Ricky Duraes calls to say he’ll be right there. It’s a warm, sustainably bright morning, and I’m standing on the corner of Ferry and Madison streets in Newark, New Jersey. I can think of no one better than Duraes to talk about the Portuguese coffee scene in the Ironbound neighborhood. This immigrant community is one he became acquainted with 20 years ago, when he left Portugal for the United States, where he started a part-time journalism career. His beat was, and still is, the very neighborhood where I’m waiting for him to finesse the double-parking whims of the Garden State’s most populous city.

I’m meeting with Duraes as a follow-up to an earlier solo expedition to the Ironbound. On that visit, only traversing the district’s iconic Ferry Street, I had already seen a sweep of signs advertising Portuguese businesses, from jeweler to grocer, from travel agency to hardware store. When asked where to eat and drink like a local, the amicable staff at the LusoAmericano bookstore were slow to commit to a referral, implying no choice would be wrong. I decided on Teixeira’s, a well-Yelped bakery cafe. Under the wistful gaze of wheat harvesters on a panel of blue-painted tiles, I consumed what everyone else did: a bowl of caldo verde (kale soup, with or without chorizo), a slice of broa (cornbread), and a galão (a glass of one part espresso and three parts foamed milk). Dessert followed at Nova Alianca Bakery & Cafe. There I ordered a bica (espresso) and three pastéis de nata (custard tarts), though not only the classic version—based on a two-centuries-old recipe from the Monastery of Jerónimos in Belém, Lisbon—but also more unorthodox Nutella and lemon varieties.

And it is at Nova Alianca today, a Sunday, around 9:30 a.m., that Duraes and I are unable to find seats. Unfazed, my informant heads a short block east. At Pão da Terra, I sit at the single free table, while he queues to order his favorite drink. A meia de leite is similar to the galão, I learn, though it comes in a ceramic cup, with proportions reportedly closer to the “half-milk” its name denotes.

“Seventy percent of the customers in any one of those coffee shops, they are not even from Newark, but they come to Newark. Portuguese people, they come to the church,” Duraes explains, suggesting their next logical stop is a cafe.

“A melting pot,” he calls the Ironbound, where “everybody finds the right place to be, the right place to build their business.” The metaphor has a refreshing ring in the context of coffee, which would have been frequently served from a pot in the United States that welcomed Duraes.

“Right now, it’s three different ethnicities: Portuguese, Brazilian, and Ecuadorian. If you go back to the route of the three different countries, all have a strong connection with coffee,” he says.

According to Duraes, “coffee’s always present no matter what you’re doing, what time of the day.” He outlines a typical weekday’s waves of coffee shop clientele. It begins with construction workers, who at 6 a.m. come in need of a newspaper, a pack of cigarettes, and a cup of caffeine. It ends in the evening, with commuters making an after-office pit stop following a call warning there’s no more bread at home.

After our demitasses empty, Duraes, in journalist mode, is keen to back words with eye-witnessing. Before long, we are in his black Mercedes sedan, setting out on the culturally thickest 90 minutes I’ve experienced. We drive along Ferry Street, the quickly expanding Chestnut Street, and little streets in between. The radio plays pop. The rearview mirror dangles a Catholic devotional medal over a black ice-scented little tree air freshener.

On this route alone, we count over 30 bakery-cafe type establishments; the majority are Portuguese, though Brazil and Ecuador represent, too. We inspect the pastéis up close at Pão de Milho Bakery and Cafe Caffé. Upstairs from the latter, we drop in on SPT, the Portuguese TV station. Across the lot, we eyeball a port tasting room. From a distance, we see the Ironbound Stadium, which Duraes says was a major pull for so many soccer-playing Portuguese newcomers living in the vicinity. We skim the sprawling wholesale premises of both Viera’s Bakery and Teixeira’s Bakery, two players in the ongoing “big discussion [about] who is the oldest.”

At a jumbo-sized Seabra food store, rainbow upon rainbow of Portuguese imports and locally made products are inter-stocked with the usual US fare. More blue ceramic tiles hang in the seafood department, though these azulejos depict fisherman amidst seagulls, a lighthouse fixed in the distance. In the bakery department, a small, silver-haired deliveryman adroitly stocks Teixeira’s very own corner.

