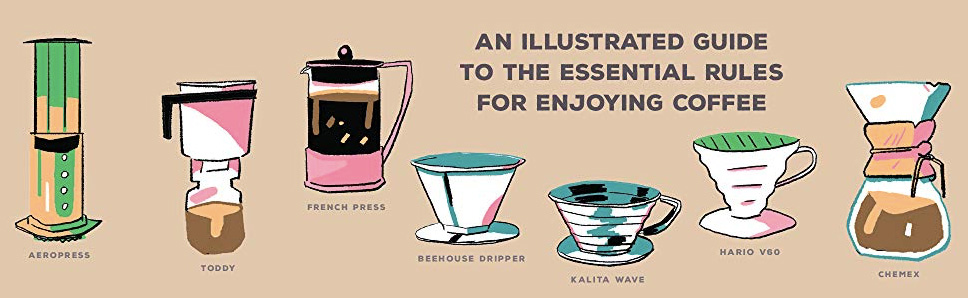

In coffee, true global icons run few and far between. Germany has Melitta Bentz and her conical ubiquity. Italy has the Bialetti—and just about everything else having to do with espresso. And in the United States, the sleepy domain of low-brow automatic drippers and diner brews, we’ve got one pinnacle of brewing and design with more than one mysterious lifetime behind it. From its birthplace in New York City to its present-day surroundings in an office park in Western Massachusetts—the USA? Why, we lay claim to the Chemex.

That laboratory-chic carafe that’s ruled kitchen counters (and museum shelves) since the 1940s goes beyond a mere coffeemaker with a story. It is, in fact, a coffeemaker with two stories: its formative years at the hands of would-be-mad-scientist and bon vivant Dr. Peter Schlumbohm, up to now, where a recalcitrant family of quiet custodians has seen the brewer into a new era of coffee in which it’s been heralded, even cult-ified, with little more marketing push in three decades than a box redesign. For years, I’ve wanted to know more, and for years, I tried to find out.

***

Chemex first launched in the 1940s, then made a resurgence in the coffee landscape in the late 2000s, when Third Wave and Third-Wave-ish companies embraced the brewer, perhaps most notably in a full-court-press from Intelligentsia to laud the device as a superior way to brew, and present, special coffees. “The honest truth is I love the coffee that comes out of it,” said Intelligentsia co-founder Doug Zell when asked what led him to shift the brewer to prominence in the company’s cafes. “It works well with our sweet, clean coffees and also think from a design standpoint it is simple and beautiful. At the time, I liked that it was different and not widely used.”

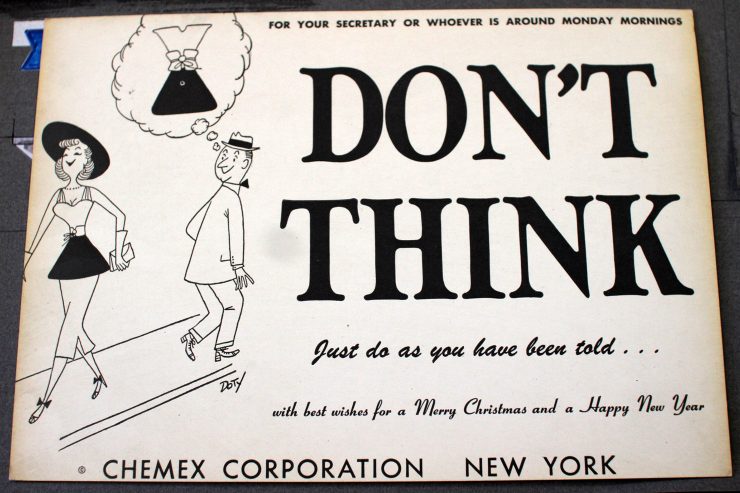

Yet despite the increased attention cast on Chemex, its current owners—a family of mother, daughter, and son in Massachusetts—maintained a reserved and spotlight-shunning public stance, almost the antithesis of Dr. Schlumbohm, who, the company’s records would indicate, spent most of his leisure time shipping out Chemex brewers to A-list celebrities of his day when not inventing new tools to chill cocktails. When I first met Adams Grassy, second-generation of this contemporary Chemex-owning family (his parents, Liz and Patrick, purchased it from the previous owners in the early 1980s), it was at a crowded and annoying party in Portland, Oregon, during the 2012 United States Barista Championship. “This is Adams Grassy from Chemex,” Intelligentsia’s Zell said to me in the crowded nightclub, and I was sure I’d heard him incorrectly. No one from the Chemex corporation had ever been spotted in the wild, had they? Much less around a cadre of reveling baristas who’d surely cover anyone from Chemex with geeky barista drool.

