Many coffee companies—in particular certain very large, multi-national brands—are quick to champion their sustainability efforts through public, vocal, and expensive marketing campaigns. Most will contain boilerplate appeals to emotion, invoking names and images of producers said to be the benefactors of the brand’s initiatives. We’ve been critical of some of these efforts in the past. While any aid to struggling producers is great, it nonetheless needs to be viewed within the context of what the companies pay for their coffee when no one is looking; if they’re not paying a fair, sustainable price for the hundreds of millions of pounds of coffee they buy each year, throwing a highly-public few M’s at the problem is hardly the philanthropic endeavor it might seem at first glance.

And now a new report from the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment finds what some have suspected all along. In analyzing the buying practices of 10 large coffee companies, they found that “none can guarantee living income or living wages within their supply chains.”

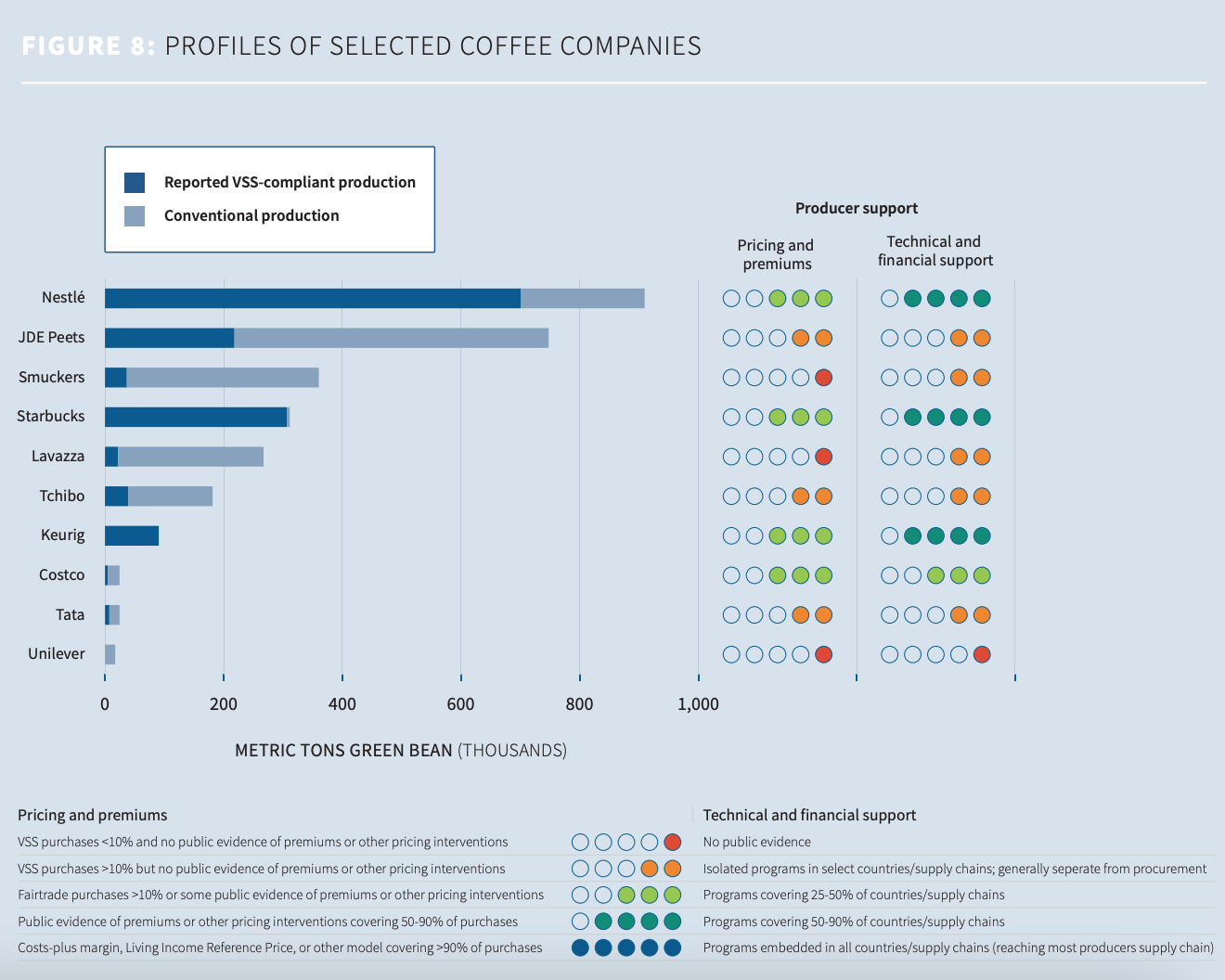

Released last week, Responsible Coffee Sourcing: Towards a Living Income for Producers looks at the coffee buying of global brands Nestle, JDE Peet, Smuckers, Starbucks, Lavazza, Tchibo, Keurig, Costco, Tata, and Unliver. In the 72-page report, each company’s practices are broken down and analyzed based on how they contribute to a farm worker’s living income—a “net income necessary to afford a decent standard of living in a specific place income,” including the ability to “afford a healthy diet, good quality housing, critical elements of health care, education, and transport, and that they can have a margin for savings and emergencies”— and living wage—the wage “received for a standard workweek by a worker in a particular place sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker”—as well as suggestions for each company to improve their practices.

