afterwards we would hang out in the back of Willem Boot’s house and talk more about Mokhtar’s recent time in Yemen. We just sort of went backwards from there. It started with interviews about his most recent escape and the few months that led up to it and then we just kept working backward and backward and backward all the way into childhood and earlier visits to Yemen. So it was a long and meandering process without a clear goal until a little bit of the way in when we realized that there really was a telling book in Mokhtar’s story.

Michelman: How many total hours of interviews did you conduct for this book?

Eggers: I don’t know. I guess in my mind it would be 100, 120 hours, or something like that. That would be recorded hours, and that’s different than the countless amount of time that we spent just together and traveling and driving and visiting family and going to Djibouti and Ethiopia and Yemen and Santa Barbara and the Central Valley and visiting friends in the Tenderloin and family in Oakland and, you know. Over three years, it ends up really adding up and I think that there’s always two tracks for me as a writer/journalist. The on-record, recording, tape recorder between us times and then there are the in-between times where we’re just together and absorbing sometimes the atmosphere of a place like Boot or walking Mokhtar’s old neighborhood in the Tenderloin.

Almost always when we were together, I had my tape recorder there so a number of times when I would just turn it on when he was telling a story that I thought would be interesting. It wasn’t part of an official interview and it hadn’t been prompted by a question I had written down, but suddenly we’d find ourselves in some very interesting and necessary territory and the tape recorder would come on.

I think to really do something like this right, it really does take quite a long time because you really don’t always know the questions you should ask until you get to know somebody pretty intimately. And even then, so many of the very most interesting and crucial parts of the story don’t come out of an interview session. They come out of conversations and situations or being prompted by some place or memory that prompts another memory or a new story. A lot of that can only really happen over an open-ended long-term schedule.

Michelman: I’m curious, for fans of your previous work—is this book closer to something like Zeitoun, which is very much reported as non-fiction, or are there elements of the story that are dramatized as in your book What Is The What?

Eggers: It is not fiction. My training is as a journalist and my degree is in journalism and this is what I did for a living and continue to do for The Guardian in London and other venues. I’ve been reporting on the Trump Era, well, starting before he was elected and continuing. There’s a piece I have to turn in in the next few days about the wall between San Diego and Mexico and how it affects the DACA recipients.

Because Mokhtar was such an incredibly detail-oriented and attentive interviewee and because the vast majority of the events depicted in the book had happened in the months before we met and began interviews, it was [reported as non-fiction]. All of the larger political context, whether it was a bombing in Ibb, or whether it was a Houthi take over of Sa’dah, all of these other corollary political events took place parallel to his work.

All of these are part of the historical record. And so between the recentness of all the events and the incredible volume of other reporting done, it was relatively easy to confirm the veracity of all the events, the timing. And because Mokhtar is such an active documenter of his life, whether via Facebook, email, or WhatsApp, we were able to find and use countless pages and photos and entries—really everything from social media—and get events down to the minute in many cases. I was lucky to work with a really incredible amount of source material and ways to confirm all of the timings and dates and events to take.

Michelman: Mokhtar, I’m curious to ask you once you knew that Dave had come on to the project and that it was happening, did you have to keep it quiet or were able to talk about it with other people in your life? Were you able to tell people, you know, “Hey—Dave Eggers and I are hanging out and he’s writing a book about me.”

Mokhtar Alkhanshali: I mean, actually when the news finally came out, I felt bad because there were a few people I could only tell this to recently. And so I didn’t tell anybody, I just kept it quiet. I’ll give you an example. There was a Q course that Jodi [Wieser, of Gather Coffee Company] was taking at Boot. Dave was at that Q course with me, hanging out in the back, and Jodi had no idea he was there the whole time. She never knew until months later. She came to me and said, “Oh my God, I can’t believe I just found out Dave Eggers wrote a book about you.” And I’m like, “Gee, remember that time you were taking the Q course, that guy in the back taking notes?”

She’s like, “Yeah.”

“That was Dave Eggers.”

She said, “Shut up.” [laughs] But in terms of telling people, I just didn’t, really. For me I had a lot of things to work on—myself, my company—and I just didn’t want to add to anything else besides that. Dave and I thought it would be best that way. Just keep things super quiet, especially as a journalist and a writer, be able to do things more effectively and it was that way for a long time.

Eggers: It’s important for me to always be as invisible as I possibly can. We had an understanding from the beginning that I would sort of, in many cases, follow him around without it being known that there might a book at the end of it. The last thing that’s useful is for me is sort of walk straight into the door and announce to everybody that I’m going to be writing about their company or whatever it is. There were so many hours I spent at Boot and Blue Bottle and other places where I was just observing, sort of soaking things in.

