Producer Diego Bermudez of Finca El Paraíso is no stranger to the world of high quality specialty coffee. His first major debut in the coffee industry came at the Cup of Excellence Colombia event in 2018. Although his coffee placed 10th in the competition, it fetched the highest auction price, at $54.10 per pound. This was no surprise to those fortunate enough to taste the lot.

This coffee was immediately recognized as something unique and rare—unlike anything else on the market at the time. (I count myself among the lucky ones who tried it.) The winning coffee, initially labeled as a Bourbon variety—though Bermudez later clarified it was a Castillo—was exceptionally clean, with a distinct peach aroma and flavor unmistakable to the nose, complemented by a creamy, lactic mouthfeel reminiscent of yogurt.

What followed was a natural evolution and a remarkable journey. In the years since, Bermudez’s coffees have grown in popularity and esteem across the global market for specialty, garnering features at noted roasters around the world including Manhattan Coffee Roasters (Rotterdam), Black & White Coffee (Durham), Lift Coffee (London), and many more. His work includes a range of varieties, from Castillo to Gesha and to Pink Bourbon. Yet, what sets them apart remains consistently the same: that distinct peach-like aroma, often paired with lactic acidity. If the classic gateway coffee for many first-time specialty coffee drinkers was once a natural Ethiopian with bursting blueberry flavors or a washed Ethiopian resembling elegant earl grey tea, Bermudez’s coffees from El Paraíso have redefined that entry point. Today, many people’s first unforgettable coffee experience comes from his farm, and cafes are clamoring to give that experience to their guests; a recent event at San Francisco’s noted The Coffee Movement highlighted the work of Diego Bermudez, with tickets that cost $100.

Diego Bermudez is credited with pioneering techniques like double anaerobic washing and thermal shock processing, methods that many farms in Colombia and beyond now emulate. Simply put, he is one of the most influential and genre-expanding coffee producers of his generation, with fans around the world, at every point in the coffee chain.

And now he’s embroiled in controversy.

Earlier this year, Bermudez announced a new initiative called Hachi Coffee Project in collaboration with Allan Hartmann, owner of Rocky Mountain Coffee in Panama, and Matheus Antonaci, managing director at INC Specialty. The three partners share responsibilities in an inclusive team structure. I had the opportunity to meet Bermudez and Antonaci during World of Coffee Copenhagen, where they launched a box set featuring six unique coffees. These included climate-resilient varieties like Parainema, as well as Pacamara and Gesha.

Then a few short weeks later, Hachi Coffee made international headlines when it was revealed one of their coffees had been disqualified from Best of Panama, an event created by the Specialty Coffee Association of Panama, which is part of the wider international Specialty Coffee Association (SCA). A coffee from this six-coffee set was tossed from the 2024 Best of Panama competition for being “altered from its natural DNA expression, with the intent to score higher and win by using foreign additives“—an accusation deemed an “attempt to cheat.”

Reader reaction on social media to Sprudge’s reporting on the controversy was loud, and opinions varied greatly. Some likened the use of co-fermentation to “performance enhancing drugs”—others suggested that the Cup of Excellence and Best of Panama were “afraid of progress.” Notably, several other high profile coffee producers in Panama took to social media to express their support for the disqualification. A few commenters expressed nuance and reason—a rarity on social media!—portraying the situation as a kind of double-edged sword: co-ferments bring more money to producers, which is good, but if more and more coffee is produced this way, what will happen to the classic coffees so many of us we love? Above all else this story became a referendum on how you feel, as a coffee drinker (and/or member of the coffee industry), about the growing prevalence of co-fermented coffee in the specialty coffee market.

In an exclusive interview with Sprudge, I was able to get the inside perspective from the team at Hachi Coffee Project themselves. It’s no surprise that they have a unique take on the controversy surrounding Best of Panama, but in my conversation with Bermudez and Antonaci, our discussion took an unexpected turn. The two founders shared their broader perspective and outlook on Hachi; despite Bermudez’s reputation as a processing wizard, the project is about far more than just innovative coffee processing. It explores uncharted territories in the specialty coffee industry, such as breeding and soil improvement—areas I believe are crucial for the future of sustainable coffee farming, with wide-reaching impacts that go far beyond the world of competitions and controversies.

This interview has been condensed for clarity. Since Bermudez and Antonaci spoke alternately and their roles at Hachi are indistinguishable, their responses have been combined into a single narrative.

Thank you for speaking with us—can you explain briefly the goals and aims of Hachi Coffee Project?

