On Saturday, April 22nd at the 2017 SCA Global Coffee Expo in Seattle, a group of seven coffee professionals gathered for a public panel discussion on the topic of “Building Influence and Changing Power Structures.” The panel was led jointly by Michelle Johnson (founder, The Chocolate Barista) and Tracy Ging (co-founder, The Coffeewoman), and included Tymika Lawrence (Genuine Origin), Phyllis Johnson (BD Imports), Liz S. Dean (Irving Farm Coffee Roasters), Jenn Chen (Freelance Coffee Marketer), and Meister (Cafe Imports).

Over a thrilling (and far too short) hour and a half of panel discussion and Q&A, the event’s guests and moderators spoke to a packed room. The goal was to “further propel the conversation of intersectionality within the coffee industry at Expo” across a range of experiences and viewpoints.

There is no more powerful story than the panel itself, so below please find an abridged chronological transcript from the event—a full recording will be released in the coming weeks via the Coffeewoman Podcast.

The following has been slightly abridged from the live conversation.

Phyllis Johnson:

“Brown and black hands pick beans. White hands trade beans. Questions of intersectionality in coffee are global.”

Liz S. Dean

“Mixed race people don’t exist because we have great genes—we’re here just like anyone else, and we occupy a weird space racially in terms of intersectionality.”

Meister:

“When we get on the phone and customers hear my voice, the conversation changes, becauase they realize that I’m not a man. How do you do business effectively in an environment where you wonder if people treat you differently or talk to you differently if they ‘knew who you were’?”

Jenn Chen:

“I one had someone ask me, ‘Hey do you know this person in China last named Chen?’”

Tymika Lawrence:

“I’ve had people ask me if I ‘even like coffee’ in the middle of instructing a lab. Look around this room—how many black woman instructors do you see, how many black woman managers? If I didn’t like coffee, do you think I could even be here?

I’ve always had to reference my resume. People ask you to reach into your past and measure what I’ve done, and they don’t even realize it. I have to casually drop my resume into conversations as a way of saying I’m a qualified coffee professional. I’ve had to qualify myself in every new coffee space always.”

Michelle Johnson:

“I want to talk about biochemistry, coffee science, soil health—that shit’s cool! But there are blockades that come up. It’s like I’m the go-to now, and people want to only talk to me about blackness. I’m at this coffee expo and people only want to talk to me about one thing.”

Tymika Lawrence:

The burden of emotional work is exhausting, but you either do it and be successful or not. I think about what I could get done if people didn’t have to waste the time on that.

Phyllis Johnson:

Could you imagine coming to a table with your largest customer, and instead of being asked about your samples, or about coffee, the question is: “Do you think white people are smarter than black people?” And then there’s a pause, and they say, “No, I really need you to answer that.”

Tymika Lawrence:

I don’t think in general people think about proximity to whiteness, but people of color have to. It’s ingrained in us.

People of color in coffee have a lot of things in common, and typically it’s proximity to whiteness. Think hard about the people of color you know in coffee—they have a college degree, they speak in a way people are comfortable with, and they dress a certain way that is comfortable. I could not be someone like Cardi B and be where I am professionally. Proximity to whiteness is a barrier, and the expectations people have for women and people of color come back to this notion of ‘what’s right’—and it’s proximity to white normativity.

Meister:

Coffee is a global industry and the people of color that we interact with in ways that lift them up or give them empowerment, the people of color this industry treat as rockstars—they’re producers. We take their picture and get excited to meet them, but we don’t treat people of color in cafes with even remotely the same degree of respect or consider that they’re a worthy candidate. It’s proximity to white culture and compartmentalization that exalts a person of color in one environment and disrespects them in another—that’s white supremacy, and it’s a foundation of how we do business in this industry.

Phyllis Johnson:

Do you know a coffee professional with lots of friends from Africa, but they can’t name a single African American friend?

Liz S. Dean:

I manage multiple cafe locations as the Director of Retail for Irving Farm, and when I look at customer complaints, the complaints I get the most are against my staff of color and my staff who are gender non-conforming. They can’t place them; ‘They aren’t smiling enough.’ It’s so unsettling to me and it’s something I think we need to talk about more—but I’m at a loss sometimes for how to talk about it, other than to tell my staff that I’m there for them and support them and they won’t get fired for not smiling enough. Compare that to in all the years I’ve been staffing for Irving Farm, I think I’ve received just one complaint about a cis male white staff member.

Tymika Lawrence:

I will never forget, I was in a meeting where a vendor was sending us the wrong information, and costing us money, and I was told—’Don’t get emotional.’ Or another time I was asked, ‘Are you angry?’

White men sit in a meeting and raise their voice, but if I raise my voice, who do you think they remember? People have unrealistic expectations of people of color and how they should manage their humanity. We’re talking about centuries of a legacy where people of color are expected to be subservient. And that’s part of the wider history of colonialization—how coffee got around the world in the first place, and how it’s harvested.

If you have a staff member that’s a person of color and you’re not thinking actively about how to support them and respect them, you are doing them a disservice, because those biases exist unless you are actively unlearning them. If you don’t respect them, do you think they’ll stay? That’s why coffee looks the way it does—it has to be your burning passion to ignore all that stuff and continue to push forward anyway.

Jenn Chen:

This is my third year of Expo in a booth. One of my clients is Acaia, the scale company—I handle all of their social media, writing, photography, and product launches. Two years ago we launched the Lunar Scale, and when it launched we had a huge rush to the booth and it sold out in 30 minutes—it was a crowded booth during the entire weekend. And yet I get people ignoring me when I’m in the booth. I’m totally capable of explaining all the technicalities and scale research and the manual and dissecting it down for consumers to understand—this is my job—but if you don’t want to hear it from me I can’t do anything for you. There would be groups of men that wanted to learn about the Lunar, but they would wait around to talk to the men in the booth, instead of talking to me.