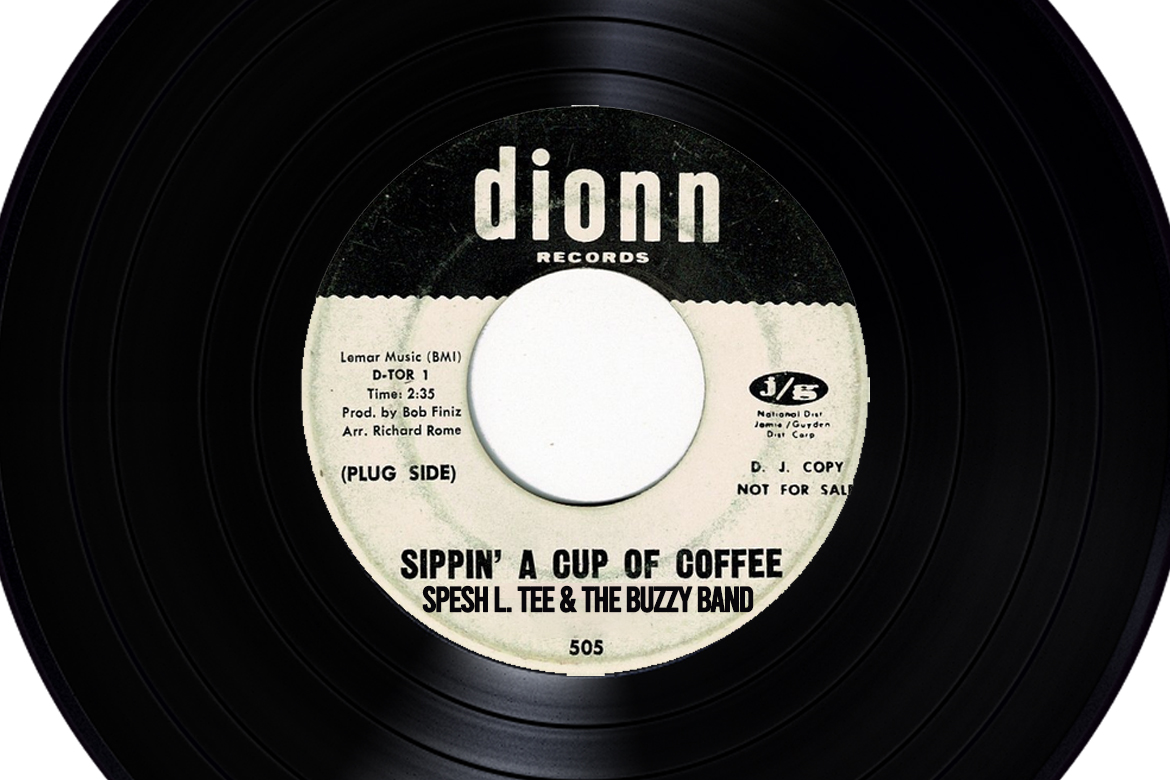

Throughout the tour, the array of coffees is conspicuous, advertised on brand-stamped sugar packets, ceramics, and plastic lawn chairs with matching sun umbrellas. There are major Portuguese coffee companies, such as Torrié, Caffècel, and Delta. There is the Newark-bred Socafé, which plays Frank Sinatra singing “The Coffee Song” when your call to them is put on hold.

Towards the end of our journey, we arrive at the Sport Club Português. The district has several cultural associations, but this is the oldest, established in 1921, when the Portuguese began arriving in Newark. Entering the gray breadbox of a building reveals another layer in the mille-feuille—or better, massa folhada—of Ironbound life. Trophies glimmer. Azulejos abound. Besides the petite bartender, it is mostly men. The younger ones watch TV, sitting at a long bar with as much surface area devoted to alcohol as to coffee preparation. The elders play cards in a backroom.

On our way out, Duraes runs into a friend, a 90-year-old artist who says he moved to Newark in 1946, after abandoning work on a ship in Portugal. In a soft, steady voice, he replies that he doesn’t drink coffee. He claims to have no secret to longevity, noting: “Our health depends on our responsibility, not God or anything else.”

With the 11:30 a.m. mass nigh, Duraes goes to join his wife and children around the corner at Our Lady of Fatima. He has eaten nothing during our time together, but I imagine he’ll follow the custom of post-prayer pastéis.

I return to one of our drive-by sightings, Alvaro’s Pastry Shop & Deli. A lull in customers encourages my ordering off-script. Aglow in the display glass fluorescence, a bean-filled pastel de feijão and a queque, a corn muffin-like cake with scalloped edges, call. But both taste more savory than sweet, unable to balance out the espresso I also request. Alvaro’s own pastel de nata is delicious, if not the Ironbound’s best.

Karina Hof is a freelance journalist based in Amsterdam. Read more Karina Hof on Sprudge.