At the end of January, Paris hosted the second Le Carnaval du Cafe (LCDC), an event put together by Collaborative Coffee Source (CCS), a Norway-based coffee importer. It was an ambitious two day event packed full of presentations and cuppings, with Monday devoted to Africa and Tuesday devoted to South and Central America. The list of speakers included, among others, longtime coffee professional Paul Songer, author Oliver Strand, scientist Flavio M. Borém, and researcher and leader of the team of scientists that mapped the coffee genome, Philippe Lashermes.

With coffee, it’s easy to just focus on taste, but that’s just one part of the story. Events like LCDC focus instead on coffee’s political, technical/scientific, and cultural levels, bringing together roasters, buyers, farmers, millers, exporters, and importers to learn more about coffee. LCDC is “current, not boilerplate,” Oliver Strand told me.

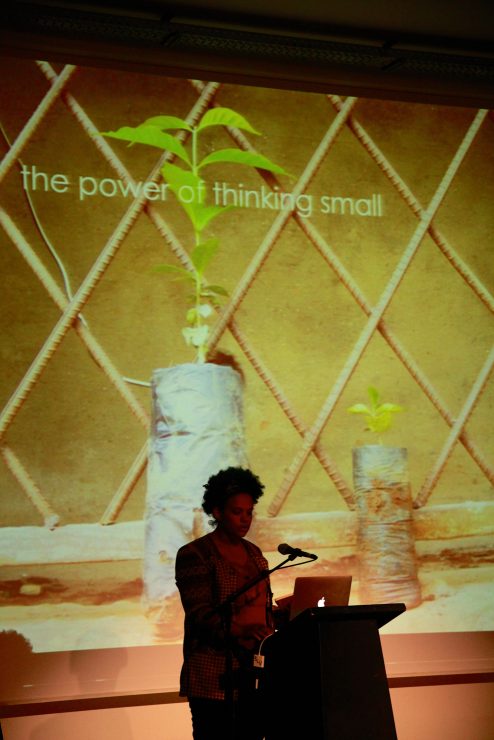

So what’s current? We were treated to Strand reading a section about Kenya from his forthcoming book; Carlos Arévalo of La Palma y El Tucan in Colombia sharing insight on the Castillo hybrid coffee variety; a lot of talk about roya and potato defect, including a scientific analysis of potato defect issues by Paul Songer and an inspiring presentation on “integrated pest management” by Lauren Rosenberg, who is working on her PhD in sustainable development and works with the Long Miles Project in Burundi.

As Songer pointed out, “the next problem for coffee may be evolving somewhere as we speak,” which made Lashermes’ presentation on the coffee genome all the more poignant: the better we understand coffee the better we may be able to treat the things that threaten it. There is definitely room for a better link to be made between coffee research and practical application, with the goal of translating research into tangible action items.

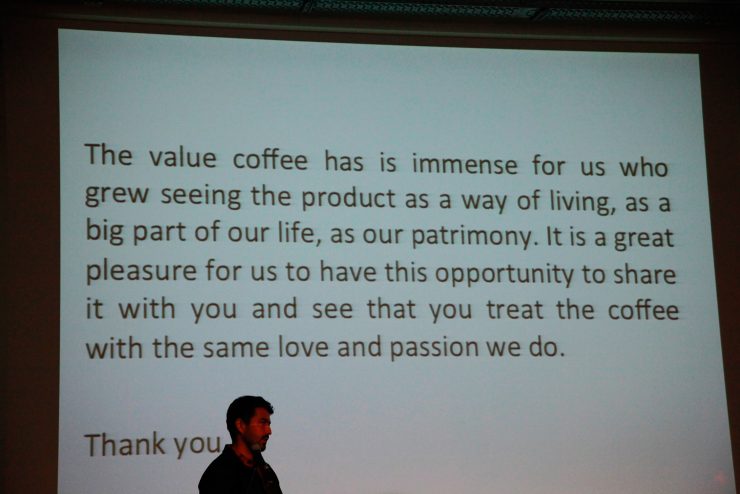

On the cultural side, Heleanna Georgalis gave insight into the Ethiopian market, having us cup eight different coffees roasted just a few days before in Addis Ababa. LCDC Farmer of Honor Miguel Moreno also shared his very personal story, translated from Spanish by Honduran exporter Benjamin Paz, who pointed out that for over 100,000 families in Honduras, just like for Moreno, coffee is their livelihood.

If LCDC highlighted anything to me, it’s that for the vast majority of people, taste is the only real focus when it comes to coffee. There is a continued disconnect that most in the general public, and sometimes even within the industry, have towards the nature of coffee production. As Rosenberg so eloquently put it, “I will never know what it’s like to own a piece of land as my only bank account.”

The high-end specialty coffee industry is built on the assumption that quality is economically fruitful. The idea is that higher quality means higher prices paid to importers, which in turns mean that hopefully producers are able to make more money for their harvests than before.

But this all takes hard work on both sides of the spectrum. “Specialty coffee is manmade,” Thoresen said. “it takes ambition… then it takes meticulous craftsmanship.” As such, we can’t just come to the table with just expectations of quality, because this ignores the many axis on which coffee sits, its intersecting political, technical, and cultural implications. “We have to find a balance between the expectations of the buyer and the socio-economic realities of the producers,” said Arévalo.

That livelihood is hard to remember when you are staring at a wall of coffee beans, trying to decide whether you want a Kenyan or a Costa Rican. In the food world, if we choose to buy local, we can easily shake the hand of a farmer. When your coffee producer is on the other side of the world that becomes a whole lot more complicated.

On the Saturday before the event, I attended at cupping at Belleville. The roastery had offered up the opportunity to their regular customers to come and meet Moreno, who happens to be the brother of Jesus Moreno, whose coffee anchored Belleville’s original offerings sheet. It was my first time meeting a coffee producer; unless they are deeply embedded in the coffee industry, even the most avid of coffee consumer may never have the opportunity to travel to a country of origin to meet the people that grow, harvest, and process their beans. To have the consumer, the coffee roaster, the coffee buyer, and the coffee producer all in the same room was a pretty unique experience for me, and one I won’t forget soon.

Rosenberg said something that has stuck with me since Monday. “There are huge problems in Burundi,” she said. And what do huge problems do? They can easily make us feel intimidated, that we are too small or insignificant to deal with them. “But hopelessness is a lie and you should never deny the dream of small beginnings.”

Maybe coffee is a small thing for most people—the thing that doesn’t get a second thought—but its impacts are huge. LCDC and events like it that bring this massive global supply chain together are a reminder that there is no room for hopelessness; only discussion that leads to paving a sustainable path that leads us all, consumers, roasters, buyers, exporters, and producers, forward.

Anna Brones (@annabrones) is a Sprudge.com desk writer based in Paris, and the founder of Foodie Underground. Read more Anna Brones on Sprudge.