Perhaps the most flummoxing part of coffee for non-professionals is how exactly a pour-over can taste so good when made at a cafe and so, so bad—so bad—when made at home. Am I not pouring correctly? Are my ratios wrong? Are they using sugar water? Do they keep all the good beans and sell me the junk to make me feel bad about myself? Because it’s working.

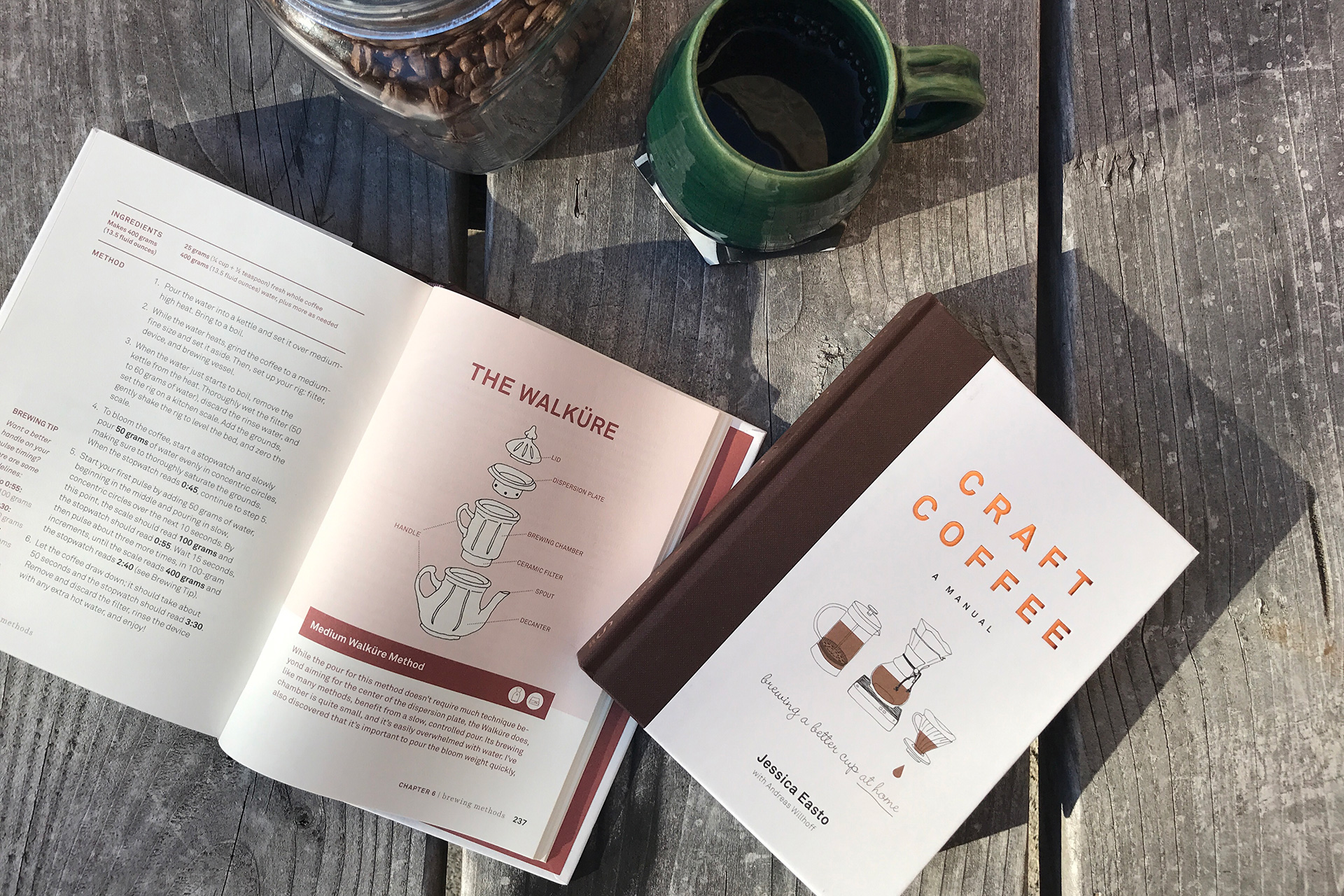

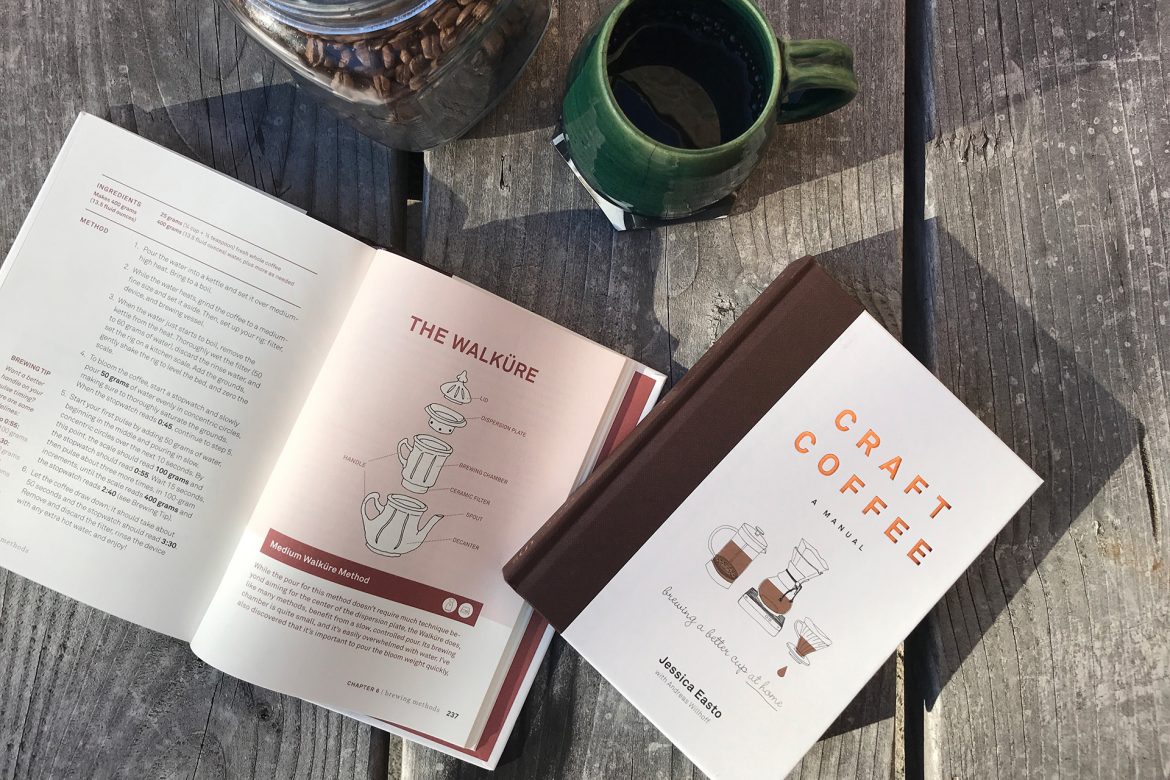

But there’s a new book looking to make you feel less bad about yourself by helping you, the home brewer, make better coffee. Craft Coffee: A Manual is a one-stop shop to improving your coffee across a number of brewing methods. Written by Jessica Easto—a book editor and “non-coffee person”—with the help of her husband Andreas Wilhoff of Chicago’s Halfwit Coffee, Craft Coffee is well-written and easy to understand, providing tips and recommendations for home users with varying degrees of interest in coffee. Whether you are looking to buy your first piece of coffee brewing equipment or have every gadget under the sun, this book has useful information on how to make better coffee. And more than just telling you what to do, Craft Coffee tells you why you’re doing it, providing the theories to back up the suggestions.

Coffee professionals will also find this book to be a worthwhile read. Even if none of the information is exactly new, it serves as a concise refresher course on all the moving parts that go into a properly brewed coffee. I know personally, I found myself being much more mindful and deliberate when making my morning Chemex, and the results were evident in the cup.

To learn more about the book, Sprudge sat down with author Jessica Easto (via electronic communiqué), where she tells us all about how a “non-coffee person” ended up writing a coffee book, describes her desert island coffee setup, and gets put on the spot to defend claims she made in her book about the siphon.

Hi Jessica. Thanks for taking the time to talk to us today. This book is written from the perspective of someone who isn’t a “coffee person,” meaning you aren’t in the coffee industry. So then, who are you and how did you come to get involved with coffee?

