It’s been four years now, but I can still taste that first swig from an ice-cold bottle of Furlani wine.

Despite a slight breeze on my back porch that muggy Washington, DC evening, the mosquitoes were relentless as usual. While frantically scratching at our ankles, my wife and I shuffled back through the screen door into the kitchen and put the floor fan directly on top of the table in a last attempt to fend off the impenetrable humidity of a late August night. The bubbly alpine wine that I’d just brought back from Thirst Merchants in Brooklyn had been chilling in our makeshift bucket of ice and salt water for about 10 minutes—just long enough to get it frosty and mend our weary minds.

It was a post-fermentation blend of Müller Thurgau and Gewurztraminer entitled “Alpino Aromatico Macerato.” I had read that the grapes ferment in steel on the skins with no added yeasts, then go through a second fermentation in bottle, with no sulfites or dosaggio (the addition of a sugar solution or liqueur d’expedition to kickstart a second fermentation), capturing a natural effervescence in the final product.

The wine was blurry at first blush with some bigger pieces of sediment spiraling around in the glass, and its pét-nat-esque façade misled both of us to expect a little volatile acidity or barnyard bouquet—but it was so refreshing to find it so polished and welcoming on the nose. The aroma was frank and earnest, backed by potent wafts of pear, peeled apple, and citrus zest on occasion. One of its most noticeable and delightful features was a dense, calcareous minerality that magnifies both its complexity and drinkability.

Within seconds, each half-glass poured was a half-glass gone.

My wife was never a big wine lover and grew up in Milano on a healthy dose of spritz and table Prosecco, so I was accustomed to her maybe finishing one glass of my more particular wines at dinner just to humor me, but that night I watched in disbelief as she crushed half of the bottle beside me. Any variety of Furlani’s wines that we could get our hands on after that point would end up in our bellies, but the “AAM” became our ride-or-die table wine for any occasion. I couldn’t get enough of this wine’s versatility.

As fate would have it, we would meet its makers, Matteo and Annalisa Furlani, three years later at Vinello di Milano, one of our favorite natural wine bars on the fringe of Milan city, where they were hosting a tasting of all their available bottlings. The two of them were just as fun as their wines, so we ended up chatting with the Furlanis the rest of the evening and got an official invite, which we obviously accepted, to visit them in Trentino during their upcoming vendemmia (harvest), and even to participate in the grape rush for a few days.

The path to Trentino is always breathtaking: you drift through the lowest points of one narrow valley between the towering Dolomite mountains whose high jagged peaks never seem to stop converging on the horizon. Almost every bit of land you see besides rest stops and castles, from the edge of the autostrada to where the valleys ridge meets the steep limestone cliffs, is completely covered in vines.

The volcanic and dolomitic (limestone with high magnesium content) soils of the Trentino region have long been appreciated for yielding some of Italy’s finest wines, whereas the high-elevation vineyards surrounding the region’s capital city, Trento, are revered for contributing to some of the finest sparkling wines in the world. In fact, the spumante (foamy) wines made in the Trento DOC are not only made with similar grapes and in the same metodo classico process as Champagne, they’ve often been compared with the quality of the wines from Champagne.

Although he wasn’t the first sparkling winemaker in Trento, it was the legendary Giulio Ferrari who realized the potential of the region in the late 1800s and manifested the idea of making French bubbles in the Dolomites, before he labored to plant rooted cuttings of Chardonnay from France around the hills of Trento’s Lake Caldonazzo and launched his first vintage of alpine champagne in 1902. Much of Ferrari’s development and inspiration came from studies abroad, but he started his education at the San Michele all’Adige School of Agriculture of Trentino, the same university where Matteo Furlani studied oenology and agriculture many years later.

Like many young winemakers, Furlani admits he never envisioned a future working with his family amongst his hometown vines, but he decided after college to continue down that destined course of his family’s 280-year-old Trentino farming tradition. While he learned the land and the demands of field labor from his father Fabio who worked his entire life cultivating grapes and apples, he also found business inspiration from his grandfather Lido’s tenure in the hospitality and catering industry. Matteo Furlani rekindled this small part of his family history when he built a full-service agriturismo (farmstay B&B) in the early 2000’s near his birthplace, where guests can also purchase Matteo’s wines and Annalisa’s natural-wine-based cosmetic products.

