Famed Loire Valley winemaker Pascal Potaire is the mind behind Les Capriades, a line of pet-nat wines that have helped inspire global interest in the humble fizzing form. But Potaire has long had another love on the horizon. That would be Poiré—the sparkling pear counterpart to apple cider—but it wasn’t until last year that pears came into his life in a very real way. “I’d been interested in poiré for a long time,” Potaire explains, “whenever I would taste a poiré I found them elegant and pure and incredibly intriguing.”

After five years of discussing a prospective pear project with friends and contacts in the Vendôme area, Potaire’s pear plan began to take shape. Conversations with chef Guillaume Focault of the restaurant Pertica led to a fortuitous connection with Foucault’s cousin, Estelle Mulowsky, in 2018. A pear enterprise was born.

Potaire learned from Foucault and Mulowsky that the Northern reaches of the Loir-et-Cher region, where grapevines yield to fields of grain and scattered orchards, is rich with fruit trees but poor in producers. This left room for interested parties to get a hold of heirloom apples and pears as well as promote local products and regional specialties that had been long forgotten.

Mulowsky, who raises Percheron horses in the countryside near Vendôme, noticed during her strolls with the workhorses that several orphaned orchards and pear and apple trees were producing fruit that simply fell from their branches and went to waste every year. Mulowsky was looking for a way to salvage the fruits, which brought her to the door of Pascal Potaire and the Domaine des Capriades. Pascal expressed his interest in making poiré at his winery and the two came up with a plan: Mulowsky would assemble a team to harvest the pears and Potaire would buy them and make poiré alongside his range of world renown pétillant naturel.