Michelman: Mokhtar, for a non-fiction biography like this for which you are the subject, there are very real people in this book. There’s your family, there’s former employers, and there’s even a pretty prominently featured old girlfriend. Have you gone back now and been like, “Hi, you’re in this book about me”—how do you have that conversation with people? What is that like?

Alkhanshali: I was really lucky that Dave was the one writing this book. He is just incredibly great at making sure everybody involved is comfortable, and he’s been through this a lot. So, for instance, Miriam, my ex-girlfriend—we’re still great friends—he interviewed her and she knew what was happening. All the people in the book that I mentioned that way, they have all been a part of it, interviewed by Dave and they had the option to like, change their name, and things like that. So it was important to myself also that this book was not just my story. It’s a story about a lot of different people, about the Yemeni community, Yemeni scholars, and different people from the coffee community in Yemen. Making sure that it was an accurate portrayal was really important to both Dave and I. That was the case for the book and through the whole process.

Eggers: Yeah, there’s no one depicted in the book and by name that was surprised to be depicted. I observed a thorough process of making sure everybody is aware and making sure that it’s accurate from, not just Mokhtar’s point of view, but from their point of view, too. And so that’s sort of the luxury of having so much time to do it is to make sure you can very soberly go through every word and make sure that every place where Miriam was mentioned, it’s accurate, so that she doesn’t wake up one day and is surprised to find herself in a book and feel like it wasn’t the way she remembers.

Michelman: Dave, you talk about yourself, at the start of the book, you describe yourself as a coffee skeptic. And I’m curious to ask you now, what’s changed about that? How has the process of writing this book changed how you feel about the wider take on coffee?

Dave Eggers: Well, I mean, I think I go through life skeptical about a lot of things. I’m a slow adopter when it comes to many things, especially things that, from a distance, seem trendy, for trendiness’ sake, I guess. So I’ve been in San Francisco 25 years and coming from Chicago, you come in with a cynic’s eye, whether it’s about yoga or legalized marijuana or coffee or nude beaches. It all seemed very exotic, very radical in a way and I’ve grown to adopt everything, one by one. I grew to really appreciate the merits of yoga, for example, and I very much appreciate the slow food movement as I got to know it through publishing Lucky Peach. I got to know so many great food pioneers here through that, and publishing a lot of great food books through McSweeney’s and becoming more and more familiar with where our food comes from.

You know, in the Bay Area, you can’t help but absorb knowledge. There’s so much awareness and so many enlightened people, and when it comes to food, so many great places to buy and experience it, and restaurants where you can trust that the food’s been responsibly sourced. We are blessed by being surrounded by very enlightened food culture that you don’t have to do all the work yourself. And for somebody like me, who is inherently lazy about this—I don’t have necessarily all the time I want to do every bit of food research every day that I would like to—there are so many great, I don’t know what to call them, go-betweens, whether it’s your grocery store that you can trust that they have done the work and research for you or whether it’s a coffee shop that’s done the work for you.

And so it’s a long way of saying that I approach coffee the same way that I think the vast majority of people did even 20 years ago thinking, my God, even I remember when I got to San Francisco and when I saw $1.75 for a cup of coffee or a latte, that just seemed extravagant and ludicrous. But slowly and surely, just as we realized we pay too little for most of our clothing and we pay too little for much of our food and we pay too little for a lot of goods that we buy, somebody along the supply chain is not being adequately compensated and corners are being cut.

And so it’s the same way with coffee. And I’ve known this, intellectually, for many years about coffee, too, it’s just that what I really didn’t know was the level. I think it was the first day when we met at Blue Bottle that we popped in on a cupping and seeing that, and doing it at Boot Coffee many times, it was a whole other level. And even then the cupping aspect kicks in another skeptical impulse in me that says, oh my gosh, do we really have to go to this level of expertise and discernment when it comes to coffee? And the answer is yes.

The way that Willem and Jodi and Mokhtar articulate the importance of cupping, the importance of the farmers who make the coffee having the same set of standards for those that are roasting and consuming, and how important that is to improving the prices paid and the lives of the farmers that are picking the crop, it was absolutely mind-blowing for me.

At a distance, a lot of people will look at this and see a level of erudition or pretentiousness, but if you really understand why this is all happening, and why there are cuppings and scorings and why people are using the vocabulary they are to describe certain varietals, it all comes back to actually caring about the farmers who are creating what’s in your cup. And I think … That’s what I was trying to get across in so much of the book, is coming at it from a skeptic’s point of view and a generalist’s point of view, I think I had a good position to explain it to other skeptics and other generalists and make it believable and credible, and maybe even convert a few people to understanding just how important it is to know the story behind how it all comes to your local café and into your cup.

That’s a very long answer. Sorry, Jordan.

