There is something undeniable happening when it comes to coffee and labor in the United States. But one size does not fit all. In the same year as a burgeoning worker uprising movement, a handful of coffee businesses around the country were exploring an alternative approach: converting to a worker-owned model. There’s a subtle but significant difference between a company having a union, and a company being worker-owned; both unions and cooperatives are examples of collectivity, where you are stronger as a group than as an individual, but the practical reality of these modes of operation look totally distinct.

You can certainly open a business as a cooperative, like many do, but another option is to convert an existing one to a cooperative model. The process sounds a little daunting so I talked to three coffee cooperatives who recently and successfully converted. They gave me a behind-the-scenes look at their conversion processes and also shared some insightful tips for those who want to explore this.

No conversion is quite the same as another but there were a few similar trends between their stories. The owners in each case were favorable to the idea of conversion and contributed financially to it. There was also an existing culture of employees invested in the company’s future and company values that aligned with being worker owned.

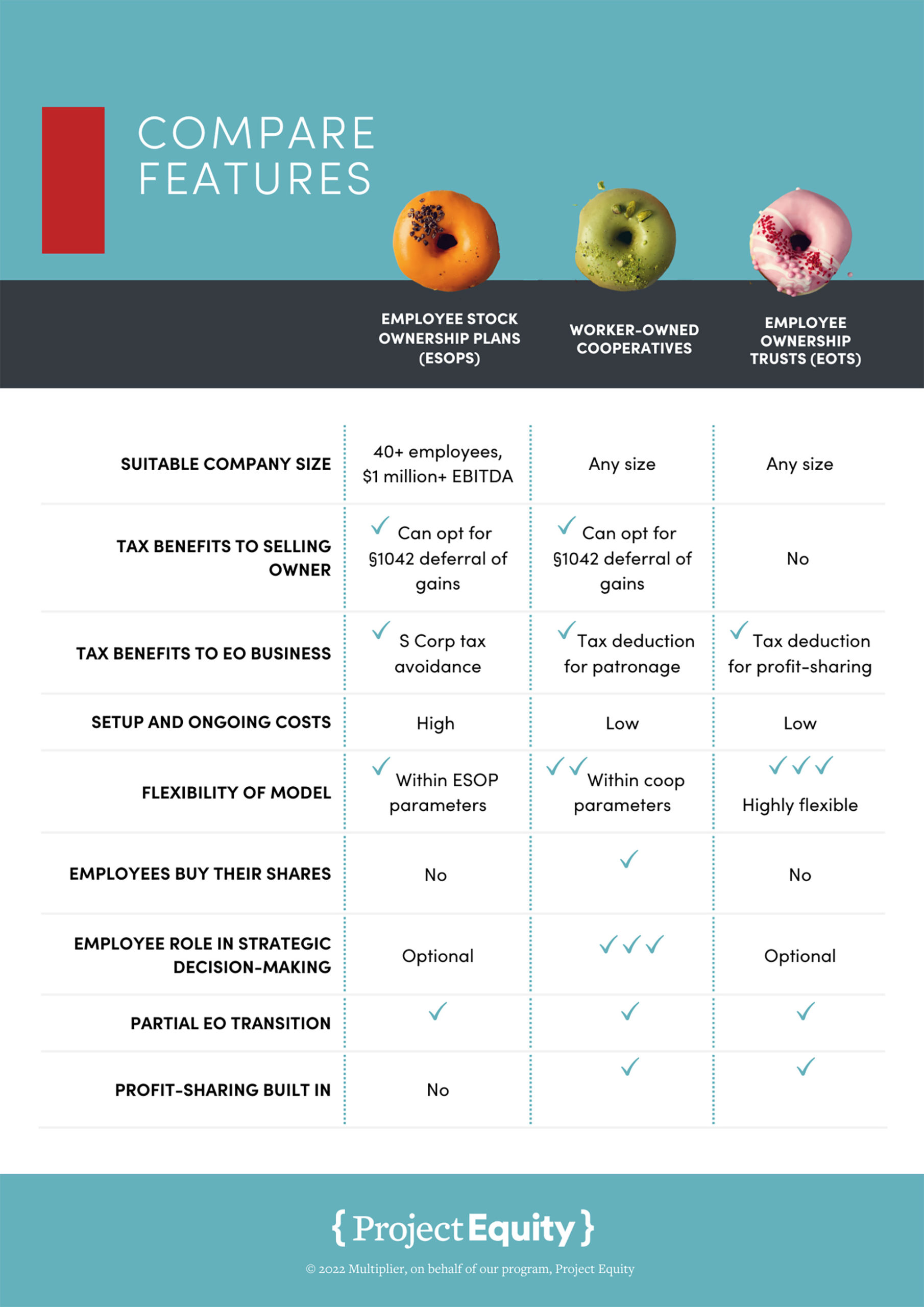

There are three different forms of work ownerships out there: employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), employee ownership trusts (ESOTs), and worker-owned cooperatives. Here, we focus on worker-owned cooperatives, the only type where employees buy their shares and are assured to be part of the decision-making process.