Our journey to Cantina Furlani fell right in the middle of their weeklong harvest of Chardonnay grapes, which occupies almost half their entire harvest period. Matteo Furlani would wake up at 4:30 AM to work in the cellar, then help his mother Carla open up the kitchen of the agriturismo, or agritur’ as they call it. After each long day of collecting and dropping off grapes, he spent each evening working in the cellar and went to bed around midnight—so the only way to catch the full story was to try to keep up with him and stay in stride.

When we first arrived at the farm, Furlani was just backing up a Massey Ferguson tractor attached to a giant trailer filled to the brim with green glowing Chardonnay grapes. He wore a toothy grin, and even though it was already quite late in the afternoon, he greeted us without even a hint of fatigue. He apologized profusely for having so little time as he walked us around the corner of his property a little village circle to wash off his face in the central fountain. He pointed to an old man across the street on a blue skid-steer tractor that was dropping small loads of grapes into another larger trailer. “That’s my father Fabio over there; he’s unbelievable really,” he said, “and even at 73 years old, he still seems to work circles around the rest of us.”

Moving from the lower points of the vineyard to the highest, Fabio Furlani and his team of 13 pickers were clipping the grape bunches from their top stems into small handheld red containers, then depositing them into little crates between the vines. The biggest person in the group would then pass through the rows and collect each bin to pour into the loader of the blue tractor. When the loader was full, the elder Furlani would then drive it up the hill and deposit the grapes into the large trailer.

For a cantina as small as Furlani’s, I had to wonder where a harvest of Chardonnay this large was going. Matteo Furlani informed me later that evening that only 20% of their Chardonnay goes to his own production of Furlani wines, which is apparently quite common for smaller producers of the region. Because there are so many famous spumante producers with enormous cantinas within the region, the majority of these high-altitude Chardonnay grapes, like the ones grown by the Furlanis, get purchased by négociant merchants. This type of extra income from these negociant sales can offer a huge net of financial security to small organic producers that would typically have to maintain higher bottle prices to compensate for common production losses like vine diseases or bacterial contaminations in fermentation.

The Chardonnay grapes that Furlani sells to negociants are the same organically grown grapes that go into his own line of Chardonnay. Beyond their vast array of rainbow-colored sparkling “surli” wines made in the metodo ancestrale that you most likely will find at your local natural wine shop, Furlani also makes a resounding Champagne-style Spumante Metodo Classico Brut with their chardonnay and pinot nero as well as white and rosé versions of their Spumante Metodo Interrotto Brut Nature, in which the wine goes through the same vintage approved Champagne-style traditional method of resting the wine on the lees in bottle for 24 months—except in the case of this “interrupted method,” the bottles don’t get disgorged.

The Furlanis’ spumantes were actually the wines that set the stage for what became their extensive (and growing) bottling list. They started to organize and prepare in 1998 by producing 1,000 trial bottles a year of the Spumante Metodo Classico Brut, and would release their first vintage of 3,000 bottles in 2004. Four years later, they introduced their line of surli wines, started working with natural wine organizations, and have since brought their annual production up to an impressive 40,000 bottles.

A cinematic 20-minute descent to the cellars ran through zigzagging roads dotted with tiny alpine villages landmarked by a single espresso bar and church, then led us back up to the gradual ascent to the Furlanis’ cellar at 2,362 feet. Turning off the last main road, the experience couldn’t have been more perfectly pastoral as we drove into a dense uphill labyrinth of cornfields and fruit orchards that the fleeting sunlight could scarcely illuminate. As soon as we started moving uphill, the temperature instantly dropped. Trentino’s perfect climate for moderating fermentation and growing grapes, in a nutshell.

Tucked into the rain shadow of a looming rocky peak, the cantina is attached to the Furlanis’ home, with the spread of their vineyards uphill to the left, and downhill to the right their apple and cherry orchards. Annalisa Furlani was playing in the yard with their son Eduardo, and as she warmly greeted us, Matteo emerged from the cantina smiling but still appearing concerned about all he had yet to do.

