It was a sweltering hot and humid August morning somewhere south of Perugia in the Umbrian hills, and I was still one of only two people seeking shade in front of the tiny local train station.

The iconic Italian espresso bar and ticket booths that are always open were all closed during the almost three-week-long national holiday break. I had checked the bus schedules and knew beforehand that there would be limited public transportation during the journey, but the third and final transfer bus I had been waiting on for two hours after its expected arrival time left me uneasy as to whether I’d actually make it to the town of Montefalco that day to visit the Paolo Bea Winery.

This type of transportation waiting game is not unusual in Italy all year long, but take note that it’s particularly inconvenient in August. The seemingly obligatory “Ponte di Ferragosto,” (Ferragosto Bridge) observance used to be just a long weekend break, but nowadays most Italian businesses completely shut down operations after the first week of August until September to travel to the mountains and sea.

Italian vignaioli (winemakers), on the other hand, are facing one of the most delicate and unpredictable moments of their work year as they prepare for harvest, which was what I kept reminding myself when any thought entered my head to complain about my bumpy ride from Milan.

Vignaioli, in general, tend to have little time and patience for visitors during this period, so I felt especially grateful for the Bea family’s elevated hospitality from the moment I arrived. Paolo Bea’s family name has been in Montefalco, Umbria dating back to the 1500s, and over the past 30 years, it has become a household name for Italian wine lovers worldwide. Although the farm and winery bear his name, his two sons, Giuseppe and Giampiero have been managing all aspects of wine cultivation and production since the mid-1980s.

Paolo Bea worked his entire life on the farm with few problems, but a problem with making little earnings seemed to be perpetual. Recognizing the potential decline of the farm in an era of industrialized agriculture, Giampiero Bea took an ambitious leap in the midst of his developing career as a professional architect to help protect the family farm and the history of their land by joining his brother to reorganize the family business.

The primary business of the farm was raising cattle, but they had always produced and bottled small amounts of high-quality wine and olive oil in damigiane (demijohns) for personal consumption and to sell to the local community. When Giampiero Bea noticed the prospective economic advantage of producing and selling wine from a practically unknown and recently formed (1979) Italian DOC and DOCG zone, he utilized his expertise in navigating bureaucracy to start selling into the Italian market. Shortly thereafter, he started developing relationships with merchants that later imported his exciting terroir-focused wine initially into the United States and Japan.

Giampiero Bea also stands as the sole remaining co-founder of the Vini Veri consortium and wine fair, which he formed with the likes of Stanko Radikon, Angiolino Maule of La Biancara, and Fabrizio Niccolaini of Massa Vecchia to name a few. Now rolling into its 17th year, the wine fair’s humble beginnings are considered by some as the bedrock of the Italian natural wine renaissance.

Once I’d (finally) arrived, I was greeted within the white pebble driveway by Giampiero Bea and his youngest son, Pietro, who was hiding bashfully behind one of his father’s pant legs. As it was mid-afternoon, we all three sped off right away to visit his tree-trellised Trebbiano Spoletino vines.

As we drove on winding back roads through a nearby valley surrounded by sunflower fields, Bea would ever so often slow down and point out the window at random fields of sparsely-dispersed trees all completely enveloped in grapevines. Some were laid out in long roadside rows with vines extending from tree to tree like telephone wires, while some stood casually on their lonesome in the middle of a field. Having tried the elegant “Arboreus” wines made from these vines, it was a bit of a surprise to see them in such a wild condition.

Bea concluded the vineyard circuit with a visit to his coveted “Pagliaro” vineyard of Sagrantino di Montefalco on an enviable east-south-west exposure on a hilltop overlooking his winery and the city of Montefalco in the near distance. We spoke about the history of the region, the Sagrantino grape, and his constant battle with perinospera (downy mildew) while his son ran around through the vines.

After returning to the winery, Bea walked me through how they make one of my all-time favorite dessert wines, Sagrantino di Montefalco Passito DOCG.