I got Grassy’s Chemex-themed Gmail address, and would spend the next three years persistently angling for an audience with the family and the factory. It seemed every time we’d finally agree upon a date for me to come up from New York, there would be a delay: a factory move coming up in a year, a postponed factory move, the floors weren’t done yet, a hurricane. By the time I boarded my train to snowy Massachusetts in late February, it seemed the company might still have time to back out.

***

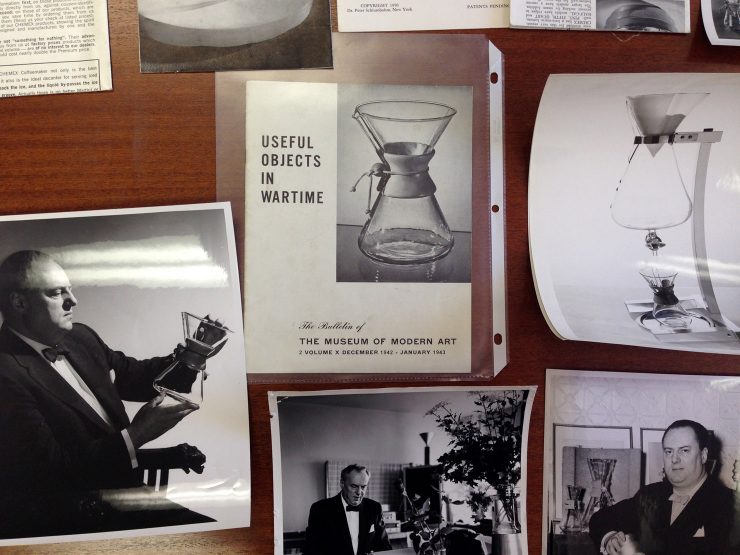

When you arrive at the Chemex factory the first thing you need to know is that it’s not exactly Willy Wonka-land. Glass is not blown here in magical rooms full of hot flowing liquid with elves sawing perfect wooden collars and pixies affixing them with perfect rawhide ties. The majority of Chemex’s components are brought in from faraway outside suppliers: glass formed in Croatia and Taiwan, wood from Malaysian rubber tree plants, and those racy leather ties from Rawlings, the baseball mitt manufacturer, down in Tennessee. What is manufactured at Chemex are coffee filters. Lots and lots of custom cut and folded bonded paper filters, round and square, natural and white are made here. Filters zoom off the assembly line next to stations for quality control of Chemex brewers themselves, assembly of leather ties and beads, packing, and shipping. The space itself is nondescript, but the quiet, would-be museum of Chemex that exists within the folders, binders, and picture frames preserved by the current owners reveals a crazy adventure through American inventing history. And, indeed, the facility itself—half-production-and-shipping and half-business-administration, mostly conducted from quiet desks—is a testament to the shifting, or rather shifted, state of American manufacturing.

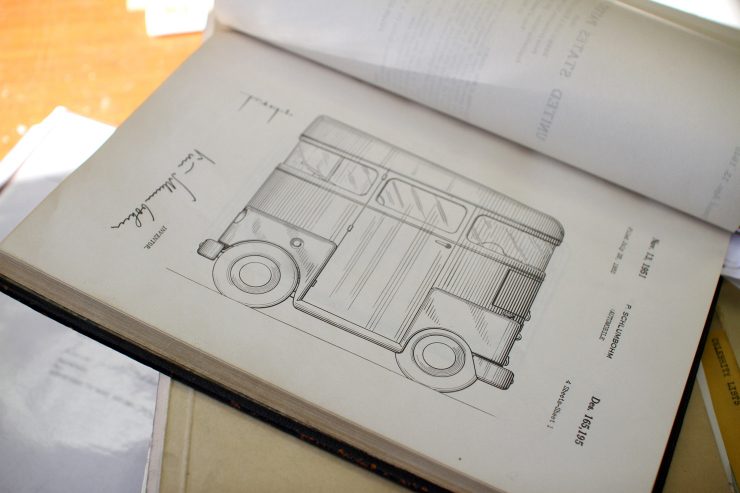

But let’s not jump ahead too much. In fact, let’s go back to 1896, when Peter Schlumbohm was born in Kiel, Germany. Though he eschewed a spot in his family’s chemical business, he left home to study Chemistry anyway (and Gestalt psychology!), eventually landing in New York City in the fast throes of the invention and patent game. Though obsessed with refrigeration and chilling, it was the invention of the Chemex coffeemaker, based on a patent Schlumbohm secured in 1939, that set sail his legacy on wings made of oddly-folded coffee filters.