With the Hachi project, we’re striving to maximize the genetic expression of each variety. We believe the world is in constant change, and we need to go one step further to meet market demands. The future of the coffee industry lies in being able to anticipate and predict changing consumer tastes across different markets, while consistently generating new trends and attention. Our goal is to offer coffee enthusiasts products they’ve never tried before, creating new experiences.

First, our objective will always be to anticipate consumer preferences and stay ahead of the market by providing what people are looking for. We’re keeping our minds open as we design the path to achieve this objective. We believe coffee’s potential is still largely untapped—we’re still just at the beginning, still experimenting.

This summarizes our passion for coffee, but we want to emphasize that we’re not focusing solely on super specialty coffee. We aim to develop consistency and, most importantly, maintain high quality at much larger volumes.

Our second motivation was actually our primary goal with Hachi: it is to secure a genuinely sustainable future for coffee cultivation. There are countless challenges coffee farming is facing globally. As you might knew, according to some research, the regions most suitable for coffee cultivation could shrink by over 50% by 2050 under various climate scenarios. That raised a question: “Will there be enough coffee in the near future to meet global demand, especially high quality coffee?”

Also, during our work in Brazil studying Canephora coffee in the Amazon, we noticed a decline in overall coffee quality across many regions. Around the world, people often lament, “Panama Gesha isn’t the same as it was 10 years ago,” or, “The best coffee I ever had from Ethiopia was years ago, but yields have since dropped.”

