Participating in an Ethiopian coffee ceremony is like standing in the front row of a live concert—but the band is the beverage itself. The nearly two-hour event draws your full attention, encompasses all your senses, and shuts out the outside world for the duration. It’s the coffee tradition of a place whose history with the drink goes back at least five times as long as it does in the US.

Ages before Starbucks was a household name, before coffee replaced tea as the drink of choice in America, Ethiopia brewed a culture of ritual around the roasting, steeping, and drinking of coffee. Kaldi, the young goat herder who, legend holds, discovered coffee after watching his goats frolic energetically following a snack on the fruit of a coffee shrub, is depicted on the country’s one Birr note (worth about a nickel). It is a part of the history, the culture, the economy, and, with its ceremony, the daily life of Ethiopia. With a barista in a uniform of flowing white cotton and the scents of frankincense and myrrh mingling with that of freshly roasted coffee, the multi-hour ritual might seem like a special occasion to an outsider. But in coffee’s native home, it’s simply the everyday manner of drinking it.

“The way we roast the beans, grind them in front of you,” explains restaurateur Tensay Assress of Little Ethiopia in Los Angeles, “this is the way to really try coffee the way it’s supposed to taste, the original bean, no machines involved. If someone is a coffee lover, this is the way to go about it.”

Ethiopian immigrants and their descendants in the United States have long kept up the tradition in their own homes, but many Ethiopian cafes and restaurants are pushing to introduce the tradition to new audiences. “It is our culture,” explains Assress, “in each household, every day. And we want to share that, the tradition and the culture.”

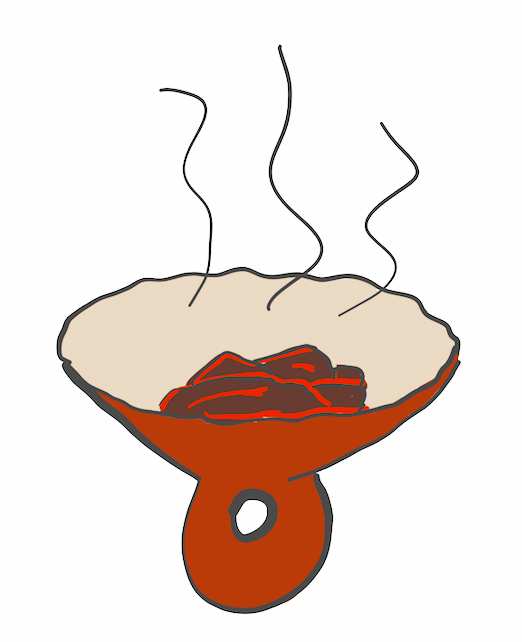

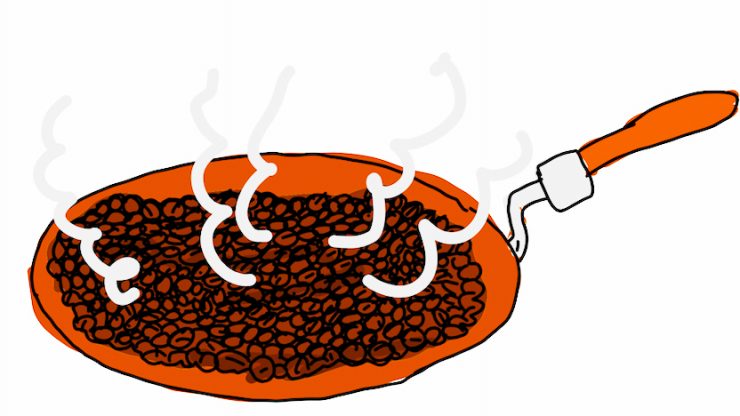

The first half hour of an Ethiopian coffee ceremony is an exercise in patience. Someone, usually a woman, washes and roasts the beans. They jingle in the pan, crackling as they take on color, the smell wafting upward with wisps of smoke, joining the nearby incense in perfuming the air. The barista, as it were, focuses on roasting the beans to medium, just enough to let the bright flavor, perhaps of blueberry, jump out from the cup. But not yet. First, the anticipation. Popcorn, dry-roasted barley, peanuts, or sunflower seeds make the rounds. Settle in, the snacks suggest—you’re not going anywhere for a while.

The ceremony takes about two hours from start to finish, beginning with the roasting in a flat pan over coals. Or, in the case of Martha Ayele, at her restaurant, named Jebena for the clay pot in which coffee is brewed, over a small gas stove. She uses a long, hooked tool to push the beans around in the pan, patiently waiting for the right sounds, smells, and appearance to indicate it’s time to remove them from the heat. Ayele does the ceremony at least once a day here, when business is slow. She sits down with her mother, who still scolds her if she tries to rush the roasting, asking “where do you want to go?” and they talk about “the past, the present, and the future.”

Much of the ceremony—for all its heavenly scented incense, flowing cloths, and clay pots—is all about just that: talking about your day, hearing the latest gossip, catching up with friends. At the end of the roasting process, Ayele adds a little bit of cardamom and clove. The ceremony, she says, “is about sharing our love, our lives.” The scent of hot coffee and spices joins the aroma of frankincense and myrrh, blossoming as the beans are ground, traditionally by mortar and pestle, before the hefty pile of coffee is dumped in the jebena.

