It’s a chilly autumn night in the Loir-et-Cher and Noëlla Morantin is pouring glasses of Tango Atlantico, her new Côt and Cabernet Franc blend. The wine, rich and structured, marries jammy Cabernet fruit with characteristic Côt tannins. Morantin is sharing her wine, but she’s also sharing advice with Lisanne Van Son, a young sommelier who has moved to the region to work with Lise and Bertrand Jousset and to make her own wine as well. Tomorrow she will bottle her first cuvée of pétillant natural and she’s nervous about doing it on her own.

“Everyone will have advice for you, but you have to make decisions for yourself,” Morantin tells her. “That’s how I’ve learned everything…that’s what makes us better winemakers.” The advice seems to be exactly what Van Son needed to hear—encouragement from an experienced winemaker validating her ability to make her own decisions and her own wine.

These are the kinds of moments that make me grateful to live in French wine country, to get a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the real work of winemaking—accumulating and sharing experiences, errors, convictions, and confidence. The advice feels sacred, an established winemaker passing on hard-earned knowledge to the next generation.

Morantin has earned the right to advise after 15 years of making wine. This year marks the 10th year that she has been working under her own name, and it’s clear that the anniversary has special meaning to her. It’s a milestone she references frequently in conversation, a badge she wears proudly.

“I’ve had the same idea since I started making wine and I’ve always followed it: I want to make wine I enjoy drinking,” Morantin told me when I visited her newly constructed wine cellar minutes from the winding Cher river. This objective may seem obvious, but in the world of natural wine—where definitions of drinkability are as varied and unique as winemakers themselves—the term is open to interpretation. Natural wines can range from wild and without sulphur—recognizable for their barnyard smells and reduction—to controlled cuvées that refuse to deviate from a predetermined path. Morantin’s wines have carved out a niche in between the two—resulting in elegant natural wines that please drinkers of all persuasions.

The influence of her early mentors, Marc Pesnot of Muscadet and René and Agnès Mosse of Anjou. After learning from these Loire region role models, Morantin began making wine on her own for Japanese wine importer Junko Arai, who managed the domaine Les Bois Lucas in Pouillé. “I loved the wines I made for Junko,” Morantin told me, explaining that this period is when she began making wines, and decisions, for herself. Morantin would then go on to buy and rent (from the neighboring Clos Roche Blanche) wines in the village and in 2007 began to vinify under her own name.

Making wine is a series of decisions. To discover a wine is to discover a person and a place, but also a protocol. In her early years of winemaking Morantin developed convictions that led to the decisions that make her wine entirely her own. The choice to add a minimal homeopathic dose of sulphur at bottling, for example, was one she didn’t hesitate to make. “I know very few people who can make excellent wines without sulphur,” Morantin told me, citing Pierre Overnoy and Michel Gramenon as examples. “I’m not saying ‘long live sulphur,’ but for me, what works best in my wines and the wines I like to drink, is one gram of sulphur [per hectoliter], I think the wine needs it.”

Morantin also made an early decision to sell her wines on a first come, first serve basis. Despite seeing the enormous success of natural wines abroad, Morantin has always sold wines to whoever wanted them, allowing markets and interest to develop naturally. This year, her sales have been half to the international market and half sold domestically within France, a happy coincidence for Morantin. “I think it’s important to have my wine sold in France, I could sell everything to the United States or Japan, but why? I decided to make wine in France and I’m French, so for me it’s important to sell my wine in France.”

As the threat of frost has increased in the region, Morantin has been forced to make new decisions. Last year, her vineyard lost 90% of its grapes during the frosts and it became immediately clear that she would have to buy grapes if she wanted to make wine this year. “My first criteria was to find organic grapes,” Morantin said, “I’d rather go far away to get organic grapes than to buy in the region but non-organic.” But the possibility of making wine with grapes from another region didn’t appeal to her, “I didn’t want to say, ‘Hey I’ll make Carignan this year,’ because I have no mastery of that grape. It would be strange to make wines with grapes I don’t know.”