Afterglow Coffee Cooperative

In Fall 2021, Afterglow Coffee Cooperative in Richmond, Virginia announced its presence to the world. Fans of Lamplighter Coffee recognized the Summit Avenue address as Lamplighter’s former roastery-cafe location. When the pandemic hit, all three Lamplighter cafes closed, and the roastery became wholesale only.

By that point, worker-owner Alan Smith had worked as a barista for two decades and been with Lamplighter since 2010. With worker ownership already a discussion topic, Smith and his colleagues saw all the “horrible stuff happening in our industry” and the pandemic as a catalyst for necessary change. “How can we use this as an opportunity to create the change we would like to see?” he remembers their feelings at the time. “Might as well go all the way and try to have us all own the business.”

Lamplighter’s owners were receptive to the idea and together, they negotiated the cost of purchasing the location that included both the roastery, its wholesale business, and a retail bar. “There was no animosity, there was no struggle to get them to understand the ideals behind why worker ownership would be a good thing for them and for us,” says Smith. “We were in a very ideologically privileged place.” The buyout would give Lamplighter’s owners some cash to keep the original cafe on Addison Street upright through COVID. The entire process took about six to eight months and was relatively smooth.

Just over a year into becoming a cooperative, Smith names communication, being under-resourced, and creating governance from scratch as some of the biggest challenges to overcome. “It just feels in order to do it really well, we need a lot of resources that we just don’t have access to as a small business,” says Smith. But that doesn’t change his positive outlook of being able to create their own priorities. “Even if we can’t meet all of them all the time, we still don’t have to take no for an answer from somebody else who isn’t us.”

Afterglow now has six worker-owners. If you can’t afford the minimum buy-in, then you can work at a slightly reduced rate for six months to earn the buy-in equivalent. As a worker-owner, you have one vote (all important decisions require consensus) and an equal share of the business as the others.

Smith shares some parting advice for workers exploring collective action: “You have a lot more power than you realize. One of you is replaceable, all of you are not. I feel like a lot of people are just so beaten down by service work that they really don’t believe that change is possible.”

Morning Bell Coffee Roasters

Even before the conversion, Morning Bell Coffee Roasters’ employees have always been democratic in nature. Decisions like scheduling and green coffee buying were made by group consensus. “Our shop culture has always been one where management has full trust in our employees, and I’ve found that to be more unique than I could have imagined,” says Nadav Mer, the founder and former owner of Ames, Iowa-based Morning Bell. For example, every employee had a key to the shop and veto power over hiring decisions.

Worker-owner Kari Storjohann was an employee at the time and, after seeing Spyhouse’s unionization efforts, had brought up unionizing to Mer. “He said, ‘I’ll do you one better. What if we have a workers’ cooperative?’” she recalls. Another worker-owner, Maxwell Westlake, remembers it being a cool idea to become a business owner, albeit a little frightening. Iowa had no worker-owned cooperatives in the state, so Morning Bell had to cross state lines to obtain legal help and formation guidance. The ICA Group, the oldest national organization dedicated to the development of worker cooperatives, sent someone out to walk them through the process and explain both challenges and benefits. Westlake says, “They helped with a lot of the early stages and explaining the concept to us.”

The original plan was to have Mer stay involved as a worker-owner, but once he decided to move for his wife’s new Texas A&M job (Mer also now works there), the plan pivoted to selling the business to its current employees.

After exploring all the financing options out there, Mer decided to personally finance the transition and provide a loan for the cooperative to purchase the business. “It took some work getting my mind around the idea that the equity in the business isn’t being sold to anyone, there is no ‘new owner.’” he says, describing the equity as more like “community property.”

Morning Bell recently passed its one-year cooperative anniversary and now has five worker-owners and two additional employees. At the one-year employment mark, there’s the option to join as a worker-owner at a buy-in of $1000, an attainable amount but still high enough to show a level of commitment.

“As a job, I can confidently say it’s, by far, the best job I’ve ever had. And I’m guessing the best I ever will,” enthuses Westlake. “We’ve been able to do some really good things—both for employees who are owners and employees who are not—and within the community that I don’t think we would’ve been able to do otherwise.”