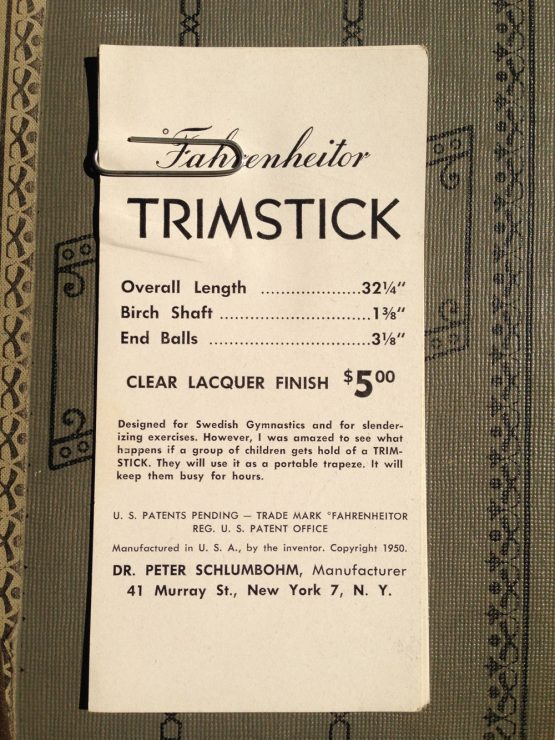

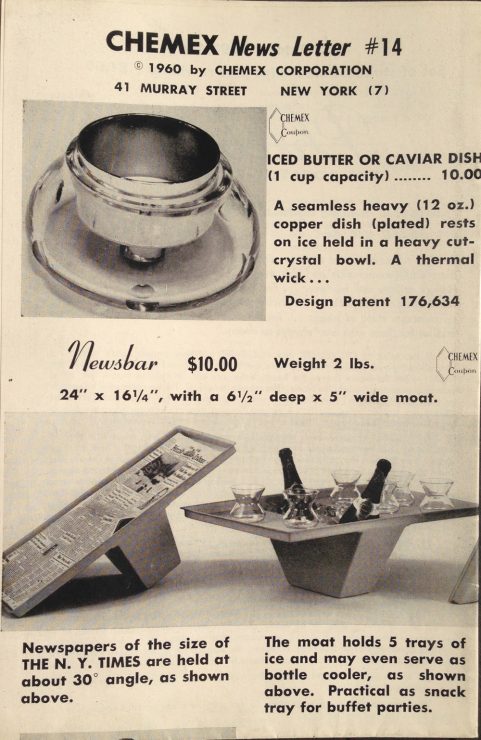

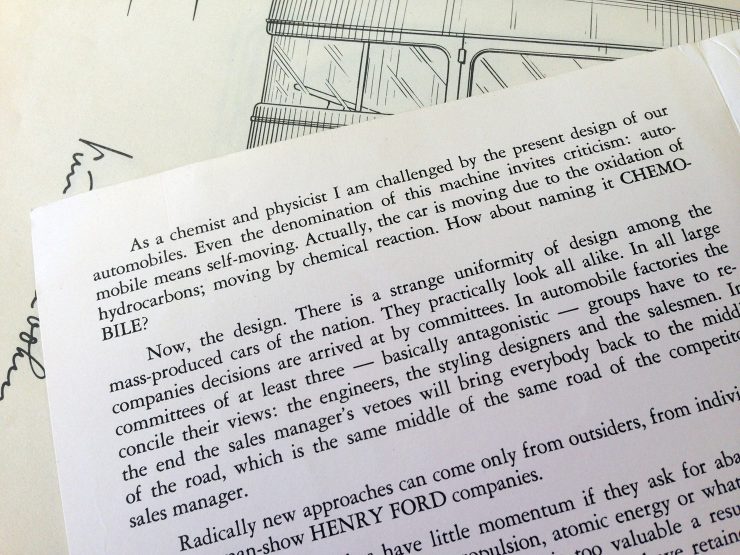

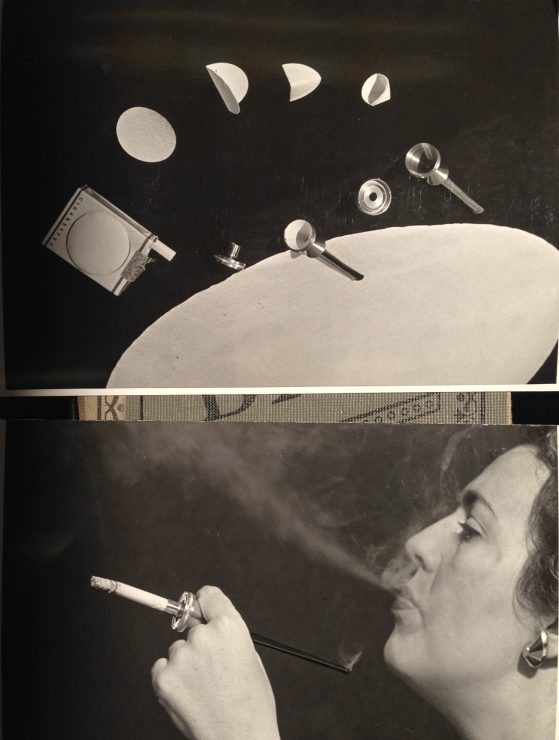

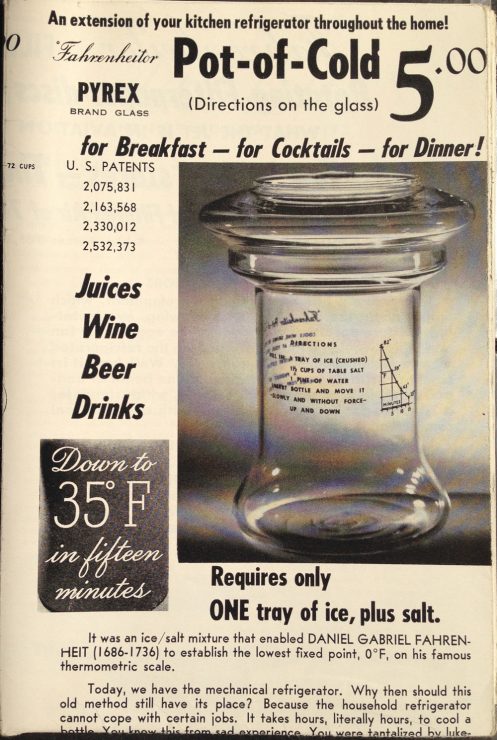

The wheels of Schlumbohm’s mind seemed to perpetually be turning with life- (and lifestyle-) improving inventions often focused around central themes. The Chemex coffeemaker itself inspired many of them: air-circulating fans that incorporated the Chemex filter. Cigarette holders with a miniature Chemex shape, and, yes, miniature Chemex-filter filters. And myriad other accessories to finer living: A thermal-wicking-cooled caviar dish. A mushroom tray. The Fahrenheitor cocktail freezer. The Newsbar, a drink-chilling bed-tray with a moat for keeping your Champagne on ice that later flips up 45 degrees to hold the New York Times at an ideal reading angle. The Teamex. The Pot of Cold. Juice glasses, hi-ball glasses, cocktail glasses, beer glasses, a “Jet cooler”, Tubascope sun spectacles, and also, a car.