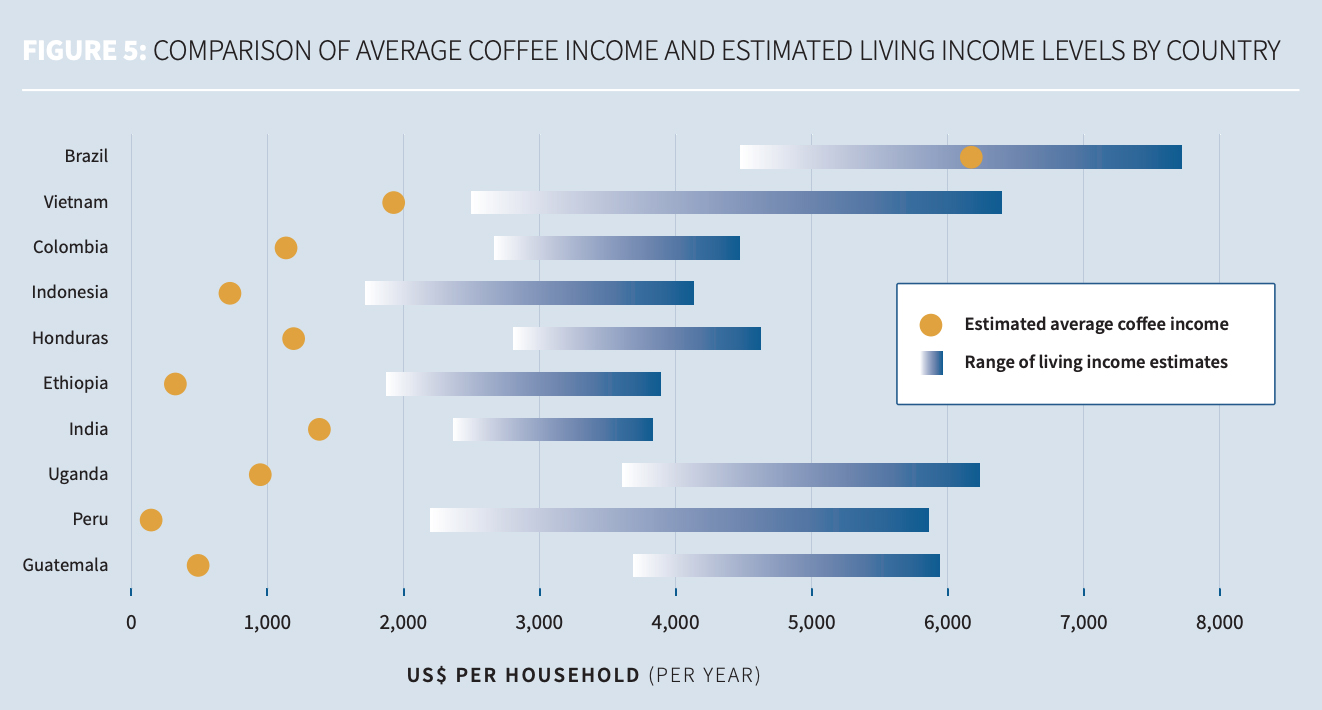

When looking at the 10 companies, the researchers found that, while nearly all brands had some level of sustainability initiatives—including paying a premium for coffee with a Voluntary Sustainability Standard (VSS) certification, like Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, etc, which the report notes that there is no evidence that “any VSS alone would enable most producers to achieve a living income”—not one was found to broadly pay a livable wage or income. In fact, when breaking down the average coffee income in the 10 largest producing country, the report found that eight of ten had averages at or below the poverty line; only Brazil had an estimated average income “above some living income estimates.” On the other end of the spectrum, Uganda “has the largest gap to living income, with an average coffee producer earning $88 per year from coffee, relative to living income reference values that range from over $2,000 to nearly $6,000.”

The report offers many broad suggestions for closing the living income gap for producers, including producer support, changing business practices, and the one we’ve been calling for all along: raising prices and premiums, which they call “ the living income lever that is most ignored by companies.” Unsurprisingly, in assessing each individual company’s areas of improvement, every one included a suggestion of disclosing some level of price paid for coffee; read: please release a transparency report, something we’ve been ardently suggesting for some time now.

In the end, the exhaustive and well-researched report by the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment finds that, contrary to the marketing campaigns, all of the world’s largest coffee companies still have a lot of work to do in order to provide their producer partners with a real, livable wage. The full report can be found here.

Zac Cadwalader is the managing editor at Sprudge Media Network and a staff writer based in Dallas. Read more Zac Cadwalader on Sprudge.