After three days of hyper-caffeination at the first-ever Milan Coffee Festival, it was a relief to escape the crowds for a quick trip out to the quiet and often foggy rural town of Binasco. I was traveling in the opposite direction of traffic—to take a private tour of Gruppo Cimbali’s historic espresso machine factory and MUMAC Cultural Center.

MUMAC stands for Museo della Macchina per Caffe and is home to a collaborative collection of over 300 professional coffee machines that span more than 100 years of innovation. Attached to the Cimbali factory, it’s the largest espresso machine museum in the world.

This converted spare-parts warehouse wasn’t solely intended for the means of meandering through history. The MUMAC Museum opened in 2012, and as part of their ongoing push into the specialty coffee market, Cimbali opened MUMAC Academy in 2014 with the idea of building a space to host certified coffee education programs, events, and coffee competitions. With third wave coffee still somewhat nascent in Italy, every espresso machine manufacturer seems eager to open their own academy and museum, and I was eager to see the Cimbali facilities, which are among the first.

The town center of Binasco is about a 20 minute drive southwest of Milan towards Pavia, and is ornamented with all of the classic Italian landmarks you come to expect no matter how tiny the town: a macelleria (butcher shop), a pasticceria (pastry shop), a tabaccheria (tobbaconist) with an espresso bar and of course, a photogenic medieval castle near the square illuminated by overarching Christmas lights sprawling down the main street.

Gruppo Cimbali SpA relocated its headquarters from within the center of Milan to Binasco in the 60s and has since been the largest employer of its residents. An employee base of around 450 people is distributed between the logistical hub in Binasco and their three production facilities in nearby cities Bergamo and Cremona.

The 200 employees that work in their facilities can produce up to a stunning 200 mechanical appliances a day (not just espresso machines). While we were suiting up with steel toes and hard hats for the factory tour, Cimbali’s Production Manager Paolo Molteni explained that this level of efficiency is attributed to his implementation of the “Lean Manufacturing” system.

Lean Manufacturing is a philosophical and methodological system that comes from the automotive industry that when it works as intended, produces perfect products on time through minimization of actions that don’t add value to the process. This type of development doesn’t just happen overnight, Molteni explains. “The involvement of our original factory operators was fundamental when we started this journey a few years ago.”

The facility was empty, dark, and silent while the operators were on lunch break. As we passed through the assembly rows, I noticed that the lights automatically illuminated only the stations we were standing in, prompting the many questions I had for Molteni about how Cimbali was combating production waste and energy consumption.

Molteni attributes the “Lean” system as a key factor in energy reduction in all of the facilities. The factories are partially powered by solar energy, and with recent renovations like a geothermal floor heating system, conversion to all LED lighting, and new cooling systems, Cimbali has brought overall energy consumption from production down 10% in the past year. 12% of that overall consumption is powered by renewable energy sources, and hazardous materials from production have been reduced to less than 1% of the company’s overall waste.

As the factory started to fill back in with employees, I slipped out of my safety gear and took off towards the undulating facade of the imperial red MUMAC Museum building. We were greeted by technology specialist Filippo Mazzoni near the gift shop and reception before making our way over to the lobby cafe for some mid-morning macchiatos.

In addition to his quirky and talkative manner, Mazzoni’s years of experience as a trainer and technician for Cimbali makes him an engaging tour guide. He popped open antique machines left and right throughout the museum to explain the evolution of coffee tech and made sure to squeeze in plenty of juicy details on historic patent drama between rivaling machine manufacturers (some of which are now owned by the same parent companies).

The majority of pieces on display are restored and owned by espresso machine collector Enrico Maltoni. Maltoni discussed a shared vision of a museum likes this with Maurizio Cimbali when they met in the early 90s, and the two have worked together towards realizing this dream ever since.

