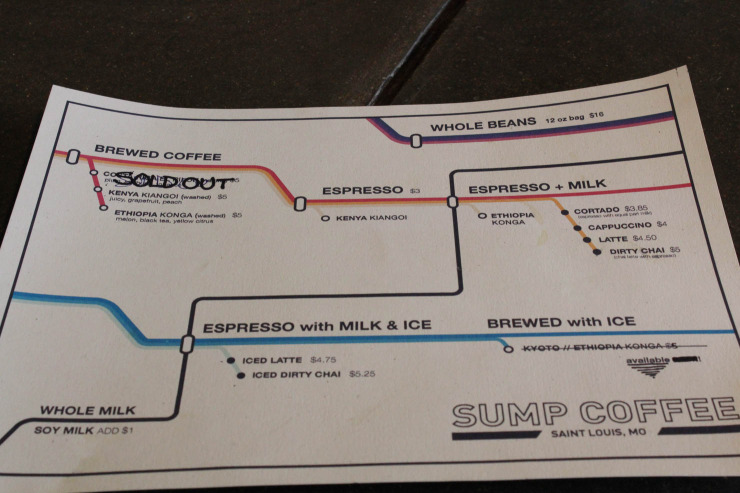

It’s a busy Saturday morning at Sump Coffee in South St. Louis City. A line forms behind a single paper menu that masquerades as a subway map. A brief synopsis is provided, and the customer places an order. No payment is collected. Instead, a single page of paper tracks the order. A Hario v60 pour-over bar with front row seating for three occupies the main room’s far side adjacent to a wall adorned with the company’s notorious bearded skull and crossed portafilter and coffee leaf logo.

Past two Steampunk Brewers and three Kyoto cold coffee drippers, a first-edition Slayer Espresso machine greets guests as it is worked in tandem. As one barista steadily pulls an espresso shot and pours everything into the awaiting vessel, the other churns a pitcher of milk into a maelstrom. Before finishing the espresso with velvety steamed milk, the cup is eyed up like a PGA golfer putting for the green jacket on the 18th hole of Augusta National. The drinkable masterpiece is framed on a saucer and raced to the patient consumer. The process quickly starts again; six more cups await their turn.

Amidst all of this, owner Scott Carey is diligently attending to Sump’s latest roast. He’s equipped with a stopwatch and pen. Every 30 to 60 seconds, he marks and tracks pre-established parameters to ensure a consistent roast every time. Everything Sump roasts comes from the hand of Carey and in his compact 2.5 kg Diedrich roaster. The machine has already logged over 13,000 roast hours since July 2012.

“We try and be peak-to-peak or seasonal roasting,” Carey says. “What we try and do is buy coffees that are going to be more fruit-forward. We typically like to buy higher elevation coffees and we roast, it’s popular to say but I guess we roast to what we believe is a Nordic style.” In terms of what that actually means for their coffees, Carey says, “what we’re going for is cup clarity, brightness by sourcing the coffee’s opening fruit, and what we sacrifice is body or really the bigger notes you develop from as you push that Maillard [caramelization] reaction in the drum. Lighter, brighter, cleaner, fruitier, that’s what we’re trying to do, and then when we brew or when we present the coffee, that’s what we’re trying to highlight. It’s this idea that hopefully, if we present a cup that’s clean and clarified, that it will demonstrate where that cup is from and how that cup was processed.”

Prior to owning and operating a cafe and roastery in his native St. Louis, Carey worked as a patent attorney in New York City. A visit to Ninth Street Espresso’s Alphabet City location around 2006 altered his trajectory and the way he looked at coffee.

“I remember that first experience,” Carey says. “The barista’s name was Bob. He was from Portland. He was grumpy. There was nobody in there. He had a bunch of sailor tattoos. I got [a latte] to go and I remember he put it on the counter, didn’t smile, didn’t say enjoy, didn’t say anything. He put the lid next to it and I looked down, I looked up and I was just like ‘Did you just do this?’

Carey says he looked for elevated coffee experiences with his girlfriend, Mars Yamaguchi, on the weekends, but would soon have to put his growing coffee interest on hold. Carey travelled, and eventually relocated, back to St. Louis to take care of his brother Jeff. Jeff had been diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a bone and soft tissue cancer. Scott took care of Jeff, and when he wasn’t helping his brother, he checked out local coffee spots in his hometown.

“There was coffee, but it wasn’t like what’s been happening in the last three years in St. Louis,” Carey says. “Out of my own hubris or arrogance, I thought I could create what was happening in New York essentially here.”

Scott closed on a building at 3700 South Jefferson on October 10, 2011. Jeff passed away nine days later. Scott completed the build-out with his brother’s tools, each marked with Jeff’s nickname: Gypsy.

Sump Coffee opened for business December 1, 2011 as a multi-roaster cafe, but decided to explore roasting when consistency of product became an issue. A roaster was bought in July 2012 as Carey learned roasting on the fly; he says over 60 kilograms of green coffee were practice roasted before going out to customers.

“This idea of finding your own voice and creating that voice and throwing it into the pile, that’s when roasting became like ‘Oh we should start doing this, we should think about this,'” he says. “It gives us control of what we have even though we didn’t know what we were doing, but it also allows us a voice or a dialogue in a greater landscape.”

Sump Coffee has a spartan set-up, similar to the shops Carey frequented in New York City. No cream or sugar station. No decaf. A dirty chai is the only remaining ode to the second wave of coffee. Two milk choices exist: whole and soy. Ideally, Carey would only serve whole milk.

“In a way it’s a little bit like Fight Club,” he says. “There’s a little bit of confrontation, but we try and do it in a way that’s not arrogant. We try and say ‘Essentially what I want you to experience is something that you may not even know was possible in coffee.’ That’s how the dialogue begins, ‘Just give it a try.’…I use this analogy over and over: We don’t make a Hershey bar, which is a modern feat of food engineering. We make single estate chocolate bars. We’re trying to highlight where that coffee came from, how it’s processed and that seasonality.”

What does Sump Coffee have on tap for the coming year? Carey says installing a new 12-kilo Diedrich roaster is at the top of the list.

“We always want to be pushing the envelope and reevaluating what it is we’re doing,” Carey says. “We’d like to get that new roaster hooked up and see where we can go from there, but buy good green coffee and continue to build the brand and create an exceptional experience for the people who enjoy what we do.”

Evan C. Jones is a Sprudge.com contributor based in St. Louis. Read more Evan C. Jones on Sprudge.