Many in the natural wine world are, in a sense, waiting for the apocalypse: the moment the very notion of natural wine becomes distorted and mainstreamed into oblivion.

When, four years ago, the opening of Williamsburg’s The Four Horsemen was announced, people could have been forgiven for thinking that moment had arrived. The restaurant and wine bar made big news in all the major food publications (plus Pitchfork), chiefly because one of its four principals is James Murphy of the band LCD Soundsystem. If natural wine in America was ready for the main stage, as it were, this seemed to be its chance.

Instead, the Four Horsemen turned out to be no more and no less than an intimate, characterful restaurant with a devoted staff and a big, mostly natural wine list. At 950 square feet, its size is normal for Paris, but small for New York—and for the US at large, almost a blip. If the restaurant is nonetheless distinguished on a national level by its keen sensibility for natural wine culture, credit must go to co-founder Justin Chearno, a veteran NYC wine guy whose background in natural wine goes back to the earliest-whispered appearances of the phrase in US wine circles in the early 2000’s.

Chearno is late 40s and bespectacled, with a crescent of wavy auburn hair. By turns deadpan and enthused, he resembles a tax attorney who has discovered the secrets of alchemy. Before—and during—his career in wine, he played guitar for DC noise-rock band Pitchblende and later in instrumental rock outfit Turing Machine, which first brought him into James Murphy’s orbit. The two met in 1998, when Chearno was looking for someone to produce the first Turing Machine album.

Later, from 2002 to 2012, Chearno worked as the buyer for influential Williamsburg wine shop UVA, where in 2008 his path crossed with that of the natural wine importer Zev Rovine. “I was trying to sell him wine,” Rovine recalls. “I had just started Zev Rovine Selections and he bought some stuff. But then he offered me a job. I worked weekends at UVA for three years for extra dough while my company was getting going.”

Rovine explains that it was Chearno who introduced him to the thriving Paris natural wine scene. “He brought me to Le Verre Volé, Le Chateaubriand, etc. We drank a million bottles. I think it’s fair to say Justin introduced me to natural wine as a whole.”

In an interesting twist of fate, after leaving Uva, Chearno would go to work for Rovine in 2013. It would keep him traveling regularly throughout the wine regions of France and Italy for the next five years.

Chearno and his eventual partners in the Four Horsemen—Murphy, Christina Topsoe, and Randy Moon—had long entertained the idea of opening a restaurant. “Because the place we wanted to go didn’t exist in New York,” says Chearno, who during his travels to Paris had become enamored of the ambience of natural wine destinations like the aforementioned Le Verre Volé, Aux Deux Amis, and Racines. Murphy and Topsoe in turn cite Tokyo’s Ahiru Store and Copenhagen’s Ved Straden as inspirations. Chearno credits Moon with bringing in the influence of the versatile, welcoming service style of Australian cafe culture.

“When James and Christina found out about the space possibly being available in a year or so, we all agreed right away,” Chearno recalls. “But it turned out the space was going to be available immediately and we had to get our act together pretty quickly.”

The Four Horsemen opened its doors quickly, then, in summer 2015, with Chearno still working full-time for Zev Rovine Selections. The mainstream food press descended, as did anyone who cared about wine in New York. The apocalypse didn’t come to pass. This past September, Chearno left his job working for Rovine to devote his attention entirely to the Four Horsemen wine program.

“It got to the point where the restaurant was doing well enough, and the wine program had gotten serious enough, that it was like, either I do it or somebody else does it,” he says.

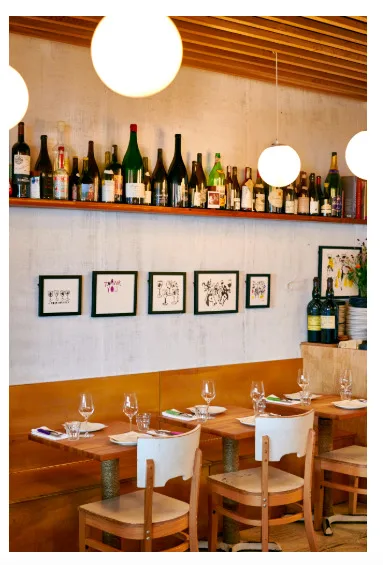

Today the restaurant—which seats 40—routinely does 200 covers throughout a Friday evening service. The bar area’s 16 seats host a wide cast of industry regulars and young Brooklynites, all surprisingly attentive to the novella-length wine list, and the bartenders’ hyper-informed disquisitions on the glass-pours. In the dimly-lit dining room beyond reigns a relative calm, generally attributed to the owners’ heightened attention to acoustics. Pale wooden slats span sections of the walls and ceiling in an effect reminiscent of Aesop skincare boutiques. In the rear kitchen, chef Nick Curtola—formerly of Park Slope pizza and wine destination Franny’s—plates a menu where Parisian cave-à-manger staples (local cheeses, charcuterie) and Spanish bar snacks (olives, pane con tomate) share billing with lamb sausage, beef tartare, and a crudo selection worthy of Venice.

Floating between the Four Horsemen’s two service areas on any given night is Amanda Spina, the restaurant’s cobalt-eyed general manager who’s been responsible, over the years, for promoting and translating Chearno’s ambitious wine program to Brooklyn diners each night.

“His enthusiasm and energy are hard to match,” she says of Chearno. “He is the ultimate record store nerd about this stuff. He is curious and excited—always—and that is contagious.”

We had a few words with Chearno about his view of wine from the vantage point of The Four Horsemen, four years in.