Solomon Dubie learned to roast coffee at the age of eight. For Ethiopians, in America or at home, roasting green beans, grinding them by hand, and brewing them in the jebena is part of the everyday routine. It takes more than half an hour from the start of the ceremony to the first cup. “It’s all about the socializing,” he says. “Your saddest moments and your happiest moments, with your loved ones, with friends and strangers. Coffee is that ice-breaker. It’s the social norm. It’s every day.”

The grind on the beans can’t be too fine: the grounds go directly into the jebena, with cold water to brew. Tall, dark, skinny, the jebena bears a dancer’s elegance, drawn in part from its simplicity: there’s no straining process, other than the pot’s shape. The big bottom lets the grounds settle in and the thin spout keeps them from sludging forth.

A tray of cups sits in front of the barista on a low stool known as a rekbot, and that same thin spout pours from high above into the many cups below. Smooth and arcing, the coffee streams down like a caffeinated fountain. It is the first of three brew cycles, from which two cups per person are traditionally poured. It is the strongest of the three, called abol, and for that, Dubie named his Seattle coffee shop Cafe Avole.

Eventually, Dubie would like to roast beans at Avole, which also serves espresso and drip coffee, Ethiopian food, and American-style sandwiches. For now, he offers jebena on the menu. For $8, anyone can order the traditional Ethiopian brew—no ceremony, just an easy way to order coffee for a long conversation or perhaps for a group. If you finish the jebena, he will refill it with water, much as in the ceremony itself, where that second brewing is called tona. It’s slightly weaker, the same grounds swimming in new water.

The third and final brew, baraka, is the weakest of the brews, still the same grounds refreshed with more water. Sam Saverance, co-owner of New York’s Bunna Cafe, which offers weekly ceremonies and runs the website www.whatisthecoffeeceremony.com, emphasizes that the ritual isn’t actually that much about coffee anyway. “It’s the ambiance, it’s a constant thing you experience,” he says. “It becomes less about drinking coffee and more about becoming immersed in a sensory experience.”

The art of brewing and drinking coffee is all about finding the way to drink that fits your taste and style preference. With the fast-paced culture of the US, it’s unlikely we’ll see a renaissance of the Ethiopian ceremony—people setting aside two hours a day for socializing over coffee—and Dubie, Saverance, and Ayele all recognize that. But each has found a special way to bring Ethiopian-style coffee to the American way of life.

Ayele offers coffee to any diners in her restaurant while she conducts the ceremony, served in the same small ceramic cups used in the ceremony (free of charge—she’ll also conduct a full ceremony for guests by reservation for a fee). “I love customers, I love talking to people,” she says. It is that creation of community, that socialization, that has saved both her life and her livelihood—a customer who was a lawyer saved the restaurant when it was sued by a former investor, and another helped Ayele navigate the complex world of American healthcare as she got treatment for a medical crisis. With the ceremony, she says, she shares her love, “with family, friends, and customers.”

For Saverance, the ceremony is less about drinking coffee and more about becoming immersed in the sensory experience. Some people come just for the weekly ceremony, but most tack it onto the end of a meal. “It’s a snapshot of the culture in general,” he says of why it’s important to him to offer the ceremony. “Coffee has a very personal characteristic in Ethiopian culture—it’s the ambiance of the surroundings, the smell, it’s a constant thing you experience. There’s more of a personal relationship to the bean.” By opening the restaurant’s ceremonies to the public, he hopes to share Ethiopian coffee culture with more people.

Dubie takes it a step further, pragmatically extracting the coffee (and brewing method) from the ceremony: “You’ve got pour-over, you’ve got French press, you’ve got espresso, why shouldn’t you be able to go into a coffee shop and order a jebena?”

You can’t grab a jebena to-go at Avole, he points out (“If my mom says we’re going to have some coffee, it’s two hours. It’s not quick, it’s not a five-minute conversation, ever”), so serving coffee like this forces people to change how they drink it. “No worries, stress-free, relaxed. I want to bring that patient type of coffee into the shop,” he says, telling of a teacher who brings her students in to talk over a jebena, and of people driving in from the suburbs to relax over a pot.

Brewing coffee in a jebena is one of the oldest methods of making coffee, and participating in an Ethiopian coffee ceremony is one of the most generous, ritualistic ways to drink it. Bunna in Brooklyn, Little Ethiopia in Los Angeles, and Jebena and Avole in Seattle are each within a stone’s throw of some of America’s most cutting-edge, modern coffee shops, as are similar places in other cities with significant Ethiopian populations, such as Washington D.C. and Toronto. But in the shadows of the newest, hottest cafes, there’s a small group of Ethiopian restaurants and cafes who have figured out how to share their deep-rooted traditions in coffee. All they ask from the customers is to slow down a little and enjoy the ride.

Naomi Tomky (@gastrognome) is an award-winning freelance writing for The Stranger, Saveur, Lucky Peach, Tasting Table and more. This is Naomi Tomky’s first feature for Sprudge.