What’s it like to do coffee business in a part of the United States facing especially massive challenges from Coronavirus?

For Florida cafe owners, selling coffee through a summer that’s seen COVID-19 cases skyrocket to the second-highest amount of cases in the nation has been a logistical—and sometimes ethical—challenge. Owners have questioned not only what model of business to operate, but whether they should be operating during a contagion spike at all. Some have closed for days at a time so that staff could be tested after a roommate was exposed. All have struggled with issues around Personal Protective Equipment, whether it be shortages for their own staff or buy-in from patrons on their safety measures.

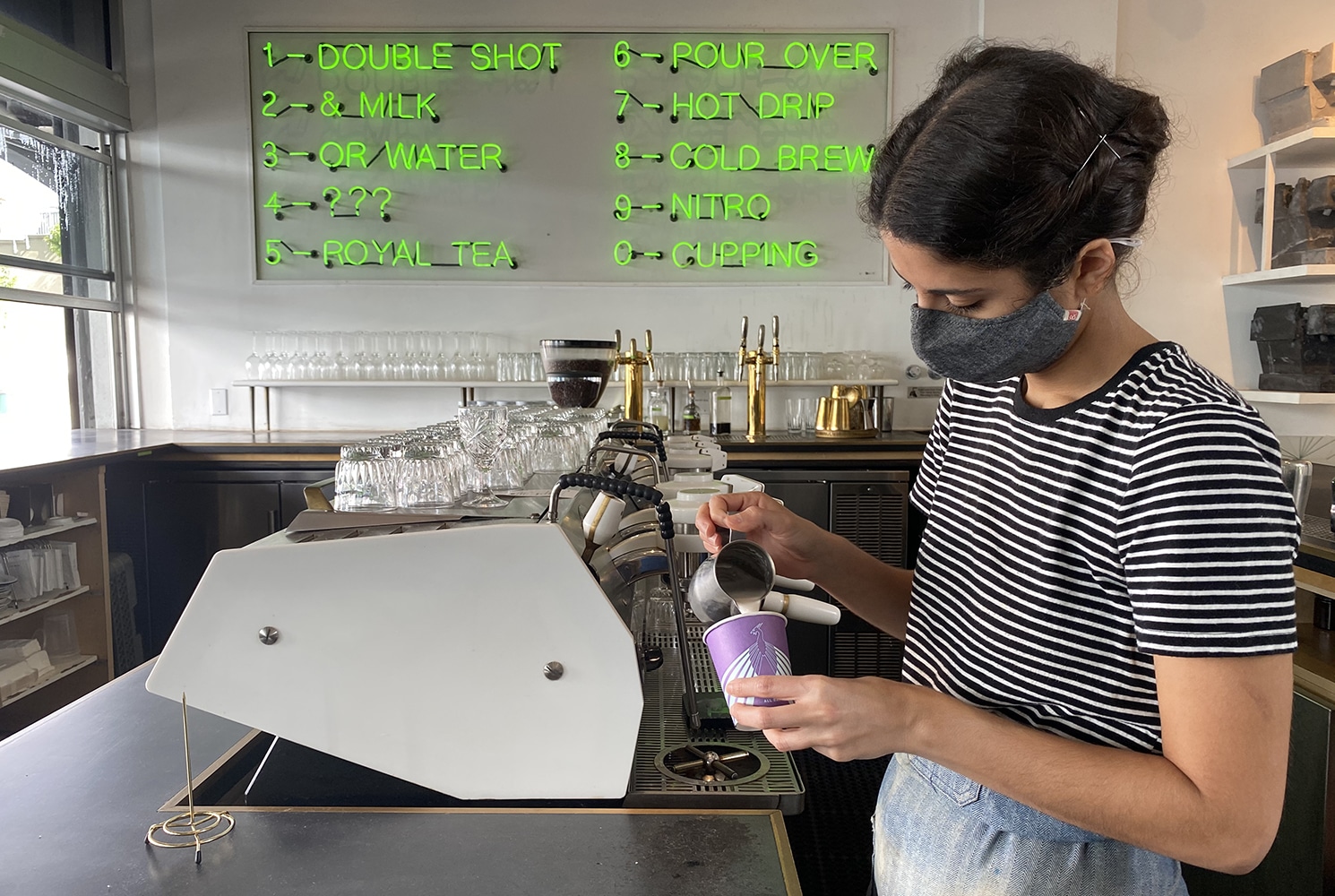

“Relative to Miami, we have pretty good compliance,” says Camila Ramos, founder of Miami’s ALL DAY. “But we still have signs saying stand here/don’t stand there, and people just don’t read them, educated or not. They don’t go to places looking to read stuff. So we do have issues like ‘Hey, you can’t stand there, hey, please don’t touch that.’ We also have a lot of guests that come up to us without masks, and we ask them to put on masks.” Sometimes, says Ramos, they’ve had to turn people away.