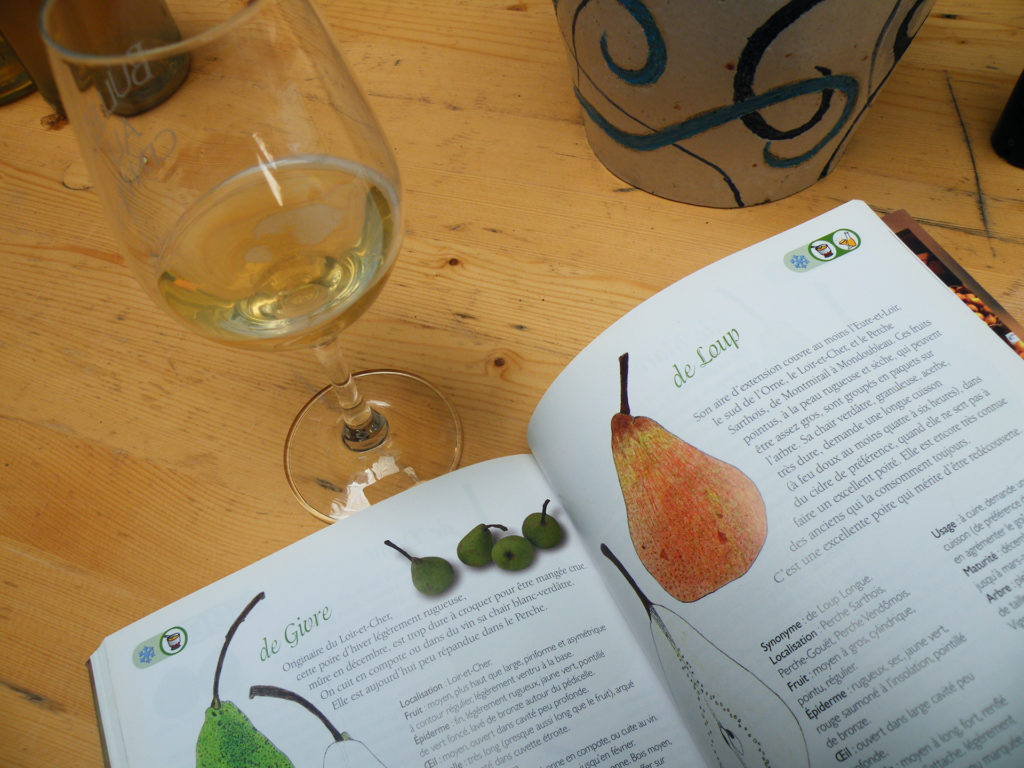

During the 2018 harvest, while Potaire and his associate Moses Gadouche were managing the grape harvest, Mulkowsky led a small team in gleaning unidentified varieties of pears. Potaire, who was newly equipped with a mill and press adapted for processing the fruit, awaited the delivery with excitement. He wasn’t sure what to expect from the process; “it’s like working with a grape varietal I’ve never used,” he told me at his cellar in Faverolles-sur-Cher as he disgorged bottles of poiré in various states of fermentation. Potaire, as always, was humbly underestimating the scale of this venture—not only was he working with a variety of fruit he had never vinified, he was working with varieties that no one had vinified. His only guide in the process was an independently published 20-year-old book on the subject entitled, Pommes et Poires du Perche, an illustrated guide that he referenced frequently during our conversation.

The result of this pilot year in poiré production is three distinct vintages, separated by pear variety to the best of the book and Potaire’s ability. Using this sole resource and visual cues, Potaire identified three main pear varieties; Carési, Crasseau Rouge, and Poire de Loup.

Part of the fun of the process has been deciphering what types of pears were included in last year’s harvest haul. Discovering each variety means also discovering its story. The Poire de Loup, Potaire learned, was also known as the “champagne of pears” and had been used surreptitiously during less productive years in the process of making champagne in order to increase volume while escaping the consumer’s attention.

This bit of historical pear trivia supports Potaire’s conviction that poiré’s similarity to wine makes it “an absolute intermediary between the apple and grape.” Whereas traditional French cider remains rustic and a clear by-product of the pomme, the pear base equivalent transcends its origins and becomes more and more complex over time.

During the process of making poiré Potaire noticed several overlaps between pears and grapes. The role of terroir and the age of the plant was striking, especially when Pascal discovered the impressive lifespan of pear trees, which can live—and produce—for over 200 years. “The interest in working with trees that can live for decades—even centuries—is that we can truly explore a notion of terroir,” Potaire explains. Tasting the three vintages—none of which will be ready for another year at least—you can already pick up notes typically associated with wine: pear, of course, but also a crisp and fresh acidity found in schist-forward Chenins found in the Poire de Loup vintage. Notes of tarte tatin and baked crust, similar to orange wines and aged reds, are present in the Crasseau Rouge cuvée.

Ciders and poiré are largely underestimated and looked at with a pejorative eye, according to Potaire. There is also the fact that pears remain an unappealing option for producers looking to turn a profit. Despite their long life, pear trees often only give a significant amount of fruit every other year. The pear is also more sensitive than the apple and has a tendency to turn volatile during fermentation. The nature of the pear makes it less economically interesting to turn into a fermented drink and therefore for every apple orchard in France you’ll find only a handful of pear trees. Potaire experienced this reality first hand in his first year of production—hoping to make only poiré he ended up working with almost as many apples as pears since the pear harvest was less than expected. After bottling, Potaire counts 400 bottles of cider against about 650 bottles of poiré.

Regardless of the economic uncertainty of producing poiré, Le Domaine des Capriades is excited to integrate this new venture into their family of pétillants. In addition to participating in the development of a new image of poiré and cider, Potaire hopes that the undertaking will also help take the edge off financial concerns surrounding the increasingly present threat of frost in the vines. “Making poiré is also a way for us to overcome some of the economic losses associated with frost,” Potaire explains, adding his voice to an increasingly common discussion among winemakers about how to diversify their activity in order to continue making wine in the face of frost.

While environmental factors weigh heavily on the hearts of all winemakers, Potaire seems more interested in the pursuit of the perfect poiré than in its potential profitabilty. These first batches will be allowed to ferment in peace until Potaire deems them ready to meet the world. Having said that, Potaire hinted that visitors to Bulles au Centre—a pétillant tasting that Potaire and Gadouche have organized every summer for the past six years—might get a chance to try the winery’s newest additions. You may even try them without even knowing it—as Potaire playfully suggested he might slip the poiré in his lineup of pétillant naturel and see how many discerning palates can tell the difference.

Emily Dilling is a freelance journalist and based in the Loire Valley.