Did you have any founding precepts for the wine list at The Four Horsemen?

I wanted to open with a list that could make people happy, where we represented the growers and the wines that we loved. But I made a real effort to avoid anything with exceedingly high levels of volatile acidity. And I didn’t want anything mousy. I wanted everything to be really clean. And it was interesting that some of the pushback we got initially from guests was they wanted wines that were a little more adventurous.

Did that surprise you?

I was nervous about [serving these wines in] a restaurant. In retail [at UVA], I was not afraid at all to stock natural wines that I enjoyed, at least conceptually, because that person took that wine home and dealt with it. But I was very nervous about some of those wines getting opened in front of the guests. And it turned out that people were way more open than I was.

So over time there are things that I’ve added to the list that I still think are really good wines, but aren’t necessarily something I would take home. I still don’t want any mousy wine. But it’s been cool to broaden sort of my standards.

Do you have any redlines in terms of winemaking practices?

I really don’t want any wines that are yeasted. And I try my best. But sometimes we get some older things that are really interesting, like some old Bordeaux or something like that, that’s just fun to have. And I feel like some of those things get to stand alone. If you can offer it at a great price, and it’s an important wine from a great vintage, it’s a fun thing to do.

I don’t want to argue; I don’t want to fight with anyone about anything. I just want to pour great things that get people excited.

Do you find it hard to get enough volume, stocking mostly natural wine?

One of the issues is that everything is allocated, right? To some degree it’s a false scarcity. There’s sort of a demand that’s created, and everybody panics, and everybody takes their wine, and then it sits on their lists or in their shops forever. All the time I see wines that people freaked out over, and it was like, “Get it now or you’re never gonna get it!” You get your three bottles and then I see those three bottles in some retail shops for a year.

The buzz exists within the buyers and the owners and the wine directors. But often the buzz doesn’t exist with the guest or with the retail client.

One thing that we’ve been doing, that a lot of people can’t afford to do, is we’ve started off-site storage. So I’ve started putting a lot of things away.

What makes a wine list interesting in New York City right now?

I do think a place is interesting if they’re just gonna sell Pierre Beauger and Bruno Schueller, and like all those sort of out-there wines—the free jazz part of the list. If they stick with it and they believe in it, that’s great. That’s a point of view.

What we try to do—which is key for us, in terms of staff retention—is to be able to sell something like Cornas, and sell something like Michel Guignier. And be able to sell Babass alongside like Conterno or Rinaldi.

We like to be able to tell both those stories, and have people come in and be able to participate in your restaurant, without feeling excluded. I think it’s really funny when very serious classical wine people come in, and they realize they can spend the evening drinking Rinaldi or Clape and be perfectly happy. That’s exciting to them. And those people often return more than the naturalistas.

Have you felt a change in clients’ attitudes towards natural wine since opening?

People still come in every day and say, “So what is orange wine?” That’s the really really really big one that drives people crazy. I’m still getting calls for articles on orange wine in fashion magazines.

The one I hate more than anything is that person who drops themselves down on the bar and says, “I want your most fucked-up wine that tastes like horses’ blankets.” That’s really short-sighted wine tourism. When people say, “Let’s go to that place and drink fucked up wine, and when we want to drink real wine we’ll go somewhere else.”

Even though we opened only four years ago, time moves exponentially fast in the natural wine world. Things have really flown by. At the time there weren’t as many importers. It’s crazy how many more wines are coming in now than there were then.

How many selections is the list now? Are there any underrated sections that people ought to pay more attention to?

I think it’s 650 selections. It really does ebb and flow.

I was really lucky to go to Austria this year. And I feel like this year there will be more dedication to finding more expressive wines from Central Europe. There’s a lot of great winemaking there, and I was really surprised with how much I connected with it, a lot more than I thought I would.

And I love Beaujolais so much. It’s fascinating to me, just 15 years ago, Beaujolais was the cool kid wine. And the generation below me now is like, “Wow, you drink Beaujolais huh? That’s crazy, it’s not really my thing.”

What’s the biggest misconception about the restaurant people have before they visit?

We fucked up when we opened and we kept calling it a wine bar. We were talking in the Danish or Parisian sense of a restaurant. Not Bar Veloce, where you come in and get prosciutto and cheese, and then you leave. So it was tough on the chef and his team, because for years people were just [talking about a] wine bar—wine wine wine wine!—and they weren’t talking about the food and the kitchen. We were naive in thinking that that was okay. So now we make sure we always say wine bar and restaurant, and it’s definitely made a difference.

But when we opened, we definitely had people making a reservation that would arrive, and order salumi and cheese and have a glass of wine each. A lot of people didn’t understand what we were when we opened. I think because of James Murphy’s involvement people expected that we were going to be a party disco natural wine bar. And we wanted to be a serious restaurant that had great wine and great service. So people thought we were a little stiff.

How is creative input divided at the restaurant? Has any one horseman proposed an idea that was shot down by other three horsemen?

Most of the great ideas are shot down by stupid laws in New York City from the Dept. of Health. It would be great to do grilling in the kitchen, but you can’t have open fires. There are lots of technical things like that that drive us crazy.

But overall we’re pretty much all in the same boat. We try to find solutions to things that don’t cost us a million dollars. You can solve anything with money, but we have to find ways to solve things conscientiously because we’re small.

No one who ever opened a restaurant before would have taken that space as a restaurant. Every single one of our friends who had restaurants said, “You guys are going to die, this is a terrible idea.” But we believed in it.

Thank you.