“First you have a bite of cake, then you have some water, and THEN you drink the coffee.”

These are the words told to me by Giuseppe Schisano, owner of Don Café Street Art Coffee in the Italian city of Naples. Used to sipping my espresso from a tiny cup, I was surprised that the coffee I was about to drink—prepared in a traditional Neapolitan flip pot—came with so many steps.

A lifetime coffee lover, Schisano was inspired to open a mobile coffee cart after seeing one in Copenhagen. He wanted to do the same in the Quarter Spagnoli of Naples, where he was born and raised, but with a twist: he would use the flip pot, known in Italian as la caffettiera napoletana, or colloquially, la cuccuma or la cuccumella.

The origins of the pot can be traced to France, where percolators were patented in the early 1800s. When the design reached Naples, local artisans made it their own, producing versions that differed in shape, size, and material—the Neapolitan preference was for tin or aluminum, rather than France’s more expensive copper. It spread rapidly throughout the city, and at one point became synonymous with coffee culture in the city of Naples.

Requiring time, money, and patience, cuccuma-prepared coffee embodies hospitality. This notion of serving coffee as an act of care is still found in the city’s tradition of caffè sospeso, or suspended coffee, which allows customers to pay for an extra cup at certain bars, so someone who can’t afford to pay can still enjoy one. It also lives in the Neapolitan tradition of ’o cuonzolo, derived from the Italian consolare, to console, which consists of bringing foodstuffs to people who have suffered a loss. Schisano shared a vivid memory from his teen years of people bringing coffee and sugar to his family’s house when his father passed away, as part of that tradition. The scent of coffee on that day, he told me, left a mark on him.

Growing up in the Quartieri Spagnoli wasn’t easy, Schisano tells me. This neighborhood was once considered quite dangerous, and many who grew up here lacked job opportunities. Schisano found various positions in the food service industry, eventually moving to Germany for work. After his stint there, he took that inspiring trip to Copenhagen.

Schisano needed help to get the funding and permits he needed, but thanks to the support of two organizations (If-ImparareFare and Caritas), he was mentored in business and secured a loan for a bicycle-powered cart in 2018 to serve coffee to locals and visitors along Via Toledo, the main thoroughfare of the Quartieri.

In keeping with the local coffee-as-hospitality tradition, Schisano asks for donations only at his cart, where his younger brother, Manuele, also works. “Some people leave five or six euros, some people leave 20 cents, and they’re thanked in the same way,” Schisano told me.

The cart’s success allowed him to open a physical location in the Quartieri earlier this year, which serves food, drinks and, of course, coffee from una cuccuma. He hopes to expand his business further and plans to serve other types of coffee, and to launch an online shop where people can purchase his blend and their very own flip pot.

In 2019, Achille Munari, an Umbrian transplant to Naples, opened a cafe about a kilometer away from Schisano’s cart. Unlike Schisano, Munari was not particularly passionate about coffee throughout his life, but he was touched when his Neapolitan friends prepared it for him in a traditional flip pot for the first time. He was struck by the care that it took and the idea that it was to be sipped slowly, rather than consumed as a quick, energizing exclamation point after a meal. He even decided to name his cafe after it, and so the Cuccuma Caffè was born.

“Today, we have espresso in Italy, which is fast, whereas the old Neapolitan coffee is slow,” Munari tells me. We’re chatting together just after the end of a lunch shift (the cafe serves family-style platters of spaghetti and pastries). “It wasn’t just a way to take a break and have a pick-me-up, it was a way of spending time together. I didn’t want this tradition to be lost, so when people have time, they can come here and sit calmly, drink some water before having their coffee, talk, and relax. That’s Neapolitan coffee—conversation and spending time together.”

His dedication to the pot and tradition shines through in the cafe’s decor, which includes knickknacks and il Museo della Cuccuma (the Cuccuma Museum)—a collection of antique flip pots of differing shapes and sizes.

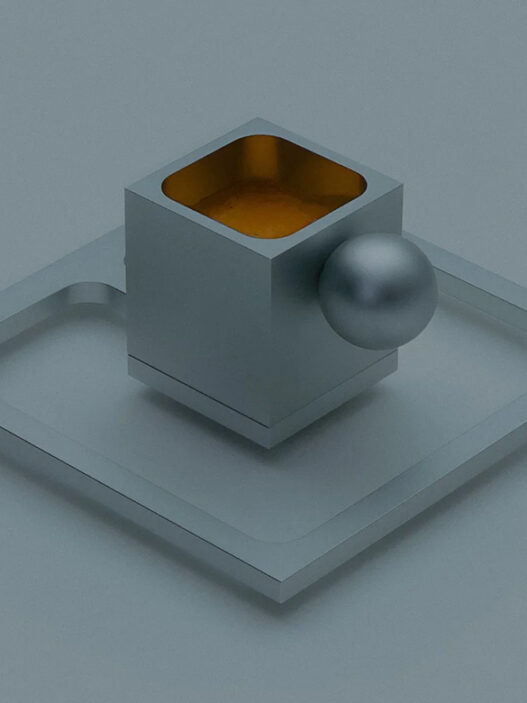

La cuccuma was eventually largely replaced in homes across Italy with Alfonso Bialetti’s faster Moka Express, patented in 1933. The two share some similarities. Like a moka, la cuccuma has three elements—a filter, a water chamber, and a pot with a spout, but unlike a moka, which counts on steam pressure to make coffee, la cuccuma relies on gravity.

Step one for making coffee in una cuccuma is filling the water chamber. Next, coffee is spooned into the filter. The filter is closed with a lid and then put into the water chamber. The pot is turned upside down and secured on top of the water chamber, which is then placed on the heat. When steam and droplets of water start to come out of the spout, the whole device is flipped over so that the water passes through the filter and the coffee drips into the pot. Traditionally, a paper cone, referred to as il cuppetiello, is put over the spout while waiting for gravity to do its job.

It is recommended that the coffee be drunk as is, despite the fact that many Neapolitans might take their their espresso with added sugar. Both Schisano and Munari explained that there’s no need for sugar when drinking una cuccuma because the gentler percolation process helps promote a smooth aftertaste. To illustrate, Schisano used a different example from Neapolitan cuisine. “It’s like how fried pizza and oven-baked pizza are made with the same dough, but cooked differently, which gives them a different taste.”

After the cake and water, I examined the coffee in its little glass. The brown foam and silky shine of espresso were absent. “Try it,” Schisano urged, “before it gets cold!” The coffee was mild, flavorful, and smooth, with absolutely no need for sugar. And perhaps most importantly, you can taste the connectivity and history, the hospitality and traditions of Naples, when drinking coffee made in this beautiful, complex Italian city’s local favorite brewing method. The important thing is to enjoy it as intended: slowly, and in good company.

Molly Fitzpatrick is a Rome-based writer and the creator of Luggage and Life. This is Molly Fitzpatrick’s first feature for Sprudge.