I don’t think I had one “a-ha” moment—I kind of stumbled into coffee. I didn’t know anything about it for a really long time—my parents never drank coffee or kept it in the house. Because of this, I (1) never thought to use cream and sugar when I started drinking it, and (2) did not know how to operate a coffee machine. Pathetic as that sounds, the former helped me quickly realize that some coffee tasted much better than others (not that I knew why), and the latter meant I bought a cone dripper on the internet because it seemed easier and more practical (not that I knew how to use it properly). So I did that for a few years, and then I met Andreas, who had been a barista, in grad school. He told me what I was doing was called “pour-over” and that there were cafes that specialized in it (I had no idea because I never lived anywhere [near] them). That was kind of the start of things.

Of course the catch-22 of it all is that now that the book is published, you are officially a coffee professional.

I suppose I’m now a professional coffee writer, which is pretty cool, but that’s a lot different than being in the thick of it. I’m still kind of orbiting.

But you had the help of a professional. What was Andreas’ role in the book?

He taught me a lot of stuff before I wrote the book, so that was crucial. There was also a lot of me asking him, “would a coffee professional agree with this?” As someone on the periphery, I noticed that there is often a communication gap between professionals and hobbyists (or customers) like me (one of the reasons I wrote the book), and that I approached some topics from a slightly different angle or perspective than a barista, for example, would. I had him read parts of it several times to make sure I wasn’t totally off base, and to make sure I could defend what I was saying in case someone challenged me (my worst nightmare). He also helped me develop the methods. We included some devices that we weren’t 100 percent familiar with, so he would test methods, then I would test and rewrite the methods, and then I had someone who was completely unfamiliar with coffee test the methods—so we had people coming at them from all skill levels.

There’s a lot of information and it’s well organized. How long have you been thinking about this idea and how long did it take for this book to come together?

I had been thinking about the idea of the book since 2014. I started writing it in earnest in 2016—I actually wrote it fairly quickly, most of it between August and December 2016. I already knew the topics I wanted to cover and the basic order I wanted to cover them in, so it was more just getting the info on the page and filling in the gaps in my research. And then the publishing process (editing, production, printing) took the next nine or so months. And here we are!

The book seems to meet a wide range of home brewers at their level. Who would you say this book is geared toward?

I certainly wrote it for home brewers. And the thing about home brewers is that they exist on a spectrum. They may all love coffee, but they don’t all love it the same. I’m not as fanatical as some, and many are not as fanatical as me. I noticed that some people have a hard line and they don’t want to cross it. They may give into a burr grinder, but they’d be damned if they are going to start measuring water in grams. So I wanted to show people that there are ways to optimize a cup, even within certain boundaries—cost, time, skill, etc.—and that’s fine. You brew you.

So is this a book a coffee person would get their parents or vice versa? Or is it both?

I think both. I tried to organize it in such a way that if you had some skills and wanted to go deeper, you could, or if you had zero skills and wanted to just skim the basics for now, you could. We’ve gotten a lot of great feedback from coffee people (baristas, roasters, etc.), saying there is something in there for everyone. I mean, I’m not sure it would teach a World Barista Champion anything, but Andreas says a barista at the beginning of their career or someone who works for a place without a training program would find it useful. Several coffee shops are selling the book and positioning it as a resource for their customers who want to know how to use their beans, and Andreas and I hope to get it into more shops in the future. It also looks mighty fine on a bookshelf.

In the book, you expressly use the term “craft coffee” as opposed to Third Wave or specialty. It’s been a vague term in the coffee lexicon but you give it a more rigid definition. How do you think that will help readers of the book that are new to this coffee world better understand what’s going on?

