In many ways The Way Back to Yarasquin is a story about origin – it’s about origin of coffee, it’s about origin of people, it’s about origin of desire or drive, it’s about the origin of a business, and it’s about going back to origins.

The Way Back to Yarasquin, a documentary by Sarah Gerber, has been screening around the country recently, and I caught it at The New Parkway, in Oakland’s Uptown neighborhood on September 25. The film tells the story of Mayra Orellana Powell, a native of both Alameda and Honduras who owns and runs both Catracha Coffee Company of Alameda, CA, and a small coffee farm in her home town of Santa Elena, Honduras.

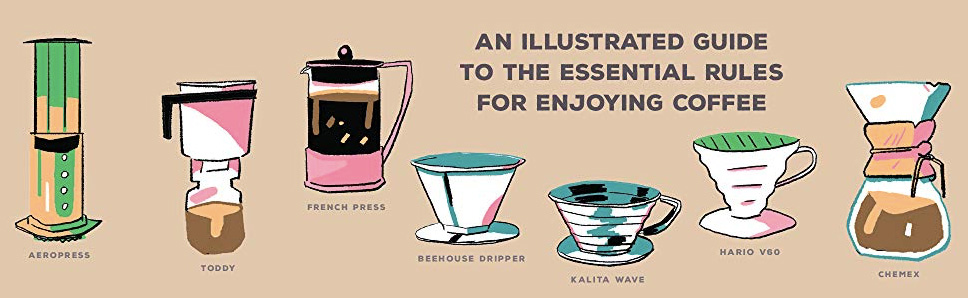

The film opens with some shots of processing coffee, and quickly progresses to portrait of a town, Santa Elena, in Honduras, and the farmers that live and work there. The story is framed by the economic conditions: many of the farmers take out loans to support their farms in the off-season; these loans come at absurd interest rates and stipulate that the farmers sell their coffee to specific commodity buyers. This cycle of debt appears to be nearly inescapable to the subsistence farmers of Santa Elena.

That’s where Catracha Coffee and Mayra Orellana-Powell come in. Unlike many coffee origin stories, one of the really exceptionally interesting parts of Catracha Coffee, is that Mayra Orellana Powell is from Santa Elena, and owns a small farm there. She also acts as an importer, a salesperson, and co-op organizer. Mayra Orellana-Powell came to the United States to study business, returned to Honduras where she met her husband Lowell Powell, and then the couple returned to the United States. Eventually, Catracha Coffee was started as a way to both get back to Yarasquin, and a way to give back to the farmers there.

Catracha Coffee advocates for the coffee of Santa Elena and helps improve the quality of that coffee through education and re-investment. Catracha Coffee gives back profits to the farmers, and after the film, Orellana-Powell said that the farmers used these payouts for everything from new washing stations and drying patios, to dental care, and better education for their kids.

The movie, which runs about 35 minutes, refreshingly doesn’t portray Orellana-Powell, or anyone else as any kind of savior – it’s insistent on portraying the intertwined nature of labor, commerce, and culture. Catracha Coffee is a part of the community of both Santa Elena and the Bay Area; that community includes everyone from the pickers, to the farmers, to the importers, roasters, baristas, and ultimately, the customers.

Orellana-Powell traces the motivation for starting Catracha Coffee to her grandmother, who she wanted to make proud. Her motivations are about community, and family, but if there is a message to the film, it’s about the community of trade. Max Fulmer of Royal Coffee said during the Q&A, “More companies need to be investing in coffee farmers but not using the farmer as a marketing tool.” The story of Catracha Coffee might not propose a different trade model, but it may suggest the possibility of a style of trade where everyone involved is respected and given the resources to both survive and reinvest in improvements.

The Way Back to Yarasquin is certainly worth watching if you’re interested in where your coffee comes from, or if you’re just interested in a good story. It’s also a great place to start a conversation about what trade in the coffee industry can, and possibly should, look like.

Leif Haven (@LeifHaven) is a writer living in Oakland. His work most often appears in SF Weekly and HTMLGIANT. Read more Leif Haven on Sprudge.