A car? Yeah, there’s a car, too, named a “Chemobile”—because, as Schlumbohm pointed out, so-called “automobiles” move because of chemical reactions, not on their own.

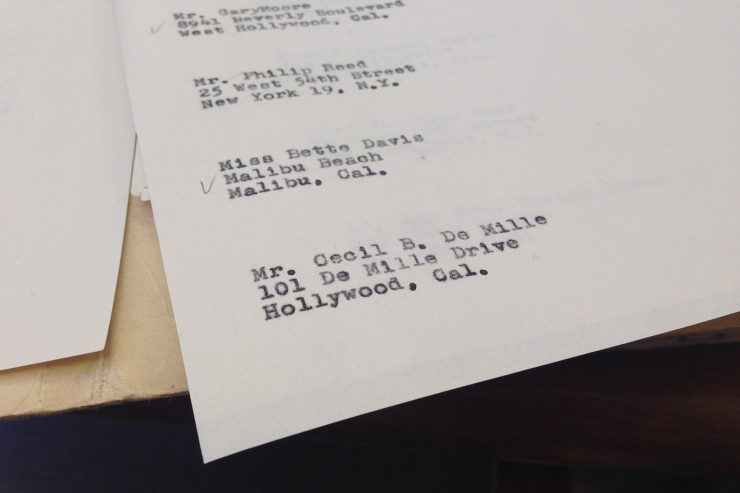

Schlumbohm’s magical universe extended well beyond the drafting table and all the way up to high society. With every invention made, a copy was sent to the Museum of Modern Art for its consideration. Personal appeals for endorsement of the Chemex were made to all the A-list celebrities of Schlumbohm’s day—Burt Lancaster, Lucille Ball, Cecil B. DeMille, and Catherine [sic] Hepburn are but the tip of his mailing list’s iceberg. From the nightlife to the customized Cadillac with gold-plated Chemex hood ornament, it would seem Schlumbohm’s love of high society equalled his love of high design.