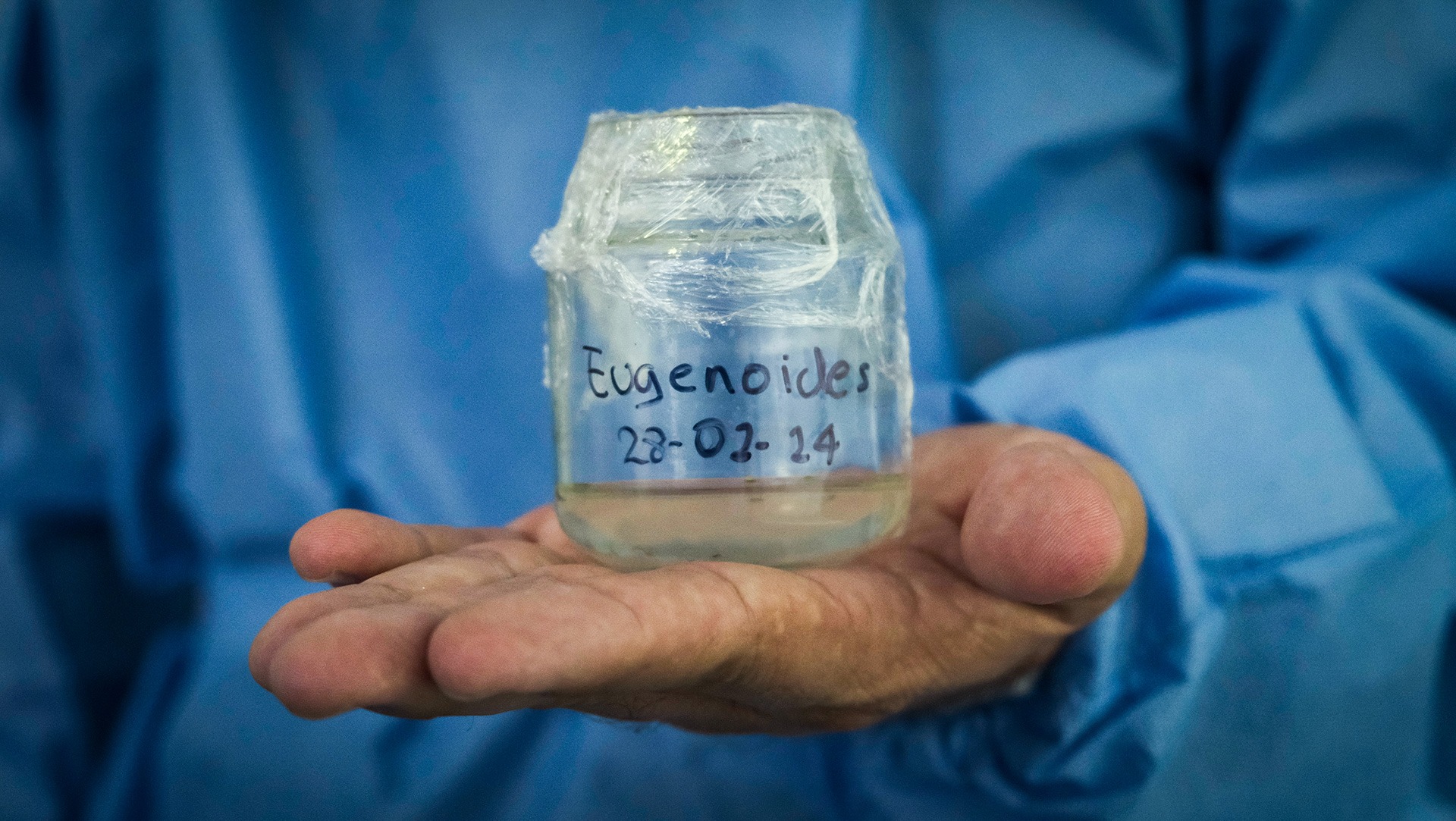

This decline isn’t unique to Brazil or Ethiopia—we’re seeing it here in Colombia too. So, to address both the coffee deficits and quality decline, what can we do? At Hachi, our chosen path to overcome these challenges is a biotechnology-driven project focusing on cloning, micrografting, and agroforestry to maximize the genetic potential of each coffee variety. Through cloning, we replicate identical copies of varieties with complete DNA integrity, preserving desirable traits and the genetic purity of the original cultivar. Simultaneously, we employ micrografting techniques to enhance crop characteristics, boost yields, improve nutritional content, and reduce pesticide usage. It’s important to emphasize that we aren’t solely focused on the super-specialty market—at Hachi, we want to make quality coffee accessible to everyone.

How does your approach at Hachi differ from your earlier work at El Paraiso?

Our approach with the Hachi project differs from what we did at El Paraíso. At El Paraíso, we used biocatalysis techniques to analyze the natural compounds in the coffee cherry, aiming to synthesize specific aromatic compounds through chemical reactions. This allowed us to create unique flavors by manipulating the coffee’s inherent properties. At Paraíso, our pursuit was always to avoid being dictated by the environment, we want to ensure that coffees harvested at different times of the year maintained the same sensory profile.

With Hachi, our goal is different. We want to bring out the full expression of each variety, making only subtle corrections to factors we believe might detract from cup quality. Take Parainema, for example. Many people don’t love Parainema due to its pronounced herbal notes, which can sometimes taste like bitter herbs or root beer. These flavors are intrinsic to the variety, but they aren’t always appealing to everyone. What we’re doing isn’t about eliminating these characteristics entirely; it’s about refining them—reducing the bitterness and making those herbal notes more pleasant, while still preserving the coffee’s unique identity. And one of our buyers—Prodigal Coffee, did a great job roasting it—the root beer flavor even transforms into something sweeter, almost like a soda.

For this Parainema, we used a biocirculation process. The coffee was washed and fermented submerged in water with mucilage from its own cherry. When we recirculate the mucilage, we enhance microbial activity, which consumes the sugars in the medium. This process naturally reduces the bitter and herbal flavors.

Interestingly, Parainema shares a compound with Gesha—linalool—which is responsible for floral notes. Just as you can reduce certain compounds during processing, you can enhance others. This compound is present in the cascara. In traditional washed processing, the cascara is discarded and plays no role. But all these aromatic compounds are there, waiting to be used.

So how do we bring these compounds to a washed coffee? We incorporate some of the cascara during the fermentation process. This is why most of our washed coffees are fermented submerged in water—it allows us to introduce cascara and transfer these beneficial compounds to the seed.

That’s how you process washed coffee. How about natural? If you want to preserve the original characteristics of the coffee, why produce natural coffee instead of just washed coffee?

Great question! If you take coffee from the same lot, process half as washed and half as natural, you’ll see that the coffee expresses itself in completely different ways due to the processing methods. With natural processing, the coffee stays in contact with the mucilage and cascara (the cherry skin) for a longer period, allowing the coffee to absorb more of the flavors and characteristics from the fruit itself.

But here’s the key: we want a cleaner natural coffee. One that retains the original characteristics but expresses them in a more elegant way. So, instead of just letting the natural fermentation process take its course, we enhance it with enzymes—something we’ve never done before at El Paraíso.

This is actually the first time we’ve processed coffees with enzymes, and it’s something unique to Hachi. We use two different enzymes: pectinase and glucosidase. Pectinase breaks down the pectin in the cascara, while glucosidase converts the mucilage into sugar to feed the microbes during fermentation. This approach speeds up fermentation by providing more nutrients for microbial growth and activity. As a result, we get a more expressive natural coffee that’s also cleaner because we don’t need to ferment it as long.

We also conducted an interesting experiment called the “microbiota” experiment. We took coffee from a single lot and divided it among five bioreactors. Each bioreactor underwent a different process based on the specific yeast strain we inoculated.