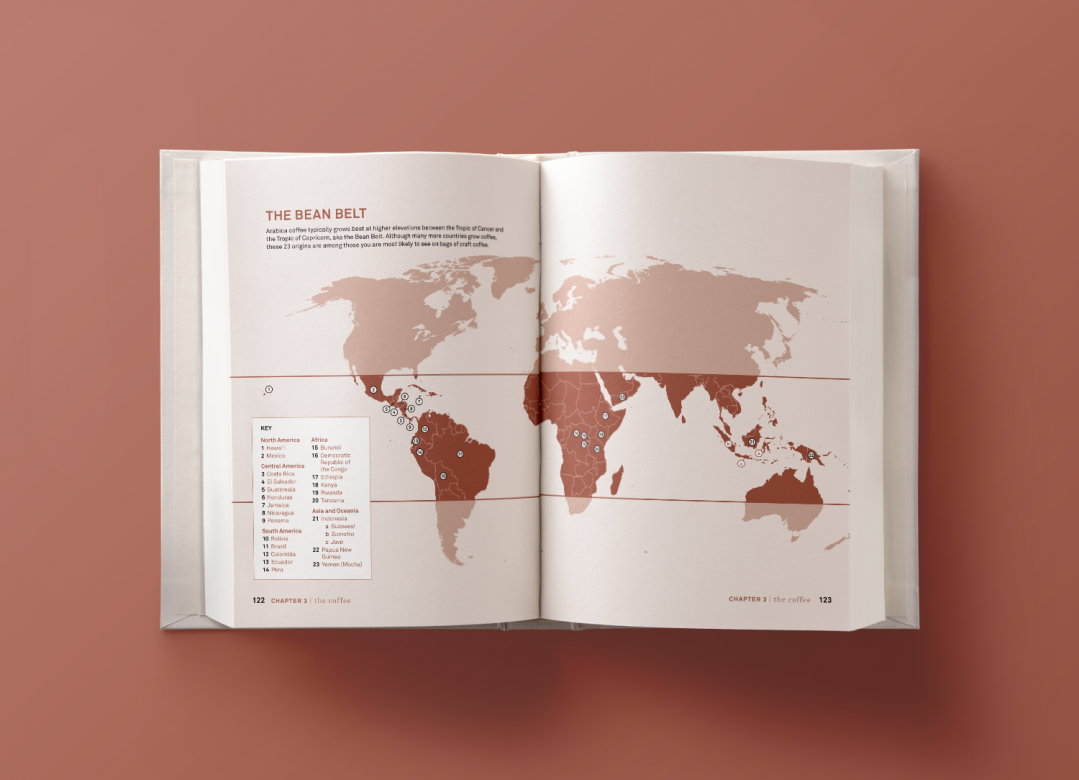

I think it’s important for people who want to understand coffee to know what separates “specialty coffee” from the rest of the coffee in the world, and then, under the specialty umbrella, how this smaller subset of “Third Wave” or “craft” coffee actually distinguishes itself. I mean, Starbucks is specialty coffee, but what they do is much different from what, for example, Ruby in Wisconsin or Onyx in Arkansas are doing. I also cannot stand the way the mainstream media talks about Third Wave coffee. It’s basically a punchline at this point, which is so, so unfortunate—it reinforces misconceptions and muddies the waters. Let’s just say there’s a lot of voices, and some of them are saying stupid—and flat-out wrong—things. I think the alternative name “craft coffee” (at least how I use it in the book) is less sullied and more accessible to readers because of the obvious parallels that can be drawn to craft beer. Craft beer is accepted and even practiced by a wide range of people, including my dad.

Let’s say a person has all the requisite equipment outlined in the book—including fresh coffee—what is the single piece of advice you can give someone that will have the greatest impact on improving their coffee making at home?

I would say: Start with one device and practice until you understand it inside and out, and remember that it takes a certain level of patience to perfect a cup to your liking. For someone like me, who doesn’t make and taste coffee full-time, it can take awhile to develop a palate, develop preferences, and thoroughly understand all the elements at play—and then there’s always something new to learn. I, for one, am still developing all my skills—maybe you never stop doing that. Make and make again, and taste and taste again!

This being about coffee brewing, there are going to be disagreements about something or other, so please indulge me. No one has ever been more wrong about anything in the history of opinions than when you say the siphon is a consistent brewing method that doesn’t require a lot of technique. Defend this indefensible claim.