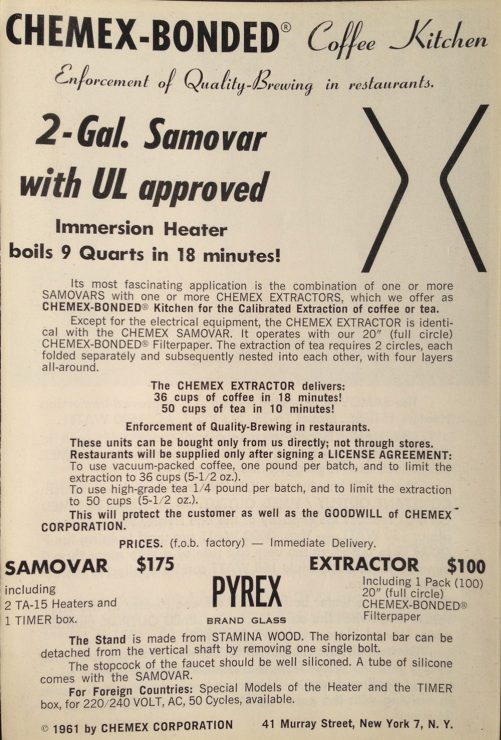

But was he crazy? At least not completely. Print materials for the Chemex Extractor, a 36-cup brewer which mounts a large Chemex “Samovar” on a stand with dispensing spigot, detail precise standards which specifically address the concerns of quality restaurant coffee preparation that continue today. Under the heading “Enforcement of Quality Brewing in Restaurants,” Chemex restricted use of the Extractor to only establishments which had signed a license agreement. Only one operator was permitted to brew and serve from the coffeemaker, and only to Chemex’s brewing parameters: coarse grind vacuum-packed coffee, 1 pound per batch, to yield 36 5 1/2-ounce cups in 18 minutes. While these are unlikely to be the specifications we’d select today, the company’s strict stance on variable control—in the world of 1950s restaurant coffee!—is admirable if not amazing.

***

When Schlumbohm passed away in 1962, he left the Chemex business not to an heir, but rather, to a favorite female assistant within the company. Less of a refrigeration and coffee-brewing enthusiast, apparently, than Schlumbohm, the new owner quickly sold the business to businesspeople in Pittsfield, Mass., near the Berkshires. This ’60s and ’70s era of Chemex saw an expanded move towards the housewares sector: blenders, food processors, and similar devices. After a time, Patrick and Liz Grassy—he, a former FBI agent and prosecutor, and she, a member of the fashion world, who’d both lived on the Upper East Side of New York City—heard from a relative that the Chemex folks were looking to sell. Already fans of the brewer and brand, the Grassys jumped at the chance, and moved out to Liz’s native Massachusetts to run the company. They were, as it happened, through with the FBI life and ready to settle somewhere more tranquil with their children anyway.

“Chemex is my earliest memory,” says Adams Grassy, who now runs the company with his mother and sister (Patrick passed away unexpectedly in 1998). “To me it was an extension of the family, this is part of the family, where my dad was all day. After school, that’s where I’d get dropped off. They bought the company and it was stationed in Pittsfield, and very quickly relocated it to an old paper factory in Housatonic. My father actually purchased an old mill, and moved Chemex into it, probably in 1983, right around there. I’d get dropped off after school and go into the office area or right down into the shop,” remembers Grassy. “There was a lady there named Kris who oversaw the glass assembly as well as the old automatic assembly. So I’d help her with brewers or putting very easy stuff like rubber stoppers into the automatics.”

Grassy’s parents wanted to move away from the different directions the company had started going in with blenders, and just concentrate on coffee-related products, says Grassy, and they did—alas, not to immediate success.