Gimme! Coffee

Of the three cooperatives featured here, New York-based Gimme! Coffee is the youngest at six months old. However, it’s also the largest (at the time, it had 53 employees and converted about 75% to worker-owners). The overall process took two-and-a-half years to complete, far beyond the initial estimate of one year.

In 2019, Gimme’s original owner Kevin Cuddeback privately expressed his desire to retire and move out of state. Colleen Anunu, now Gimme’s Co-Managing Director and Head of Product Development, was brought on as interim CEO with the intention of helping with the conversion process. Anunu had previously spent a decade at the company before leaving in 2013. When Anunu returned, they described the company culture as “deferred maintenance,” where “you could just tell that no one was really trying to create collective empowerment between all of these different, separate silos of the business.”

One of the first phases of conversion is conducting a feasibility study to ensure that the business is able and ready for the structure change. This includes analyzing finances and gauging employee interest. Overall, it took at least six months, with the first portion being completed quietly without employee knowledge in case the financial analysis wasn’t positive.

After the employees agreed to pursue the co-op model, a transition team was created to prepare the co-op’s foundation and oversee the sale of the business. Running concurrently with this was the Gimme Barista Union’s decertification vote. To some, the conversion timing was suspicious and felt like union busting; it also led to the withdrawal of Project Equity, a not-for-profit organization that specializes in conversions. “I was the only barista who was a part of the transition team, and people didn’t necessarily want to reach out to management cause of trust issues,” says Wendy Roth, a lead barista and board member.

Once meetings began and financial information was shared, the tone changed. Production assistant and board member Quinn Knight says, “Everyone’s participating, everyone’s energized, everyone is wanting this to happen because we all have common values and goals, and we’re bringing this to the table.” Roth and Knight both swear by the created bylaws and their decision matrix, advising others to get these cemented as early as possible. Referring to union-busting suspicions, Roth also advises “being as transparent as possible with everything that you’re doing is super important.”