Even when using different strains of the same microorganism, all five coffees tasted distinctly different because each strain requires different nutrients and follows different metabolic pathways, leading to different reactions. Each strain reacts with different compounds, so it’s always about understanding the coffee you’re processing and what you want to extract from it—not altering its characteristics, but preserving or enhancing certain aspects.

You need to try different approaches to find what works best. The key indicator is the cherry’s taste—when you taste the coffee cherry, you identify the flavors you want to bring to the cup. This guides your approach to processing and experimentation. Success is achieved when the final cup tastes like what you first experienced in the cherry. That’s the fundamental idea.

Back in June of 2024, after the Best of Panama Association released news about some coffee being disqualified—many people learned that it was your coffee. People have only heard the association’s side of the story, but no one has heard from you. Would you like to say something about that?

We don’t depend on whether the Specialty Coffee Association of Panama agrees with our work or not. Honestly, we don’t rely on that for validation. I believe they fear change. And we don’t believe that engaging in debate is important for us.

How can you debate with someone who doesn’t understand what you’re developing? How can anyone claim we’re changing coffee DNA through fermentation? Instead of wasting time arguing with people who don’t understand what they’re talking about, we should use that time to promote what we’re actually doing with Hachi.

Many coffee connoisseurs know the truth about what happened, and that’s what’s most important to us. Rather than refuting their comments or fighting back, we’re focusing on continuing our work. We have our beliefs, and we’re showing the world the truth by giving them the ability to taste what we’re doing and draw their own conclusions. You can reach your own conclusions once you try the coffee. Truth always prevails. The best way to face a situation like this isn’t through argument, but by giving people real proof of what we’re doing.

The results speak for themselves. Just last month, Eric Chang won the National Barista Championship in Taiwan using our coffee. People from all over the world, from Asia to Europe to the U.S, are reaching out to us, wanting to try Hachi. We’re grateful that people didn’t turn their backs on us based on false accusations. Instead, they’re willing to try and offer our coffees, showing the world that the truth is deeper than what the media was saying.

This is a coffee project that wasn’t even launched nine months ago, and we’re already on many people’s minds and lips. I really believe that God’s timing is different from our timing—sometimes things speed up in ways we couldn’t imagine. We’re attracting attention from people who are interested in what we’re doing, and that’s been amazing. But we also know that when you bring change, you’ll always face resistance. So we’re grateful for how most people who are passionate about coffee and innovation are supporting us on this journey. With the support of the coffee community, we hope to continue showing the world a better future and new possibilities for coffee farming.

Is it correct to say that you refine and decide on a recipe for coffee fermentation?

What the market doesn’t understand is that processing protocols must constantly be adapted to the raw material we’re receiving—the quality of the cherries we’re processing. It’s never a static process.

The bioavailability of the compounds used in processing varies throughout the year. The soil is truly biodynamic. If you test soil samples every two months, you’ll see that each compound is in constant flux, and nutrient bioavailability shifts over time. So you can’t use the same process across different seasons of the year, since coffee processed two weeks after spring is different from coffee processed during winter, when the Brix have changed. You’re working with a living organism—it’s natural for things to change.

These changes affect the composition of organic compounds in the coffee cherry. Photosynthesis capacity also varies depending on planting distances between trees and varieties. Regional differences play a role too—everything affects the flavor. That’s why we need to continuously modify processing techniques to achieve desired results.

Achieving total control is impossible at this point. We can adapt processing techniques to reach a certain level of consistency, but fully replicating a specific profile is practically impossible, at least with current technology.

So, the processing approach at Hachi is like an amplifier—if you have coffee with four notes, you can choose which notes to enhance or decrease by playing with different microbes, right?

Exactly. You’ve got it. The goal is not to create entirely new flavors, but to amplify what’s already present in the coffee and make certain characteristics more or less expressive. For example, with Parainema, we focused on reducing its herbal bitterness and bringing out its more pleasant qualities. That’s a key part of our work at Hachi—recognizing the natural traits of each variety and enhancing them. It’s about being respectful to the coffee’s natural expression and how that changes with different growing conditions.

It’s the same approach for other varieties like Gesha or Castillo. Sometimes, the coffee surprises us because its inherent biological characteristics or environmental influences are unique. For instance, when we taste a cherry before processing, we’re often surprised by the flavors that emerge, which are the result of specific environmental conditions at that moment. From there, we can design a process to bring out those characteristics.

And we want people to experience the coffee just like the moment we first tasted the coffee cherries, so that’s why we are launching a project to start the roasting process at origin. There’s a big difference between offering fresh green coffee versus offering freshly roasted coffee at origin. That’s something we’re passionate about—demonstrating how roasting at origin can elevate the overall coffee experience.