“Business through the ’80s and ’90s dipped significantly,” said Adams Grassy, “as a result of that, it didn’t make much sense to be in a large paper mill.” The company ended up relocating back to Pittsfield in the late ’90s, and remained there up until a recent move to Chicopee, Mass.—closer to Springfield—late last year. Sales picked up around 2005.

“Smaller roasters and coffee shops, out of the blue, would reach out to us and begin a dialogue,” said Grassy. And though, like Schlumbohm, Grassy had initially diverged from the family trade, he suddenly found himself back in the mix. Setting aside aspirations in parks and recreation, he accepted his mother’s invitation to join the newly bustling Chemex in 2010, along with his sister Liza. Business was good again, and more hands who cared about the company were needed on deck. The industrial park building the company now occupies in Chicopee today staffs about 25; this includes filter die-cutting and folding machine operators, the people tying those Rawlings ties into a perfect knot, and of course, the Grassys. “All of our machines have an operator for them, so everything is one way or another assembled by hand, we don’t have anything fully automated,” says Grassy.

In late 2014, though, the company that had shied away from electronics-driven products for decades revealed a new, yet old, invention. Since the Chemex folks are so terribly quiet, it’s no huge surprise that the announcement of the “Ottomatic” automatic Chemex brewer came as … a huge surprise. Ottomatic, conceived in partnership with Irish hot-water force Marco, was a years-long R&D journey conducted largely over Skype and international shipping. Most of the outside coffee world never saw it coming. For Adams Grassy, though, it was not only a necessary addition to the catalog (particularly while it’s still in vogue to shove a Chemex carafe under a Bonavita automatic brewer or incorporate it into your cafe’s Modbar setup), but a link to his family’s own past.

“When I joined the company full-time in 2011, that was one of the first things I thought of, because my earliest memories were of the automatic,” said Grassy. “We heard from existing customers and potential new customers that they’d be interested in it, and I wanted to attract new customers we were reluctant to use Chemex on a daily basis because of the manual steps that need to take place for that to happen.”

Ottomatic, which is slated to ship officially this spring, retails at $350—Chemex carafe included. It joins a new era of products that improve upon or pay tribute to the Chemex, though unlike the Able Brewing KONE filter and heat-saving lid, or Intelligentsia and Horween Leather’s custom collar, this is actually made by the Chemex corporation itself. For coffee drinkers, it’s a handsome (if high-priced) take on a favorite, and an easier way to brew daily in a beautiful classic.

And speaking of brewing daily, I just had one more thing, after all of Grassy’s storytelling, and the hours spent paging through Dr. Schlumbohm’s legacy, that I just had to know.

Does everyone who works at Chemex make Chemex coffee at home?

“I think everyone here has a lot of Chemexes,” said Adams Grassy. “We have some we just can’t send out because of a slight cosmetic flaw, so I think everyone here has a lot. I’d be surprised if any of our employees have less than three of them.”

Grassy continued: “We have used a Chemex for pretty much everything. I’ve used the Chemex camping, I’ve used it to put salt out on the sidewalk before. We’ve used it for parties to have alcohol-infused fruit in there.”

You know—I think Dr. Schlumbohm would have approved.

***

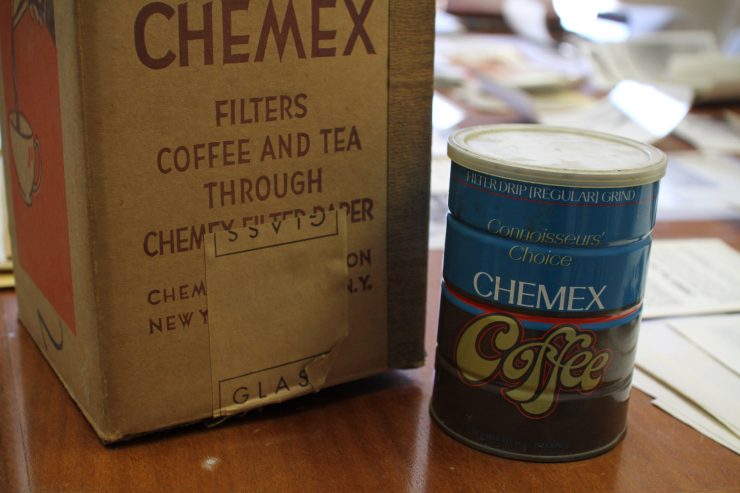

Scroll through to see some of the best ephemera from Dr. Schlumbohm’s era.

All photos by Liz Clayton.

Liz Clayton is the Associate Editor at Sprudge.com, and helms our NYC desk. Read more Liz Clayton on Sprudge.