Benefits

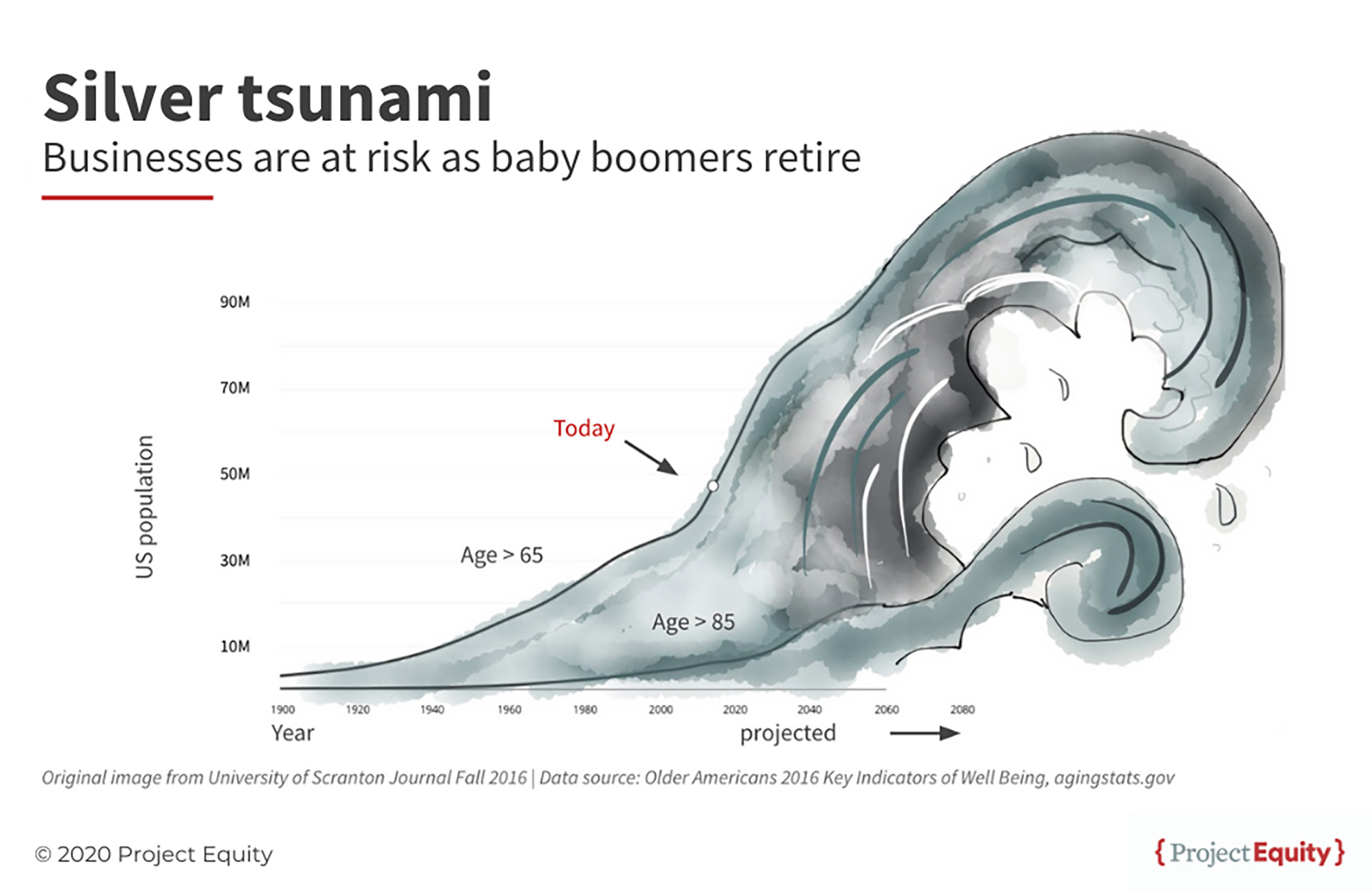

Co-ops solve a few big issues that are plaguing small business owners today, including one nicknamed the “Silver Tsunami,” for the fact that half of all privately held businesses with employees have owners over age 55. In addition, one out of three business owners over age 50 has a hard time finding a buyer, leading to business closures or sales. Keeping a local business alive also means that it can circulate three times more money within the community than an absentee-owned corporation.

Whether you’re the owner or the employee who has an interest in forming a cooperative, a conversion begins the same way: with research. Talk to other cooperatives and reach out to organizations that are established to help cooperatives. “One of the founding principles of all cooperatives is cooperatives helping cooperatives,” says Anunu.

Mer says, “In my opinion, the workers cooperative structure might be the most optimistic way for us to build equitable systems that work well at small scale within our larger capitalist economic system.” Research from the National Center for Employee Ownership supports his opinion. Compared to workers who aren’t owners, employee-owners have 92% higher median household wealth, 33% higher income from wages, and 53% longer median job tenure. Cooperative-run businesses also boast a higher productivity rate and lower turnover. And finally, as told to me in my history of coffee unions article, they also offer a solution to increase wealth equity among the immigrant population.

Financial challenges

As one can imagine, financing is one of the biggest hurdles to overcome in a conversion. Accountant and legal fees for the smaller businesses were in the thousands while Gimme’s was around $15-20k.

In addition to professional fees and the costs of purchasing a business, there could also be conversion consultant fees ($50k for Gimme). Afterglow purchased the business but it was “able to do some of the purchase in trade for coffee. So we gave them credit on their account, basically I think $20,000 in product,” says Smith. For Gimme, lender Shared Capital Cooperative funded 70% of the sale and Cuddeback self-financed the remaining 30%.

In response to increased interest in conversions, more monetary resources are available. Funds like Co-op Cincy’s Business Legacy Fund and the Cooperative Fund of the Northeast exist to provide loans for this process. “Each cooperative lender that we pitched to included long periods of discussion and clarification about our proposed cooperative structure, business plan, and membership engagement,” Anunu tells me. Gimme ended up going with a different lender after the first one offered unrealistic terms that would’ve had members putting up $6,000 each (the current buy-in is set at $1,300, which can be paid off over time).

A bright future

At the end of each interview, I asked everyone the same question: Would you do it again? We’d gone over the challenges already, and I wanted to know if what seemed to be a difficult process was worth the result. The answer was a resounding YES with enthusiastic praise for the co-op model. Everyone who talked to me had excitement in their voice and encouraged others to explore the option.

People felt more empowered in their jobs, were learning more about business operations than ever before, and held a generally more positive outlook on their future. Both Morning Bell and Afterglow have already sparked conversion interest in nearby businesses, with Afterglow going as far as trying to hold educational workshops.

“The culture is very different now. People are much more excited about the future.” says Roth. “It’s a great business model—for people that don’t necessarily have college degrees and have ambitions to be business owners—to get that experience still. I think it’s pretty incredible.”

Knight agrees, explaining that she’s had to support herself since age 16 and that she doesn’t hold a college degree. Building a house seemed like a pipe dream until now. She says, “I feel like I’m actually gonna be able to do a lot of things that I’ve been dreaming of doing with my life.”

Jenn Chen (@thejennchen) is an Editor At Large at Sprudge Media Network. Read more Jenn Chen on Sprudge.