Ramos’ Miami neighbors at Panther Coffee have experienced the same, says co-founder Leticia Pollock. “Earlier in the year, there was more resistance to mask,” says Pollock—though masks are now mandated in Miami-Dade County. The resistance was “mostly non-verbal in the form of eye-rolls and pouting,” she added.

But potential attitude from customers hasn’t dampened owners’ commitment to safety. “My priority is our staff’s well-being and our community’s well being,” says Ramos. Most customers told to wear a mask will put it on without complaint or confrontation, she says. “For us, it’s like look, we’re just the messengers and we’re trying to keep things safe.”

ALL DAY, which operates a full kitchen as well as cafe service, found that in order to keep safe, it needed to change its service model.

“Even when we reopened for outdoor dining, I knew that the cafe model wasn’t going to work, having people coming up to the window and sit down at a table,” says Ramos. “The only way to get higher control of the environment was to have table service, so we have table service every day right now, which we’ve never had on weekdays,” says the former regional barista champion. It’s a lot of demand on her staff, Ramos says, which continues to operate as a smaller crew than pre-COVID times, to intentionally avoid being overstaffed.

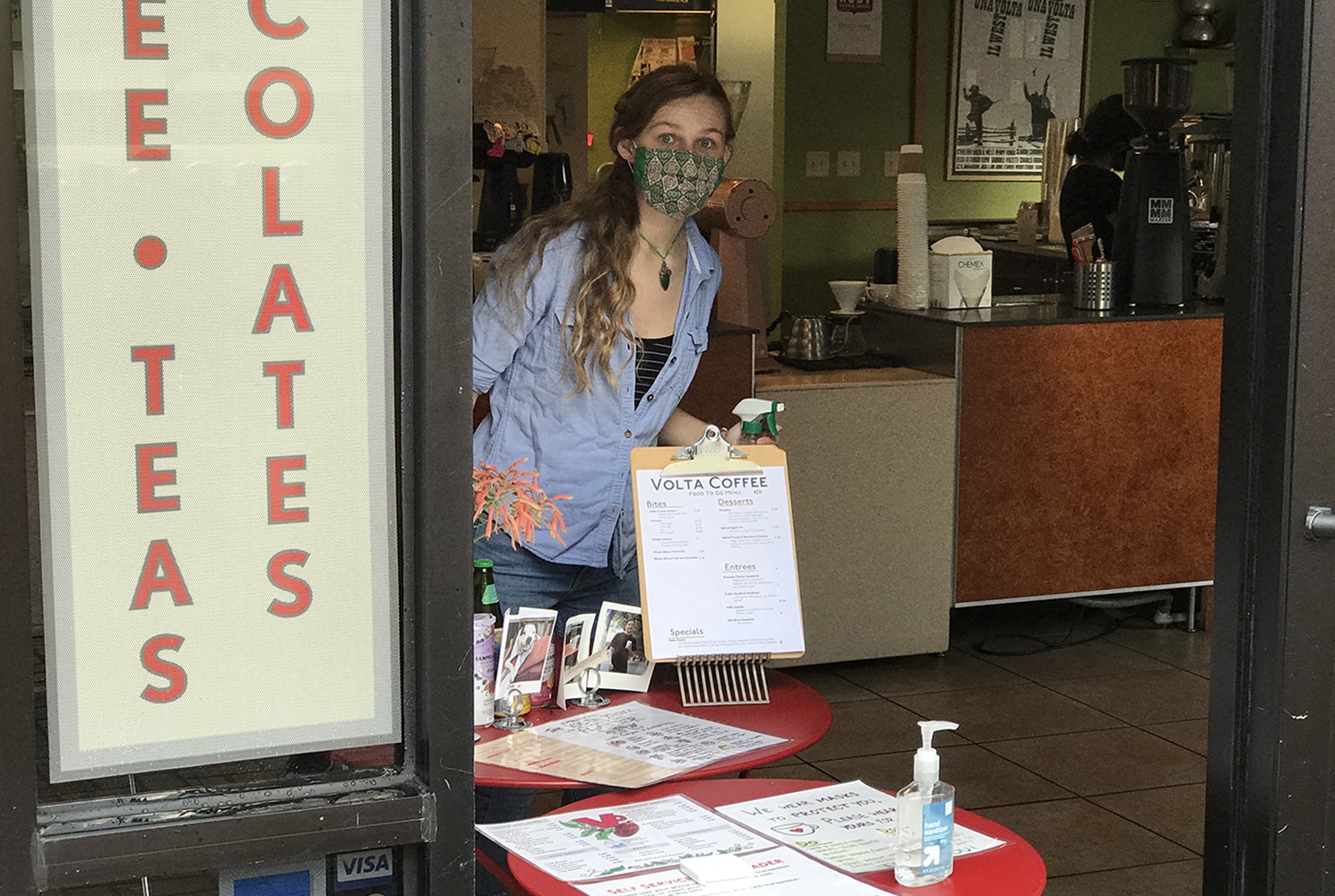

A few hours’ drive north in Gainesville, Volta Coffee owner Anthony Rue says his shop is one of the few remaining shops to resist reopening for inside customers. “It is starting to erode sales as people resign themselves to living with the plague,” says Rue.

Gainesville, a progressive city home to the University of Florida, has had comparatively low transmission rates to other cities, Rue says. “But we’re surrounded by the rest of Florida. You go down an hour south of us to Ocala and they literally get hostile if you walk into someplace wearing a mask. So you can’t fight that, and people will come to Gainesville to go to restaurants,” he says.

Business is down for everyone, of course, and in big college areas like Gainesville and Tallahassee, the end of summer portends both hope and fear.

“We’re a college town, and I’m not sure if summer’s actually slower than it has been, but we’re coming into a traditionally slow time with… a slow time,” says Jason Card, founder of Tallahassee’s Journeyman Coffee. Card was in the process of building out a cafe space within a new location of Ology Brewing Company when everything shut down, he says.