He picked up Eduardo, led us into the cantina. I couldn’t help but notice how organized and clean the space was, especially considering they were in the middle of harvest. Smacking one of eight pallets near the entrance, Matteo said proudly, “These six here are going out to our importers in the United States, Selectionaturel, and one pallet each of the other two to the UK and Denmark.” He showed us that on his bottles, he doesn’t label their organic certification except, by customer request on the bottles going to Denmark. “We have the certification, which is important to us,” he said, “but there is a small charge per labeled bottle to the organization, so I prefer to only label when necessary.”

Eduardo, feeling slightly shy, ran off and hid in an empty steel fermentation tank while his father went through his process of monitoring fermentation with us. “The first grapes of the year that we harvest are our Müller Thurgau, and these five tanks are filled with them from three different days of vendemmia, and so they’re in three different stages of fermentation,” he said while placing his hand on the side of the tank labeled with the date 27-8. “You can feel this one is hotter than the other tanks because it’s from the most recent date of that grape’s vendemmia.” As fermentation does generate heat, the steel was indeed hot to my touch. “Just yesterday, the tank was so warm that the fermentation foam bubbled out the top like a pot of pasta,” he said with a chuckle, “and so I needed to remove some of the wine and place them in these little damigiane (demijohns) to keep it from overflowing.”

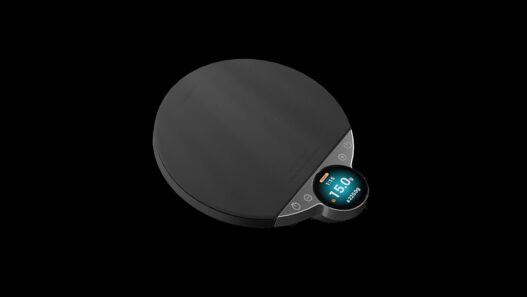

“I monitor each tank every morning and every night,” he told us. As a part of his nightly rounds, Furlani then started to show us how he tests the sugar content of the wine with a basic hydrometer, and then uses it in an equation to determine the potential alcohol content in the wine. “This one is only at about 7%,” he said while writing the rough percentage on a chalkboard attached to the tank, “and in a few days it will be ready at 11%.”

Depending on the grape, the fermentation time varies from seven to 10 days. Once each tank is finished, they remove the skins with an electronic press then blend each tank of the same grape type into larger outside steel tanks to mature and settle until February or March when they then bottle all of the wines to prepare for a second fermentation in the bottle.

When asked what he does with the skins, he replied with his grin, “We make grappa, of course!”

The next morning, we went down to the first floor of the agritur’, and Furlani’s mother Carla, who was managing the dining floor, was setting out a mouthwatering buffet of warm cakes and fresh fruits for the guests. Furlani arrived soon thereafter and made us both cappuccinos that we knocked back quickly so we could rush out the door with him before 7:20 AM.

Furlani used to start harvest earlier in the day, but recently a few new residents moved into the local borgo (village), and filed complaints with the authorities against the noise from tractors and equipment early in the morning. “Vineyards have been growing in this region for thousands of years,” he said with one hand gripping the steering wheel and one gesturing his words, “and then people move here just two years ago to escape the sounds of the city to live in the silence of the vines, but forgetting that a vineyard is also an active farm.”

We were joining him on his morning route of inspecting ripeness levels of all his nearby vineyards in the town of Povo. Slightly higher up the mountain from where the team was harvesting the day before, we stopped at Furlani’s vineyard that was divided by Chardonnay at the top, Müller-Thurgau in the middle, and Pinot Nero at the lowest section. He explained that although they had a Müller-Thurgau harvest already, this vineyard is at a higher altitude and requires more ripening time.

As we transitioned from the rows of Chardonnay to the Müller-Thurgau, Matteo demonstrated how he can tell the difference between the two types of grapevines by the veins in their leaves. We kept in a hurry down towards the Pinot Nero vines because he was predominantly preoccupied with them due to potentially drastic ripening conditions.

“During this time, I have to watch the weather channel every morning to keep the Pinot from swelling and bursting,” he explained, “ and if they predict storms will come through the area, I have to rush the whole team to harvest right away.”

Pinot Nero can also be a particularly difficult grape to manage for Furlani because of funguses like Botrytis cinerea. The grapes are tightly bound together in their clusters, so if the fungus attacks one grape, it can easily attack the entire bunch. “When the Müller-Thurgau gets affected it’s very easy to just pick out the affected part of the cluster before it spreads,” he said, “but this is very rarely the case for Pinot Nero.”