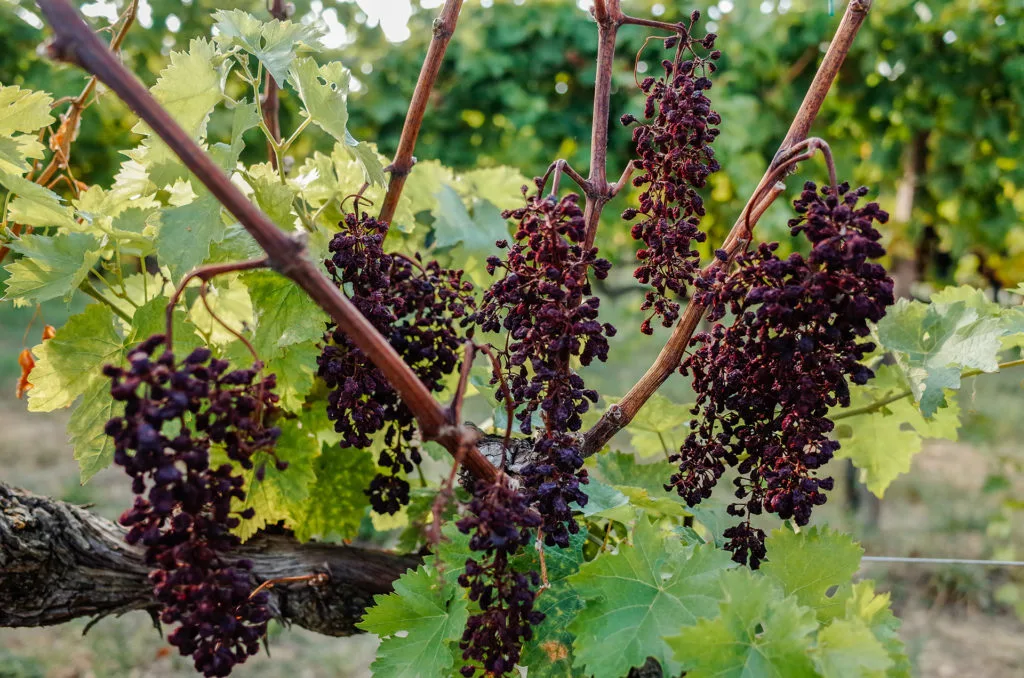

A late-harvested selection of Sagrantino grapes from the Pagliaro vineyard is dried to an almost raisin state for several months on woven cane racks before getting destemmed and crushed. The grapes only produce a tiny amount of concentrated sweet juice that then goes into fermentation for 36 days, then matures in the steel tank for 50 months, and is then aged in bottles for a full year before release.

They only make Sagrantino di Montefalco Passito when the harvest yield is plenty, so they only had one rack out for demonstration. 2017’s excessive rains, unfortunately, prevented them from producing the Passito for that year.

We shared a small glass from the 2009 vendemmia (harvest), and the payoff from Giampiero’s several years of work yielded an incredibly decadent and viscous mouthfeel with a savory and spicy sweetness like blackberries, persimmon jam, or a wine reduction sauce from a wild game roast, all without sending my palate to sleep for the day. If it wasn’t for its reasonably high price, I think it’s something I could drink regularly… and not just for dessert.

Satisfied enough by the lingering delight of sweet Sangrantino on my lips, we reserved the highly-anticipated cuvée tasting for after the interview and made our way to Giampiero Bea’s office and sat down to dig into some questions I’d been wanting to ask him for a long time.

Thank you for making the time to talk, Giampiero. Your design of this cellar is really extraordinary! Just the amount of consideration, in both function and aesthetic, suggests that your life as an architect left a lasting impression on your life as a winemaker.

Well, thank you. Yes, after my architectural degree in Rome, I worked for a company that specialized in building with organic and eco-friendly materials. Considering I continued to work as an architect while starting to make and export wine, you could say it definitely inspired the considerations I made in designing this newer cellar and office building in the sense of what materials we used in construction. We designed this building meticulously to take advantage of natural lighting and ventilation to optimize making consistently excellent wine, without ever having to waste energy to stabilize the temperature of our cellars. I had always had a concentration to protect the environment in my life… we grew up in an old way of life that agrees with the earth.