Michelle Johnson:

People react so strongly to being called out, but don’t take it personally when it’s not about you. Stop making it about you. Stop the defensiveness. Stop asking us to do emotional labor.

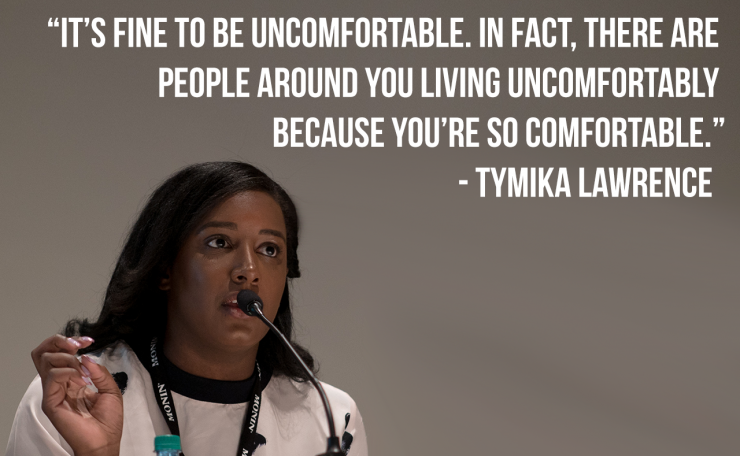

Tymika Lawrence:

The people we need to have these conversations with are not used to being criticized. People feel so comfortable giving me unasked-for critique—and no one should be impervious to critique, especially if someone is telling you the way you’re living your life is making it harder to live theirs—but I have no space for anyone’s defensiveness. People aren’t used to being critiqued and feeling uncomfortable, and when the shoe is on the other foot the instant reaction is defensiveness.

It’s fine to be uncomfortable. In fact, there are people around you living uncomfortably because you’re so comfortable.

Meister:

‘You get more flies with honey’—we hear that all the time. ‘If you didn’t act so mad about it’…well, why are we all so afraid of being uncomfortable with each other? What’s the worst thing that could happen? If you’re the kind of person who wants to grow and wants to have engagement, talk to the person about why you’re uncomfortable. Why is it so hard to apologize? Why don’t we just acknowledge that it’s really hard? I think women and people of color acknowledge that all the time.

Liz S. Dean:

Stop asking us to hand out gold stars for people being bare minimum human beings. I feel like when I engage with someone I have to spend the first portion of the conversation patting them on the back. I’m tired of it.

Tymika Lawrence:

This is not about you. It’s not about anyone’s feelings. It’s actually about the fact that these are structural inequalities when you’re trying to be a good white person or a good man—it’s not about you. It’s about world history. Remove yourself from the examination, except for when you’re looking at how you benefit from it. We live in a patriarchal society, and so if you’re a man, and you’re breathing, you benefit. It’s not about a choice—it’s about structural inequality.

If you take issue with my tone, and not inequality issues I’ve encountered thousands of times, you are a privileged person. If it’s more important to you that I’m kind, well, I have to tell you—you might not like what I said, but we live in a white supremacist patriarchal society, and I don’t like that.

Tracy Ging:

“If you’re white, notice how much space you take up. Notice how much room you yield. If you’re white, sit behind the podium instead of center stage. It does not hurt you or your career or your goals to sit down and shut up every now and then, and yield the space. Just be aware: you can do all the things you want to do without taking up all the space all the time.”

Phyllis Johnson:

Ask questions. And if you’re afraid of asking questions and having open discussions, go home and ask yourselves questions in the mirror. Don’t be afraid to learn someone else’s history. The pie gets bigger when you embrace diversity and inclusion, and you won’t suffer a loss. Your life will be empowered.

Get yourself and get your people. Research! There’s so much information out there. But I can’t give you historical facts on who I am. No one at this table can do that. It’s incredibly taxing, more taxing than I can tell you—and I know you worked hard, and your dad worked hard, but hard work has not been the same reward for everyone.

Understand that and educate yourself. We can’t educate you; your ignorance is taxing. We need you to fully engage—to stand flat footed and ready to learn and grow and feel uncomfortable. That’s the only way we’re all going to get through this.

Liz S. Dean:

You can’t only care about racism because your friend is black. You can’t only care about transgender issues because your brother is trans. Intersectionality is the whole package—it’s everything.

Tymika Lawrence:

What’s important for me is that everyone examines the way they oppress other people. Because that’s work—it sounds lovey-dovey, to say you need to love and value everyone the same, but that’s the truth. And as long as there are hierarchical worths in society that say, ‘you’re worth this if you look this way’ or ‘if you’re beautiful you’re worth this’, we will never be able to be an equal society.

It’s about work on the individual level to combat anti-womanness, anti-blackness. Everyone has work to do; the difference is the amount. And for white men, the work you have to do is more important. You exert more power, and you have more work to do. It’s important, and you need to do that work faster.

Phyllis Johnson:

I’m glad we can have these conversations now, and you won’t walk out of the room. I’m glad that we’re in an industry having this conversation.

Michelle Johnson:

Don’t get comfortable with progress. We have a long way to go, but it starts here, in this room. If you have that privilege, use it for good. We’re tired—we’re so tired —but it’s so necessary. I just can’t imagine how much further the industry could go, how much innovation could be happening, if the people like us didn’t have to spend so much time justifying our humanity and resume. We could be much further along, and together we can get there.

Photos by Lanny Huang for Sprudge Media Network.