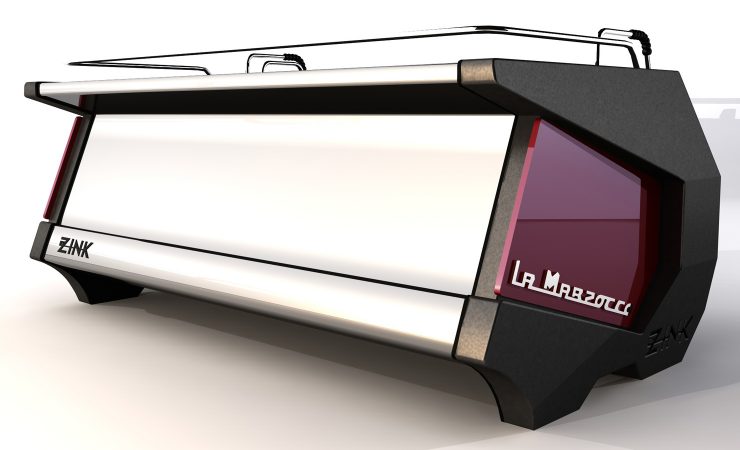

La Marzocco has described its ubiquitous Linea Classic as “a tried and true machine” that is “carefully designed to blend into any setting.” Sometimes that kind of staid stainless steel finish is what a busy coffee shop calls for. But in the same way that a cashmere crewneck sweater does not do it for everyone, a classic-style machine does not befit all bars, or at least not forever. Customization is all the rage these days, and here in the Netherlands some compelling work is being done by a brand called Zink.

Since early 2014, the Dutch design company has been elevating the unequivocally unlowly La Marzocco into something even more exclusive. Their current focus is on the looks of the Linea Classic, in its two-, three-, and four-group versions, though Zink has a long list of customization ideas for both inside and outside the machine, as well as for other models.

The two-man startup is powered by Tijs Wilbrink and Paul Schilperoord. The friends first met as undergrads in mechanical engineering and have, in the 20 years since, enjoyed comparing notes on “espresso design and culture.” Wilbrink, a business development specialist with past job experience at big-league corporations, such as IBM and ABN AMRO, oversees Zink’s marketing. Schilperoord is the creative director who—talk about opportunities for cross-fertilization—also works as a freelance designer for La Marzocco. If his name sounds familiar it may be because Schilperoord is credited for designing La Curva, the prototype lever espresso machine revealed at Out of the Box 2015.

With four series presently on the market and costs not too steep—prices range from 1,500 to 3,500 euros—Zink customizations have begun appearing around the world.

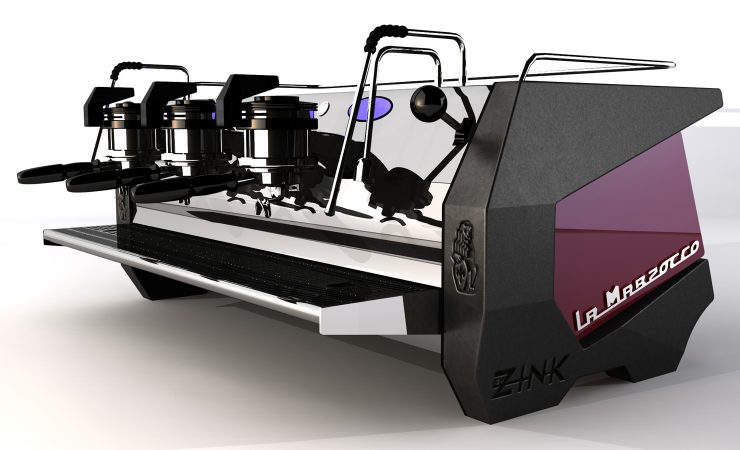

Most dramatic is the X1 series. To convert the Linea’s silhouette from upright parallelogram to sloping low-rider, Zink chops away parts of the original frame, most noticeably the upper back panel and cup tray. A rectangular window reveals a color powder-coated steam boiler. For the first two X1s ever made, red was applied, not only matching the La Marzocco logo that is steel-cut and fixed to the facade, but emulating the peekaboo engine of the Ferrari F430 that was Schilperoord’s inspiration for the design.

The first X1 debuted at a Mahlkönig booth during the 2015 Internorga trade show in Hamburg, Germany. The second, meanwhile, is seeing lots of action in the busy Dutch train station of Utrecht Centraal at ’t Koffiehuis en Bar. Its proprietors, HMS Host, have ordered a purple variation for their coffee bar at Café Chocolat in Lounge 1 of Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport.

Not ready to subject your Classic to metal grinders? Or, perhaps your aesthetic is less aerodynamically inclined? There are other—reversible—options.

Zink calls its three Z series “retrofit kits.” These don’t require a relinquishing of the machine because all the customized bodywork is shipped in a single box for self-assembly with the aid of basic tools.

“It’s not very complicated,” Schilperoord assures. “It’s basically loosening screws.”

The Z1 wraps two rows of colored steel around the rear and side panels, with pieces of honeycomb grille inlaid between. That kit has reportedly already found its way far from Zink’s workshop in The Hague, to clients in Seattle, Malaysia, and Australia—but there’s one in Amsterdam, too.

Essentially providing a customized façade, the Z2 replaces the machine’s original shell with colored panels and an upper glass pane bearing La Marzocco’s heraldic lion, plus space for a personalized logo. By spring 2016, the Z2 should be available via La Marzocco’s online store.

For a steampunkier look, there is the Z3. Its three glass panels expose all the mechanism’s inner workings, and neo-Victorian fantasies can be enhanced by sending Zink the original stainless steel boiler for a color powder-coating. Want an in-person Z3 experience par excellence? When next in Utrecht (after admiring the X1 at the rail station), go ogle the canary-yellow boiler and matching steel panel at the branch of The Village that recently opened in a former prison.

Though still just in their 3D rendering stage, customization designs are underway for La Marzocco’s GS3 and Strada as well.

“What I am interested in [is] going back to the 1950s espresso machine with these wild curves and exotic shapes,” says Schilperoord, discussing a computerized depiction of the Strada customization, tentatively named the Z4. “I do like the fact that there’s more body or volume to the machine, because some of the machines from the ’60s on, they’re really straight; also, the sides are really straight. So here, I’m trying to put more shape into the sides, so these sides are a bit bigger actually, and they angle up and they angle downwards.”

An appreciation for expressive vintage design may not be so unusual for a mechanical engineer who went on to get a Master’s degree at the Florence Design Academy and cherishes childhood memories of his father’s classic lever La Pavoni. The fact that Schilperoord is a Dutchman who moonlights with La Marzocco and is now building a Dutch business on customizing their equipment is, however, highly coincidental with the historical circumstances of a major industry player. That would be an individual whose high-end espresso machines, handcrafted in the Netherlands for decades, are synonymous with speed and style: Kees van der Westen, recently profiled elsewhere in these pages. If Zink persists, Schilperoord and Wilbrink may soon be keeping their compatriot in stylish company.

Karina Hof is a Sprudge staff writer based in Amsterdam. Read more Karina Hof on Sprudge.