My work as an architect followed the same narrative that I live by as a winemaker. We are not here to create a dream business project and make an investment with expected returns. We are here to protect this terroir we grew up on; to protect our identity.

Speaking of identity, you were one of the first Italian winemakers to identify your wine and brand as vini naturali. How did you come to adopt the term and ethos?

I didn’t study winemaking and I most likely don’t have the same oenological background or experience as most of my contemporaries. My goal was simply this: to put our family wine from the table into a bottle.

My father always worked in a more-or-less natural way of agriculture, and so my brother and I just followed what we knew.

The importers we started to work with initially, like Neal Rosenthal from America for example, would return after a year of sales and inform me that their customers were fascinated by our respect for the natural way, and that I should continue on this path. Their feedback was essential.

Piano a piano [slowly but surely], they started to introduce me to other winemakers that were also on this path, like Stanko Radikon and Giuseppe Rinaldi and many more over time. This allowed us to exchange ideas, and to connect our small community of natural winemakers.

I could be wrong, but I’m not sure we were all calling it “natural” as an identity at the point, and especially not labelling the bottles in this way.

Do you mean that at that time, it was almost more of a risk than an advantage to market your wine as “natural?”

You couldn’t just go throwing that term around like it served as a label in those days. International consumers were seeking “terroir-driven” wines at that point, but the fascination with the term “natural wine” hadn’t arrived yet, and surely wasn’t accepted by wine critics and the conventional marketplace when it finally did come to fruition.

Because of all the bureaucracy we face as winemakers, if we labelled our bottles in the “wrong way” or as “vini naturali,” we could face repercussions. This is partially how I found my path to fight with the authorities in place, and to work through our Vini Veri Consortium to change the way we are required to label our bottles and treat our products.

At times, even the local government and denominations have found me to be a burden to their agenda. They tell us what’s best for us although it’s not true… and so we have to not just ask questions but take real action if it’s something we believe in.

Loopholes in natural wine marketing just temporarily fix one particular situation at a time per individual. Finding patience and taking the appropriate steps to work together against a systemic problem, piano a piano, can make a change that benefits all us vignaioli.

For example, we battled for a long time with competent Italian authorities to be able to manifest a more transparent bottle label: to label the exact amount of mg/l of total sulfites as well as the presence of added oenological substances, and even better for us: the lack of these substances. This was a goal of Vini Veri since the beginning.

After some time, we were presented with research from the World Health Organization and the UN that says the body weight of one person can determine what amount of sulfites their body can tolerate, and evidence of the possible adverse bodily reactions to these approved oenological substances. By our official request, the Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Food, and Forestry Policies has recently just moved to permit us to label what we had been dreaming of this whole time. Just using the words “natural wine” doesn’t mean or change anything.

You’ve seen all this evolve into a global culture that’s marketed by natural wine specialty shops, magazines, bars, and fairs including your own, “Vini Veri.” Any thoughts on all the changes?

It’s great of course, and we all benefit from the growth and consumer awareness. But with quick growth and popularity, also come many pretenders trying to jump on the trend and dilute the initial principles just for marketing reasons.

Like I was saying before, saying something is natural, whether a winemaker or a wine fair, doesn’t make it natural.

Many times, I meet winemakers that are far from being able to call their wines natural, and then I see them later featured in prominent “natural wine” fairs. One of the biggest natural wine fairs in Italy doesn’t even notice that many of their featured producers are using temperature control, adding excessive sulfites, and even filtering wines… Should it be allowed that a winemaker filter the soul from a wine and still call it natural?

Was that metaphorical or a religious reference?

You could see it either way. I am Catholic, but to me, God is nature; the first miracle. From the first piece of wood grows a leaf, a flower, a fruit and when you crush it…it becomes wine.

It’s not easy to see, but to us, there is an entire community of life on the skin of every grape.

Sometimes when there’s something I simply just can’t explain, although I do understand technology and science, I like to have a dialogue with the spirit to find the solution. I choose this path rather than trying to dominate every outcome.

