While you can’t obtain a degree in coffee (yet), you can use it as a teaching tool for chemical engineering, plant science, and sociology. This interdisciplinary approach has been a decade in the making and is now cemented as an official building on the University of California, Davis campus.

The “Design of Coffee” course in the College of Engineering skyrocketed from a fledgling class of 18 students in 2013 to serving over 2000 students a year, making it one of the university’s most popular elective courses. This growth led to the creation of the UC Davis Coffee Center, which had its official ribbon-cutting ceremony in May. The Center is both a people and a place. “The point of the building is to serve as a nexus for all those different intellectual disciplines,” explains the Center’s co-director and professor of chemical engineering William Ristenpart.

I dropped by the Center for a tour and to speak with folks involved with the Center and how it came to be. Walking into the lobby, you’ll see a wall with a coffee tree and branches/leaves labeled with names. This may seem like a typical donor wall for many visitors, but for the Center, it’s a heartfelt thank you to the companies and individuals who invested in its potential. It’s 100% philanthropically funded—a rarity for university buildings and renovations—and this fact is evident throughout the building.

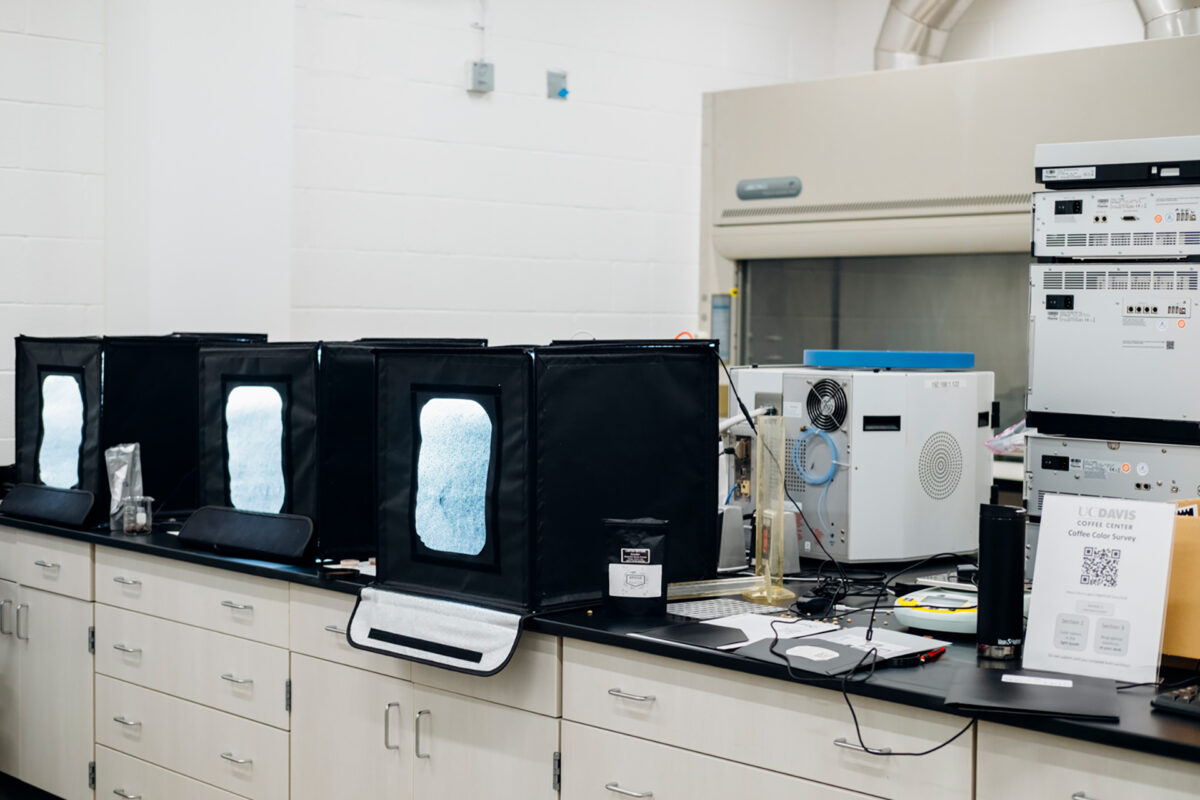

Inside, the rooms are connected by the Cropster Corridor, for how the software connects various points of the post-harvest coffee chain. Rooms are separated out for the Peet’s Coffee Pilot Roastery, La Marzocco Brewing and Espresso Laboratory, Nicaraguan Coffees Green Bean Storage Laboratory, Folgers Analytical Lab, Toddy Innovation Hub, and a sensory and cupping lab with individually named sensory booths.

The brewing and sensory labs connect via a shared blackout window. To easily carry out sensory work, one could brew in the lab and pass the sample over for sensory analysis without introducing bias. In the pilot roastery, roasters are set up for research studies and to production roast for bags sold in the bookstore. A wide assortment of coffee and food lab equipment serves as a base to guide future research studies.

I remember learning about the undergrad course conceived by chemical engineering professors Tonya Kuhl and Ristenpart. I had just moved to the Bay Area, and here was this nearby college offering a lab course that I would’ve loved in my own undergrad studies. It certainly would’ve made my chemistry classes more interesting.

If you work in coffee, you know how easily people will chime in about their love of it: people have opinions, rituals, and memories, all tied to this product. So when the course launched, the local news took notice. There was a news spot and articles, and the Specialty Coffee Association of America (now the Specialty Coffee Association) saw the hubbub and flew in to check it out.

