I almost didn’t write this piece on impostor syndrome. Ironically, signs of it flared up as I was researching and writing. I thought: “Anyone can write this piece, why me?” and “I’m going to collect 15 research articles when two would’ve been fine.” These symptoms of doubting, overpreparation, and feelings of not being good enough were echoed throughout my interviews with coffee professionals.

Barista Emily* (not her real name) suffers from impostor syndrome. When she serves customers, “I never think that the drinks I’m putting out are good,” she says. “It doesn’t matter how well I dial in. I’m never happy with it.” Even with positive feedback, she often thinks to herself that the drink “could be better” and that “someone has pulled this coffee better” than she has.

Barista trainer Sandra* echoes Emily’s sentiments. Despite her 15 years in the industry, she says, “I still find myself feeling out of place, like I still have to prove myself.” Even with her positive encouragement from her support circle, she’ll find herself thinking, “My closest friends, my colleagues—they’re just saying nice things that make me feel better.”

These feelings can be easily brushed off as nerves or a lack of self-confidence. Instead, they paint a larger picture of those who deal with impostor syndrome.

Dr. Kevin Cokley is the director of The Institute for Urban Policy Research & Analysis at the University of Texas at Austin and a professor of Counseling Psychology, and African and African Diaspora Studies. He’s quick to correct me, pointing out that impostor syndrome is not a medical diagnosis. Instead, “impostor phenomenon” or “impostorism” is used instead in research papers.

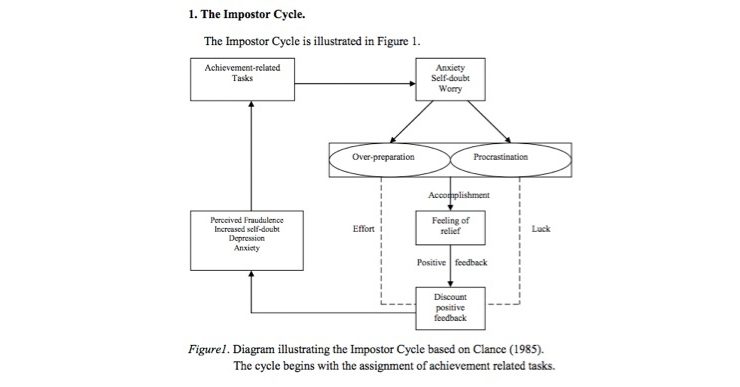

He describes “impostorism” as “feeling like you are fooling people when you have achieved some level of competence in your given profession or in the classroom. In spite of all indicators that would suggest that you are an accomplished person.”

Impostorism can manifest in a professional environment as someone attributing their success to luck or feeling like a project they undertook wasn’t as well executed, despite the praise they might receive.

Dr. Cokley’s research on impostorism centers around the psychological impact of gender stigma and race in college students. He notes that “impostorism is very much prevalent among students of color” and muses that ethnic minorities may be more susceptible to feeling like an impostor when “they’re in spaces that are predominantly white.”

Dee, a customer representative at a coffee company, agrees. She says, “My impostor syndrome is very much rooted in being a woman of color. All of your mistakes are amplified as bigger and for a longer time.” To combat the feelings, she over-prepares for her projects, adding, “it’s why I’m very thorough and very into details.”

Dee, a customer representative at a coffee company, agrees. She says, “My impostor syndrome is very much rooted in being a woman of color. All of your mistakes are amplified as bigger and for a longer time.” To combat the feelings, she over-prepares for her projects, adding, “it’s why I’m very thorough and very into details.”

After obtaining her current position, she discovered who her competition had been—some were well-known coffee professionals with more experience than she has. She confessed, “I definitely have moments of ‘Why me?'”

Contrary to the initial research that gave impostor syndrome its name, studies have shown that gender does not play a significant role in those who deal with impostor feelings. In fact, 70% of the population is estimated to have feelings of impostorism at some point in their lives. These feelings are often more prevalent among high-achieving individuals with a streak of perfectionism.

One of the ways that one can work with the feelings of impostorism, says Dr. Cokley, is to “have a working environment where people feel comfortable sharing one’s sort of vulnerability.” Having open conversations about these feelings is important, especially when they’re coming from industry professionals who have achieved a high level of success.

David Buehrer, co-owner of Houston’s Greenway Coffee, confesses he didn’t know what impostor syndrome was until I asked him if he ever ran into these feelings as a business owner.

In examining how he operates Greenway, Buehrer realized he has a deep-seated fear of rejection and peer comparison, both signs of impostorism. He intentionally does not have a sales team, because he never wants to be compared to another coffee roaster on the shelf. “It fundamentally changed our operations because we just never wanted to have that experience of rejection,” he says with a laugh. This fear has “1000% indefinitely stunted [our] growth.”

Another key strategy in preventing the feelings from spiraling into anxiety and depression is to build a strong support network.

Bethany Hargrove, a barista at Wrecking Ball Coffee in San Francisco, placed fourth in the 2017 qualifying barista competition in Knoxville, and fifth nationally at the 2017 US Barista Championship in Seattle. She says she has a hard time dealing with success and that everything she does and accomplishes is “ordinary.” When these feelings crop up, she says that “outside support has been critical. They won’t let me wallow in this place I get to sometimes.”

Being open about feeling inadequate, in addition to lending support when it looks like a peer needs it, are items any industry can certainly do better at—coffee included.

Do you feel you might be an impostor? Take this quiz!

* Name has been changed to protect the identity of the subject.

Jenn Chen (@TheJennChen) is a San Francisco–based coffee marketer, writer, and photographer. Read more Jenn Chen on Sprudge.