As a winemaker, I’ve had many opportunities to get angry, curse a bad fortune, and try to control the outcome of my wine, but I instead followed the teachings of my faith to step back and observe to understand the small blessings in every minor tragedy. For example, In 2002, back when we were just making wine in the barn next to the house, 70% of our production was destroyed by excessive rains and plenty of vine disease, but the prior year our harvest was better than average I discovered that I, in fact, could use this opportunity to raise awareness directly with my clients about our choices to continue producing whatever wine we are capable of without the interference of tools and chemicals. Everyone really appreciated the value of our work in balance with nature, and it allowed us to create a unique label for that year, and raise the prices per bottle slightly to mitigate some losses.

Could you tell me more about the Trebbiano Spoletino vines that you grow in trees? Are there any advantages or disadvantages to raising vines this way?

Not many disadvantages except that it’s quite expensive to do, but yes we find it to work the vines’ advantage.

The soil composition of this valley didn’t permit phylloxera to attack the roots of the Trebbiano vines in the late 19th century, so most that still exist today are at least 120 years old, and we’ve found that some of the ones we replanted are over 150 years old. It is an incredible patrimony that is very important for us to maintain.

The Trebbiano Spoletino was always grown in the valley between Montefalco and Trevi, where we were earlier, but were predominantly cut down by the last generation to make way for corn, sunflowers, and grains. The last of these old vines could mostly be recuperated from the backyards of old homes that were only kept around to make family table wine.

We planted these ancient vines at the base of oak trees to grow in symbiosis with the tree. It’s an old way, but a very practical way.

This technique persuades the vine to grow with the tree and allows each vine to produce 50 to 60 kilos (110–132 lbs) of grapes each year. Harvest is laborious as you can imagine, but it’s really worth it.

We also have some Trebbiano on lower trellises for experiments, closer to the ground, it’s about 20% of our total Trebbiano, and I can say I notice a big difference in roundness and complexity in the glass.

Because the grapes grow so high off the ground, it also reduces the chances of disease and mildew.

As a producer of consistently excellent and drinkable Montefalco Sagrantino, why do you think that there’s always been a slight condescending tone from wine writers and sommeliers about the potential of the grape and its aggressive tannins and uncontrollable phenolic content?

The problem is not the grape, but the human who tries to fix it to taste like something specific. This is not my opinion and I didn’t conduct the research, but there were studies done at the University of Milan that the common Sagrantino vine has been heavily genetically modified. There have been 20 years of genetic modification, and now these clones are everywhere here, and the clone has since been registered as Sagrantino di Montefalco.

Apparently, the conventionally made Sagrantino has these characteristics that you described before because someone wanted to make them seem like a Barolo or Super Tuscan. There was also the desire to grow them closer to the river which is a much more humid environment.

It seems they want to fix the character of the grape, so through the cloning and modification, there become more problems to fix. There needs to be some modesty in this, but the problem is not small, because it compromises the value of this great vine, and it doesn’t deserve it.

I don’t want to sound presumptuous, although I do love to drink our wines, but people tell me they enjoy our wines for their bevebilita (drinkability), so you can draw your own conclusions.

We found our pre-phylloxera Sagrantino vines in the walls of an old monastery and is of the original lineage of the grape variety.

Oh wait is that the same Monastery that you’re working with to make orange wines?!

No no no, we sourced our old Montefalco Sagrantino vines from a monastery here in Montefalco; the Santuario di Santa Chiara della Croce.

What you’re thinking about is a Trappist Convent of Vittorchiano in Lazio. They cultivate their own organic grapes and vinify on location. They produce about 24 thousand bottles of wines a year labeled as Coenobium. I am merely a consultant and assistant on the project; the sisters do all the hard work.

You’ve been making sought-after and hard-to-find natural wines for 27 years now. What advice do you have, if any, for all the up and coming winemakers of today?

Obviously, I support anyone that decides to start on this path. They must have a true passion and will, but also the understanding if they have the capacity for this. This must be accompanied by the patience to listen to nature and observe its guidance. As the earth keeps changing, so must we adapt. I don’t know all there is to know, and if I stay like this, I will never stop learning and following a natural path.

Thank you again Giampiero.

Alexander Gable (@mrgable) is a freelance journalist based in Milan. Read more Alexander Gable for Sprudge Wine.