Roasting at origin? Could you be more specific?

This idea first came up from a suggestion by Scott Rao.

People always talk about roast freshness but never about coffee freshness. How long ago was the coffee harvested? How long has it been sitting in warehouses in Europe, Asia, or the US? It’s overwhelming and sad for us when we export our best coffees and realize some of our customers aren’t storing them in appropriate conditions.

Sometimes we go to a coffee shop or event where someone approaches us with what they say is our coffee from a specific roaster. When we taste it, we find very old coffee with aged notes. We don’t recognize it as the coffee we created—there’s no correlation between what’s being presented and what we actually created for the market. We feel embarrassed, sometimes even ashamed, because of how the coffee is expressing itself.

We believe we can constantly improve our techniques to offer better coffee. Soon you’ll see what we’ve been working on—we’re launching a new coffee shop in the US. While it’s premature to share all the details, we want to see how customers react when they taste the best of our work directly from our hands—coffee that’s both grown and roasted at origin.

We believe coffee farmers can evolve beyond what the industry wants us to be—mere producers of raw materials. We believe there’s space in the market for farmers to touch other parts of the business, not just production.

It’s similar to winemaking. Think about it—if you wanted to drink good wine, imagine if winemakers only sold you the grapes and said, “Here, make your own wine.” What is unique about winemakers is that they produce the grapes, press them, ferment them, and bottle them—creating their expression of what the wine should taste like. In the coffee industry, we lack this experience because coffee producers can’t offer the final consumer the full experience. We can’t offer the product as we designed it.

Could you walk me through the other experiments you are trying to achieve with Hachi?

Sure. Instead of just focusing on processing, we decided to take a step back and look at the farming level. We wanted to improve coffee quality from the very beginning—literally from the seeds and plants themselves. This led us to start with biogenetic studies, creating cloning protocols, and conducting micro-grafting experiments.

So, basically we’re doing micro-grafting at the laboratory level, using culture medium to provide the perfect environment for plant growth. During the process, we discovered something interesting: some plants carry diseases internally without showing external symptoms, like fusarium fungi.

We’re working on developing antibiotic mediums to prevent these fungi from being passed down to the next generations. This way, we can have better plant material that won’t express these diseases in future generations.

And I think traditional breeding introduces too much genetic variability, so we are sticking with cloning. In my opinion, cloning is more predictable in preserving certain favorable traits. Through meticulous tissue culture techniques, we identify coffee plants with the highest genetic integrity and cup quality, then clone them. Cloning also saves time, since you don’t have to wait every crop year to take the seeds from coffee trees and replant them.

Another thing we are looking at is how we can use micro-grafting to develop more abundant root volume and secondary roots. This is important because we can generate better, deeper root systems that can access more nutrients and better express the variety characteristics we want. Right now, we’re seeing an increase in quaker beans worldwide, which is due to poor plant nutrition and the inability to absorb nutrients from different soils. This is compounded by climate change affecting wet and dry seasons globally.

While we don’t know exactly where this research will take us, we want to leave a lasting impact on regenerative coffee farming. We’re focused on long-term sustainability—not just solving today’s problems, but ensuring that future generations of coffee farmers have better tools to thrive. If we can find ways to grow quality coffee at lower altitudes, we’re not just helping ourselves—we’re helping the entire industry.

We’re also setting up a knowledge hub here in Colombia, where farmers, researchers, and industries can collaborate to foster innovation and share expertise. Our goal is to create a space where coffee farming evolves through shared learning and community-driven solutions.

People are very concerned about things like second-generation Gesha trees in Panama, but no one talks about soil analysis. How has the soil changed over the past 15 years? What was it like then? Nature is smarter than us, it evolves to adapt to its environment. The mutations we see in plants often result from changes in the soil, not just genetic selection.

Most farmers, particularly in places like Panama, only talk about altitude—claiming they can only produce good Gesha above certain elevations. But they’re not looking at how the soil has changed over the years or how we can work to provide the same environmental conditions we had 10-20 years ago. Instead of just looking for virgin soils, we need to improve the quality of existing soils and make them more suitable for specific varieties. Instead of just seeking higher elevations or focusing on varieties that demand those conditions, we need to adapt our techniques to regenerate coffee farming and produce excellent coffee at lower altitudes. The answer isn’t just finding new land to plant coffee—that’s actually creating new problems rather than solving existing ones.

Thank you.

Tung Nguyen is the founder of Citric Meets Malic and a Sprudge contributor based in Hanoi, Vietnam. Read more Tung Nguyen for Sprudge.

Photos provided by Hachi Coffee Project