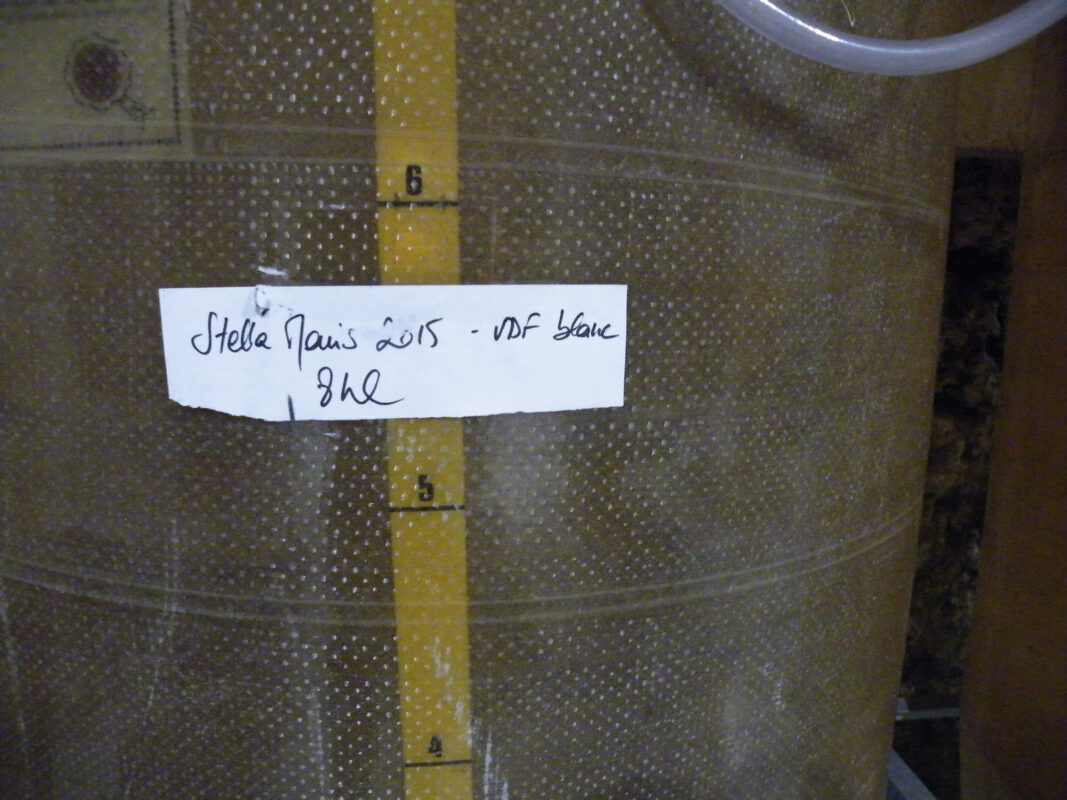

Fortunately, a local winemaker had organic Sauvignon, Gamay, and Côt for Morantin and as the juices ferment in the cellar after the 2017 harvest, it is clear that Morantin truly knows these grapes. In the coming months, Morantin will guide the wine until it becomes the well-loved vintages including Chez Charles, Côt à Côt, Mon Cher, and the newcomer, Tango Atlantico. Morantin is also releasing a special vintage this year, Stella Maris, made from the 2015 harvest from her old Sauvignon vines (planted in 1943) and barrel-aged. The name is a reference to the motto of her fishing village hometown Pornic—Maris stella sit nobis propitia (May the starfish look favorably upon us). “I’ve always wanted to make a wine linked to my origins,” Morantin explained. It seems fitting that the wine will be released as Morantin celebrates her 10 years of winemaking on her own, serving as a reminder of the importance of remembering your origins and sticking to your convictions.