The University of California, Davis, was host to specialty coffee’s first-ever Sensory Summit, a Roasters Guild of America event this past weekend. The university has become a taste-driven center of serious food and beverage studies that includes a honeybee research institute, a department of viticulture, and an olive center just to name of few. Members of the Roasters Guild, senior Specialty Coffee Association of America staff, enthusiastic QC managers from food companies nationwide, and coffee producers from El Salvador, Brazil, and Guatemala together spent two-and-a-half days frantically taking notes, brewing coffee, and tasting mysterious items in clear containers with three-digit codes, under the encouraging eyes of flavor industry professionals.

Nine sessions were interspersed with presentations from Davis professors in his or her field of food/beverage expertise, along with two SCAA courses where one could receive an SCAA Educational Pathways certificate.

The first session included a beginner’s booze tasting with four wines and a blindfold. With impaired vision, the audience was asked to smell isolated aromas before tasting a wine that complimented the scent. Leading the tasting with yogi-like grace was Henry “Hoby” Wedler, a Chemistry PhD student guiding coffee drinkers to focus their remaining senses in a different manner. Wedler serenaded the crowd through wine after wine, occasionally dropping flavor notes set to push the group’s indulgence—hazelnut in the pinot noir, green pepper in the chardonnay. This session was an appropriately passionate kickoff.

But on to the big stuff. A major takeaway from the weekend came from SCAA Science Director Emma Sage, alongside Molly Spencer, a Sensory Science graduate student, who presented on the new SCAA Flavor Wheel currently making waves across the coffee world’s collective Facebook page. The wheel and its accompanying lexicon, to be published by World Coffee Research, is a major update to the SCAA’s original flavor wheel, released twenty-one years ago. Presenting via Power Point, Sage and Spencer covered the reasoning and tools used to develop for this new wheel, with changes being made with the intent of improving communication and clarity. Sage asked, “If you have two coffees with the same score, how do you know that it’s different?”

There’s a need for definitions along with vocabulary, Sage went on. The lexicon and wheel were born from the data of a thorough process, which was comprised of a trained tasting panel (coined as “robot tasters”), a tasting panel of industry expert cuppers (which included Peter Giuliano of SCAA and Trish Rothgeb of the Coffee Quality Institute), as well as statistical analysis, which included results from a survey sent to SCAA members. This new wheel, Sage told the crowd, was built to be more intuitive to the cupper.

The lexicon provides a list of words with definitions, in addition to a 15-point intensity scale. These 99 words are placed on the wheel into nine major clusters, one of which is titled “Other”. Colors and cluster names were intentional and were born out of dendrographic hierarchical clustering. The new wheel controversially does not include defects, and many in the group found it lacking culturally appropriate descriptors to producers in the tropics, which stirred some debate during the session. Overall, the utility of the wheel—as a living communication tool for use in relating coffee character—was well-received by those in attendance, though its real utility test begins now, as it begins life out in the world in the hands of coffee professionals.

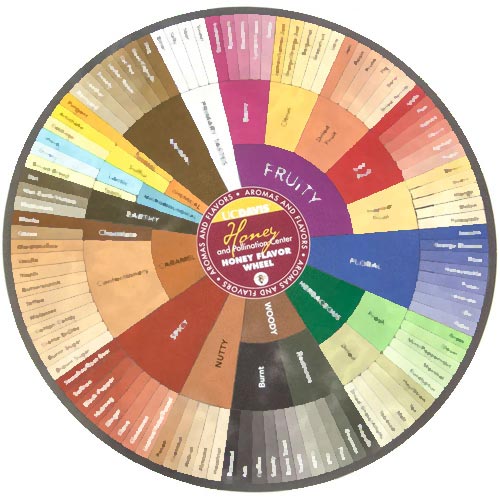

Few flavor wheels in food impress as much as coffee’s, but there was one sensory presentation during the summit that seemed to reflect issues in the sourcing process of coffee in an unexpectedly humanizing way. Amina Harris, Director of the Honey and Pollination Center at the Mondavi Institute (and recent publisher of honey’s first flavor wheel) gave a warm and impassioned 90 minutes on honey, from pollination’s role in the preservation of ecosystems, to the staggering genetically programed work ethic of bees, with a thorough sensory exploration of honeys ranging from horsey and medicinal aromas, to tropical, to cinnamon buns.

Refusing to accept “sweet” as a descriptor and to the obvious delight of coffee tasters, she talked the group through six honeys from distinct “forage” areas in California, Florida, Hawaii, Italy, and Canada, with a range of character to rival the variety of any natural food. The politics and improbabilities of forcing certifications on honey—a truly wild product—were made apparent, as well as efforts to, in her own words, “elevate the perceived value of varietal honey in commerce through education.” Not too distant-sounding a proposition for a coffee audience.

Dr. Harris’ session was the one that touched a motivational nerve for these writers. Sensory science begins with a specific fascination, one born from the discrepancy between how complex the workings of the natural world can seem by our limits of perception, and yet how passively and flawlessly they’re performed by nature. Dr. Harris exudes this original curiosity still, 30 years into her career, with such respect and advocacy for the process, the product, and the producers thereof.

Though reactions to the Sensory Summit may vary depending on one’s experience and career path, one fact was very apparent—public scientific resources relevant to the specialty coffee industry are limited. This event marked the beginning, a taste of coffee in academia; if UC Davis sets the example for sensory professionalism and coffee takes its cue, then dedication from and funding for those who want to pursue academia is a must. For the next Summit, let there be more research presentations, more QC strategy from food industry leaders, and less survey-level material. This must be the beginning.

Juliet Han is an American coffee professional based in Oakland, California. Read more Juliet Han on Sprudge.

Charlie Habegger contributed to this reporting.