“Right now we’re not opening a cafe because it’s just weird and we’re not sure if it’s a good idea to do that or not,” Card tells me. “We’ve been working with roasters as a side project and selling coffee through our curbside with our beer. We’re trying to find something we can do that’s cool and fun and doesn’t involve a lot of people standing around in the same room.”

While the return of students might be a good thing for sales, says Rue, “Everyone is worried about what happens at the end of the month when UF students come back in force.”

Pollock and other cafe owners continue to wonder how long they’ll be able to juggle it all—the safety measures, the reduced income, and rollercoaster of trying to keep up with constantly shifting guidelines. “Regulations have fluctuated and changed incredibly often in South Florida,” says Panther’s Pollock. “Sales are down dramatically, and the inability to reach a significant lowering of fixed costs, especially rent, adds a layer of uncertainty to how much longer we can go on under these circumstances.”

Caroline Bell, co-owner of New York-based Cafe Grumpy, which also operates a store in Coral Gables, says they’ve had to roll with changes, including when it meant rolling things backward.

“We [reopened] with to-go at the door, and then we had people coming in. Some people weren’t coming in with masks, and then we went back to just at the door because since the cases started rising we thought to-go was better,” Bell says. Currently, her cafe in Miami is takeaway at the window only. (Even in now-comparatively-safer New York City, Cafe Grumpy is still takeaway-only as well.)

As with all things 2020, being adaptable to literally anything and everything seems to be the only option. Ramos concurs. “For me, my game plan has been and continues to be how to make the most socially conscious, best decisions with the information that we have available, and as the information changes being willing to adapt and change,” she says.

“Every time that the landscape changes, it’s like driving up a foggy mountain at night where you can only see the next three steps ahead of you. We want to be able to see daylight clear up the mountain, but we can’t.”

Liz Clayton is the associate editor at Sprudge Media Network and is based in New York City. Read more Liz Clayton on Sprudge.

Images courtesy Anthony Rue and ALL DAY.