Each of the six chronological galleries in the museum represents a different era of technology, all adorned with Maltoni’s collector coffee cups, magazines, and other signs of the times. Although the museum is without question a Gruppo Cimbali venture, there are machines on display by virtually every company from La Marzocco and Kees van der Westen to Elektra and Vibiemme.

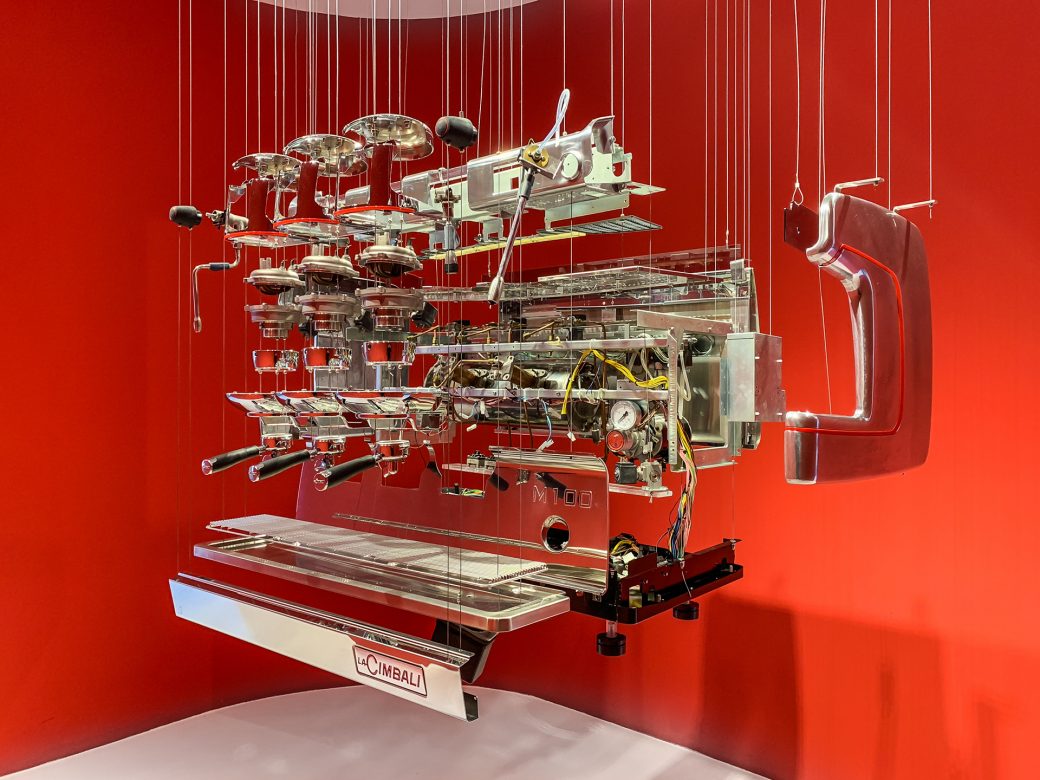

The final exhibit of the museum was a personal highlight, and featured the only machine on exhibit that Mazzoni couldn’t open up for a photo; the exploded view of a La Cimbali M100, seen at the top of this story.

We then made our way to the MUMAC Academy. The two-story SCA Premier Campus features a barista and technician training center and water lab on the first floor, and a sensory lab on the top floor that regularly hosts CQI certification courses. (Thankfully there were only a few minutes to breeze through the museum library, because I would have been fixated for hours on its collection of over 15,000 patents and coffee reference points dating back to the 16th century.)

In a town of about seven thousand people, only a quick drive from one of the largest metropolitan cities in the world, the MUMAC Academy protects and valorizes the history and culture of coffee machines with a dedicated focus on technology and the future of the industry.

From humble roots in a Milanese copper shop in 1912 to becoming one of the world leaders in the production of high-quality espresso machines, I was impressed by their ability to stand firmly by their integrity, humility, and glocal modus operandi.

Alexander Gable (@mrgable) is a freelance journalist based in Milan. Read more Alexander Gable for Sprudge.