According to Ristenpart, it became a moment of clarity where “it very quickly became very clear that the coffee industry badly needs more academic education and research.” UC Davis already had buildings and complexes for other beverages: a pilot winery, pilot brewery, vegetable processing facility, and food innovation lab, to name a few. But nothing for coffee. In fact, there wasn’t an academic center for coffee anywhere in the US. There were certainly pockets and labs that were exploring coffee, but they’re meticulously focused on one discipline, not across many.

The stars aligned, he recalls. Not only was (and is) coffee science research needed, but a building was vacated, and Peet’s Coffee reached out about making a philanthropic contribution. Peet’s founding gift catalyzed the Center’s start with a pilot roastery, and Ristenpart spent the next eight years raising funds. Instead of renovating it room by room, which would’ve incurred small fees that added up, they decided to do it all in one go. The real estate and building may have been donated by the university, but the insides were not suitable for any of the center’s needs. It was gutted; everything from mechanical to plumbing was replaced, and walls were moved. He says, “Now it’s a Center that’s very explicitly and consciously designed to facilitate coffee research.”

The construction project cost $6.2 million, of which $4.5 million has been raised. The rest is a construction loan that must be paid back—having this on the books means that fundraising can’t be focused on fellowships or direct student support yet. Ristenpart shares that he has more students interested in researching coffee than the monetary means to fund the studies.

The Center’s interiors are also being finished. On the day of my visit, a few dozen firefighters trooped through to familiarize themselves with the building. Furniture and other lab equipment need to be moved into some rooms. But even during the buildout in 2022, when everything had to be moved out to various labs on campus, research continued, and papers were published.

There’s been Toddy-supported research into cold brew, Probat-supported research in roasting, and collaborations with the Coffee Science Foundation (CSF) and SCA. “There’s not a lot of congressional or government support for coffee research. That means basically the coffee industry has to stand up to support it,” says Ristenpart. “We’ve been very fortunate that there are a lot of very forward-thinking companies who have supported coffee research.”

One of the Center’s turning points was the first full-time hire from the specialty coffee industry, Juliet Han. It was a three-year fellowship funded by Probat, and a signal to the industry that the Center was committed to working together. More equipment and monetary donations followed.

Chemist Sara Yeager completed her master’s thesis at the Center and spent a year afterward working on Toddy’s research and development team. The newness of the Center worked in her favor. She shares, “It was a really fostering environment where my ideas were heard and taken in stride, and my thesis was able to be my thesis rather than someone else’s pet project.” Unfortunately, COVID hit, and she had to scrap some of the planned work. Half of her thesis was done in the lab and the other half was virtual—a meta-analysis of chemical composition. For her lab research, she took regular samples during the cold brew process. On top of TDS measures and percent extractions, “those coffee samples were also used for mass spec analysis later on for the organic acid content, so that way we could tie physiochemical data to the sensory data that we were collecting,” she explains. Yeager’s researcher was part of a larger set of research on cold brew, underwritten by Toddy.

As a chemical engineering undergrad student, Reece Guyon was tasked with testing batch brewers for the SCA to determine if they passed the Certified Home Brewer Program. Lining up several brewers at a time, he would go through the checklist and provide feedback on the prototypes. Guyon was first drawn into the Center because there seemed to be so much untapped potential in research studies. With its establishment, he says, “I think it’ll help get students more involved—it’s got all the great gadgets and everything like that— people can think up new ideas on how to brew it, how to make it more sustainable.” Post-graduation, Guyon now works as an optical network engineer.

I don’t think anyone would disagree with the need for coffee science research. What gets ignored in the post-harvest studies, though, are practical applications in a retail or roasting environment. It’s one thing to know what factors are best for a fully extracted espresso, but it’s another to feasibly apply it in a fast-paced cafe environment.

“What is missing is the actual scientific backing to most of these claims,” says Laudia Anokye-Bempah, a graduate student pursuing her Ph.D in biological systems engineering, referring to her kinetics of coffee roasting study that explores “the effect of roast profiles on the dynamics of titratable acidity during coffee roasting.” Going deeper into the coffee industry has been eye-opening for her, especially after attending SCA Coffee Expo. “You get to see so many people from different aspects of the coffee chain, from buyers, importers and exporters, roasters, and we all come together and basically speak a common language. The connection and available opportunities in the industry have been mind-blowing for me.”

Roasters knew that “if you change the roast profile, you can make it taste more acidic, or you could make it taste more bitter,” but not the why, explains Tim Styczynski, the Center’s head roaster and owner of Marysville, CA-based roaster-retailer Bridge Coffee Company. Bridge Coffee also made a $50k gift to build the bridge connecting the arboretum and the Center. Styczynski is particularly excited about the Center’s potential. “I love that it starts with green coffee research, goes through roasting research, and it’s incorporating brewing research,” he says. “I’m super excited that it’s adding sensory science. So that whole aspect from sourcing to drinking coffee.”

Anokye-Bempah’s research also explores color and the creation of a universal color curve in roasting. It’s the difference between a one-dimensional Agtron score and a three-dimensional L*a*b* space that color scientists use to evaluate light reflected off physical objects. “If one’s curious about having a rigorous definition of what is a medium roast, for example,” explains Ristenpart about standardizing roast level parameters. “Right now, one person’s dark roast can be lighter than somebody else’s dark roast. So it’s just chaos out there.”

Over 50 faculty members at the university are conducting coffee research, and the number keeps growing. During my tour, I was told about many more studies and projects. In the short term, the center must raise money to pay off the construction loan and fund student research.

Further in the future, the goals are to build a greenhouse and post-harvest station by the redwood grove, have a master’s degree program in coffee science, provide continuing education for industry professionals through the university’s Continuing and Professional Education arm, and be part of the larger global network of research stations.

Jenn Chen (@thejennchen) is an Editor At Large at Sprudge Media Network. Read more Jenn Chen on Sprudge.