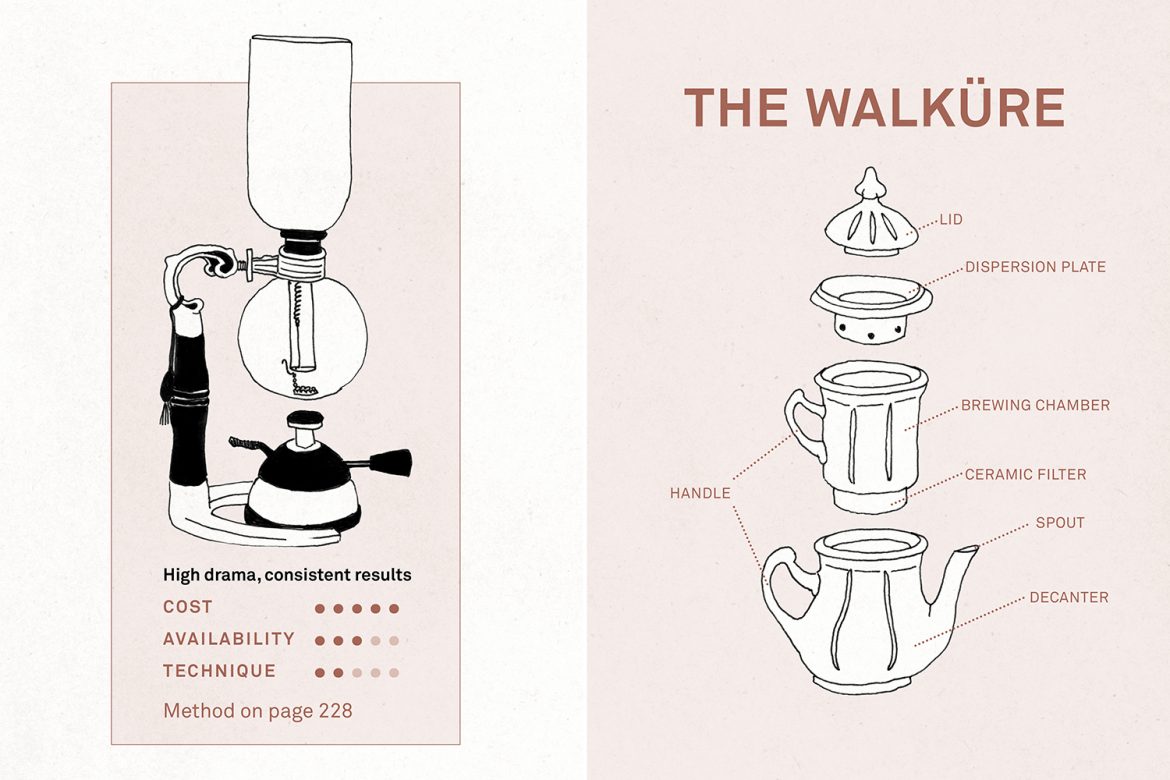

Uh oh! My worst nightmare! So… I think it’s a consistent and relatively low technique. The method we use in the book is adapted from a Blue Bottle recipe, and they, to understate it, know what they are doing. First, you don’t have to pour anything with any kind of control—I personally think timing any kind of pour (especially when you aren’t practicing over and over) is more difficult than the siphon method, in which you mostly just stand there. The steps of the siphon method are triggered by very clear checkpoints, like “is your water boiling?” and “does the thermometer read 202F?” You let the design of the device and physics do most of the work. It’s relatively passive! I guess taking care of the filter is sort of finicky and cleaning it up is kind of a pain. And its appearance and the open flame make it seem complicated. But none of that is part of the brewing method! Andreas and I recently had a nasty siphon brew from a lauded restaurant (who shall remain nameless), so maybe not all methods are great. But the one in our book is pretty good!

I don’t like it, but I’ll accept it. Ok, last question. You’re stranded on a desert island, and a box washes ashore marked “coffee”. What are your ideal contents of that box?

I’m going to pretend the desert island is in prime coffee-growing territory and there is some delicious, juicy, slightly fruity heirloom variety that I can somehow learn to roast perfectly over a campfire and that there is a natural spring of perfectly mineralized water for coffee making at my disposal. (What a life!) In that case, my (properly padded) COFFEE box would include (1) a solar-powered gram scale/calculator combo (I am bad at math), (2) a high-quality hand-crank burr grinder, (3) a Walküre Karlsbad brewer, and (4) a Kalita kettle. The Walküre is my favorite device because its design (which has been the same for generations) makes pour-over really user-friendly, and its crazy cross-hatch built-in filter gives you a surprisingly clean cup without the use of paper filters—a plus on a desert island. And I just really love the Kalita kettle.

Thanks Jessica.

Zac Cadwalader is the news editor at Sprudge Media Network and a staff writer based in Dallas. Read more Zac Cadwalader on Sprudge.

Photos courtesy of the author.