Michelman: No worries. I wanted to ask about a specific line in the text—there’s this great beat in the book that I circled in my copy, where you’re talking about Mokhtar and Willem Boot traveling together in Yemen. The line reads:

“When Mokhtar and Willem met in the hotel lobby, something subtle shifted in their relationships. Willem was his teacher, but now Willem was in Yemen. He needed Mokhtar as much as Mokhtar needed him.”

And I wanted to ask you, Dave, did you ever feel like that as well, telling the story? Did you ever have your own moment, maybe traveling in Yemen or just in general where you had that same thought to yourself as an author, as a journalist?

Eggers: Well, I was never in a position of expertise like Willem had been so for me, the power, the knowledge balance was always that way, where I was always the student and Mokhtar was always the teacher. For Willem, being this world-renowned expert who had traveled the world and judged competitions and taught coffee cultivation and roasting and cupping for so many years, I think that was a new thing for him, to suddenly be on unfamiliar ground where Mokhtar had to be his guide and the noble expert. But for me, I was always learning. I was starting from scratch. I started from that place and I’m still in that place.

Michelman: There’s all these different ways to unpack with story. It’s an immigrant culture in America story, and it’s also a really interesting class and money narrative—money serves as a kind of constant constraint throughout the book. But I’m curious if you thought of it at all generationally. Do you think of this as a millennial story?

Eggers: No, I don’t think it’s unique to Mokhtar’s generation at all. I think it’s a timeless story of the entrepreneurial zeal of somebody from an immigrant family. It’s the story of this country. It’s never been different. It’s always been the same. Repeated every day in every city and every period. Our economy and the lifeblood of the nation is driven by the unfettered inspiration of young entrepreneurs, many of whom, an astonishingly high proportion of whom have ties to other countries and might be first or second generation immigrants and who are seizing the American dream with both hands.

But I do think that Mokhtar embodies that in a millennial way, interprets it or brings a millennial cast to it. Bones of Mokhtar’s story are the same as so many stories throughout the last 200 years. It’s the same story of seeing the American dream and reinventing oneself to seize it. But I don’t know if you disagree, Mokhtar, if you think of it as a uniquely contemporary, millennial story.

Alkhanshali: That’s an interesting question. You know, it’s strange for me to see my name and the term “American dream,” describing my journey that way, so it’s hard for me to say. I will say that, yeah, that story that my grandparents heard when they came to this country—and my parents too, with their limited resource—well, we all hear stories of immigrants and what they were able to accomplish here. But it seems like that for my generation, as millennials, that upward mobility and opportunity has become very difficult to realize.

Eggers: Yes.

Alkhanshali: When I was growing up my ambition was just to get a job as a bus driver, so I could have health benefits. But I always read a lot of books, and always had this thing in the back of my head, this fantasy world I lived in. In many ways I probably fueled a lot of my ambition and then, it’s hard for me not to believe in this dream when I see where I am today. And I can talk to young people who maybe feel trapped in the system, in a box, and I was there, too. We do face difficulties, and there are systems that might be against you, but it doesn’t mean you can just give up. Maybe you don’t have to cross an ocean on a boat like me, but it’s universal.

Michelman: That makes sense, and it feeds back into ways in which class and money are constraints in the book. No spoilers, but at one point in the book, you’re trying to rent an apartment at a building you used to work in, and the person who is considering leasing it to you is attempting to figure out if you’re a Saudi prince, or if you have a ton of money, which you do not. And ultimately it’s your connection to coffee that impresses him enough to get the spot.

The narrative has to have that, you know? For it to be meaningful to get your dream apartment, you need to have been working there as a door guy in the first place. It wraps itself into the narrative.

Alkhanshali: That’s my trick. You know, “started from the bottom now I’m here.” While I lived there I couldn’t tell anyone because it was too fantastical. Who could believe I was a doorman there? I don’t even tell people. It’s hard to explain my life because it’s just strange. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to do this book. I’m not a Saudi prince. I am the opposite.

I think that in life, you have to experience bitter moments to be able to appreciate sweet moments and there were moments in my book that are really hilarious. There are moments that are really not funny at all, and I have a hard time talking about that. I have never mentioned those, especially if you read the last third of the book, the last hundred pages, really are just pretty intense, and it’s hard for me to speak about that.

Again, like for me, I know I could not have done this journey with anyone else. Dave is really just a very caring and passionate person and was very endearing and, you have to feel comfortable being verbal with him and I don’t think I could have done that with anyone else.

Michelman: Thank you both very much, and best of luck on the book tour.

Eggers: Thank you.

Alkhanshali: Thank you.

Jordan Michelman is a co-founder and editor at Sprudge Media Network. Read more Jordan Michelman on Sprudge.