Named after the folksy classic guitarist and composer from Paraguay, Agustin Barrios, this cafe within a store in the Philippine capital of Manila marches to its own drum. Cafe Barrios is uninterested in the “scene” of specialty coffee service, and rejects the label “Third Wave coffee.” So why feature them on a site like Sprudge? Because third wave or not, Barrios have created something altogether excellent, with an accent on serving Philippine-grown coffee beans that cater to a local palate and sensibility.

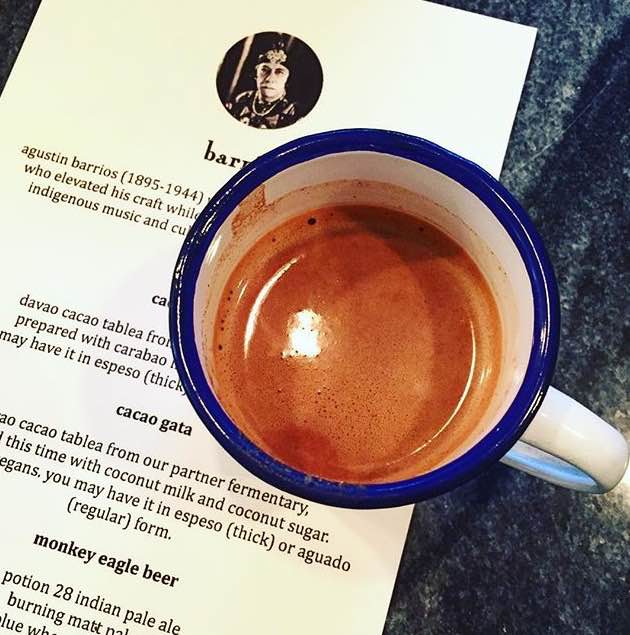

Outside in the noise and dirt, a sign reads “Languages Internationale”— spelled with an ironically superfluous letter at the end. Meanwhile, hidden up some wide cement stairs in what seems to be just a commercial building with little aesthetic appeal—call it old and kitschy if you will—is where Café Barrios opened inside the sustainable general store Ritual. Here they are serving mainly Nel Drip coffee, using both Arabica and Robusta coffee beans, plus hot cacao in tableau form, which they source themselves from the more rural provinces of the Philippines.

What started as a labor of love after the owners, Bea Misa Crisostomo and Rob Crisostomo, traveled extensively and worked in non-profit agriculture, has now become a new consciousness in retail. Ritual uses no plastic bags or bottles in their retail shop; you can think of them as a kind of nurturer to Café Barrios, supporting the cafe with organic food, green cleaning, and interesting tools for living. “We like to carry products from all over the Philippines and are super involved in the supplier process—from sourcing to processing to even heavier farm investment,” says Bea Crisostomo.

“Post-harvest in the Philippines is so deplorable,” says Bea Crisostomo. For Ritual, and therefore Café Barrios, the work is to get unique, market-ready products to their local clientele, and of course, for visitors popping in on the hunt for a great cup.

The neighborhood itself, somewhat newly dubbed “Outer Legazpi,” is central to the enormously sprawling Manila. A whirl of hamlets now connected by highways, byways, and a series of unidentifiable paths littered with decked-out “Jeepneys” (an altered Jeep that now resembles a rickshaw—just much louder) forms the greater metropolis of Manila. Café Barrios sits somehow in the eye of the storm: surrounded by Little Tokyo, Makati Cinema, the frequented shopping malls, and giant transit hubs.

Although coffee in the Philippines is dictated mostly by tiny sachets of Nescafé (just add scalding water and six spoons of sugar) in a few regions of the Philippines, a vibrant hot cacao and coffee culture exists. Bea Crisostomo calls these “totally democratic spaces” where early morning hot drinks are served with rice cakes. But the duo’s goal isn’t to force people to drink coffee in ways they might not prefer it—rather to get people to drink coffee from the Philippines. “For Ritual and Café Barrios, our goal is a better quality life for our producers and our consumers, that’s all,” says Bea Crisostomo.

“In the Philippines, most coffee work on the ground is done by women,” says Bea Crisostomo. She processes three species of coffee beans from the island of Negros—Arabica, Liberica, and forest-grown Robusta. Roasting is done with a copper roaster as well as a Gene Cafe sample roaster—giving Bea Crisostomo the caramelization that she wants.

“We honey process our Robusta and serve it as ‘kape gatas’,” says Bea Crisostomo, describing a local coffee drink that’s basically just coffee with milk. Here, it’s served with water buffalo milk. “We call it an upgraded ‘kapihan’ (a coffeehouse) staple,” says Bea Crisostomo. The grand tradition of coffee in this country came with Spanish colonization centuries ago—the Crisostomos are now trying to reinstate just that complete with a new standard of production, growing, and of course, roasting.

But in the Philippines, getting quality beans to market is a tightrope walk. In the forest on the Visaya Islands, where Rob and Bea Crisostomo work, the drying conditions are not optimal and the weather is at best unpredictable. But their hands-on approach (including working with their partner fermentary in Mindanao) means that standards can only improve. Perhaps the city, and even the country, is ready for a new wave of coffee sooner than expected.

Daniel Scheffler is an international freelance journalist whose work has appeared in T Magazine, Travel And Leisure, Monocle, Playboy, New York Magazine, The New York Times, and Butt. Read more Daniel Scheffler on Sprudge.

Top and final photo courtesy of Fruhlein Econar.