Apparently most of the winemakers in the region use chemical fungicides to treat their vine fungus complications, but because organic fungicides and planetary elements like copper are unable to treat or prevent botrytis, Furlani combats the fungus with meticulous canopy management and the regional method of raising vines in a “Pergola Trentino.” This type of trellis creates a spacious grape canopy and offers plenty of space between rows for improved airflow.

There are several EU-approved organic insecticides that Furlani has had to use in the past, but he expresses an obvious discontent with having to do so. “Treating the vines is not just a health risk for the vines, my workers and my family because we live and work here on the farm,” he explained, “but it’s also a financial cost that I’d also prefer not to have… the tractor, the labor and the treatment itself is quite expensive!” He waved his hand to follow him back up to the truck and continued, “My health too would be better if I didn’t breath in traces of the sulfur that we spray,” then adding, “even though it’s an approved organic and biodynamic treatment.” (I appreciated that he touched on this subject because it often seems to me that there’s a common consumer misconception that practicing biodynamic agriculture is all butterflies and neem oil.)

“There’s a balance for all of this,” he said, “when the grapes arrive in my cellar, they have a beautiful and clean skin, and a nice perfume. It’s very important because I never add sulfites in the cellar, and the wines will develop problems later if there are problems with the grape skins.”

Despite its difficult demeanor, Furlani claims the Pinot Nero as his favorite grape variety.

“I just love it in all of its royalty,” he said with a sigh, “it’s the queen for the Chardonnay, and adds long life to our region’s spumante.” In reference to cantinas such as Franz Haas, Kurtatsch, and Tramin, Furlani stated with certainty that some of the most elegant Pinot Noir in the world is grown in Trentino—Alto Adige/Südtirol. “If I had my choice I would grow as much Pinot Noir as we do the Chardonnay,” he said, “but it’s very risky for me to harvest it for more than one or two days because of the rains.”

We hopped back into the truck and drove a few minutes uphill through patches of fog towards one of Furlani’s highest vineyards to check the Müller-Thurgau that will be last in line to harvest. At the top, he pointed out that the mountain over Povo looks like a sleeping giant and started musing about the rich heritage of this area while inspecting the seafoam green grapes. He clapped his hands abruptly and exclaimed, “Are you ready to pick some,” then hushing himself to a whisper as it wasn’t yet 8:00, “are you ready to pick some grapes?”

On our last evening in Trentino, the Furlanis invited us to come for dinner at the cantina. While Matteo went to clean up for dinner, and Annalisa was busy in the kitchen. Eduardo was assigned the task to take us on our final tour of the vineyards uphill from the house. Joannita is the only grape being grown near the cellar, and it all goes into their cult-favorite bottling, “Joanizza.” The obscure German grape is a fungus- and disease-resistant cross between Riesling, Seyve-Villard, Rulander and Gutedel, and was used predominantly as a wine blending grape in its time.

Annalisa took an aperitivo break to join us outside, opening a bottle of their blend of indigenous white grapes called “Alpino”. Matteo joined us with several bottles to pair with the multiple course meal his wife had prepared. In the midst of being completely blown away by their genuine hospitality, wild charisma, and the delicious food, Matteo passed an unlabelled bottle to Annalisa to open. From the cork, I could tell right away it was one of their mountain Champagnes. It was from a 0/0 sulfur limited bottling of their Spumante Metodo Classico Brut Riserva, still on the lees, and it seemed to pour into my glass in super slow motion to Teddy Pendergrass in the background. Luscious, thick and golden; it was irresistible. On the nose: fresh apple pie, candied ginger, the rich aroma from the caldarroste (carts that roast chestnuts in the street). Bubbling tiny pearls across the tongue, it overflows the mouth with a foamy wash of ripe fruit and honey as dense as the night air of DC in August.

The last wine that they opened that evening was the same “Alpino Aromatico Macerato” that we had tried four years before in DC, and here on this cool Trentino night, I felt the rush of those moments where everything has come full circle.

Alexander Gable (@mrgable) is a freelance journalist based in Milan. Read more Alexander Gable for Sprudge Wine.