“Is there anything in particular you’re looking for?”

“Well…Chardonnay.”

A dead pause. We’re in the hippest natural wine basement in London, and I’m looking for buying recommendations. I might as well be asking for VHS reruns of Lawrence Welk.

“I’ve got some lovely De Moor Aligote here, it sells quite quickly. Does it…have to be Chardonnay?”

“I’m afraid so, yes.”

And in that moment, there down below Hackney Road, I feel the shiver start across the back of my neck. It runs from your ears up underneath your eyes, down to the corner of your lips, a trembling little mini-seizure, accompanied by the start of moisture in the nasolacrimal ducts, but it can be opposed. I can fight back against it, and I must, because if I start crying here, in this basement, 5,000 miles from home, in front of God and England and the caviste, in that order, well, it’s all too ghastly for words.

“I know it’s…lame but I’m…working on a project. Normally I’d be asking for something else but right now it’s Chardonnay, please.”

The wine guy pulls a couple of bottles—lovely white Burgundy—then settles me up, and I leave quickly, bottles in arm, up the stairway and out onto the greyscale street. It’s one of these horrible British bathtub days, cloudy and claustrophobic and humid, and I go stumbling down the street aways in a haze. When I’m safely far enough away from the bar I set the bottles on the sidewalk and let the tears come properly.

In the fall of 2017 my father was diagnosed with cancer. As an attorney with his own private practice he was, for more than four decades, an upstanding member of the Washington State legal community. William R. Michelman Esq.—judge and scholar, at once feared and grudgingly respected by his opponents and adored by clients of all means and backgrounds. There’s a temptation to lionize our elders in these situations but with Dad it hardly feels like a stretch: he was the attorney you dreamed of representing you when shit went wrong, and the guy you’d least want to oppose in court.

In the case of my father, what was discovered was a particularly aggressive and pugnacious form of cancer, in the advanced stages of growth. It was precisely the effect of an emotional car crash for my family—the five of us then, my parents, me, and my two brothers. But in the wake of Dad’s diagnosis, my siblings were uniquely positioned to help. Aaron—my big brother, based in Atlanta—just so happened to practice roughly the same field and style of law as Dad: personal injury and criminal defense. He rushed in to help any way he could, eventually gaining emergency admittance into the Washington State Bar Association to help move a critical case towards settlement. Adam—my middle brother, based in Chicago—works in the field of insurance and medical legal compliance, and has first-hand experience managing end of life eldercare needs on behalf of our grandfather, who passed a few short years ago in Florida. Adam could talk Mom through options based on insurance and Medicare. Or maybe it was Medicaid—I’m still not sure what the difference is.

I had no such expertise to offer. If you need a restaurant recommendation, or a list of good coffee bars within driving distance of our family home in the suburbs of Tacoma, or a multi-thousand word essay on the existential ennui of this experience, I’ve got you covered. In terms of actual practical help? I felt deeply, utterly useless.

But I could pour wine.

Chardonnay, to be specific, which is my mother’s favorite wine. There has been a bottle of Kendall Jackson, or Chateau Ste. Michelle, or maybe Sutter Home Chardonnay in our refrigerator for as long as I can remember. My mom—who is gregarious and social, given to close lifelong friendships, and has since the 1970s been told she looks like Diane Keaton—is the sort of person for whom all white wines are Chardonnay, a lesson I learned a few years ago, in happier times, at a New Year’s Eve party to which much of the suburban neighborhood was invited. I’d brought along a gorgeous bottle (a magnum actually) of “Magic of Juju” by Domaine Mosse, really stunning Chenin & Melon de Bourgogne from the Loire. It was quite popular at the party, and my mom recommended it with aplomb to her friends: “You’ve got to try this Chardonnay!”

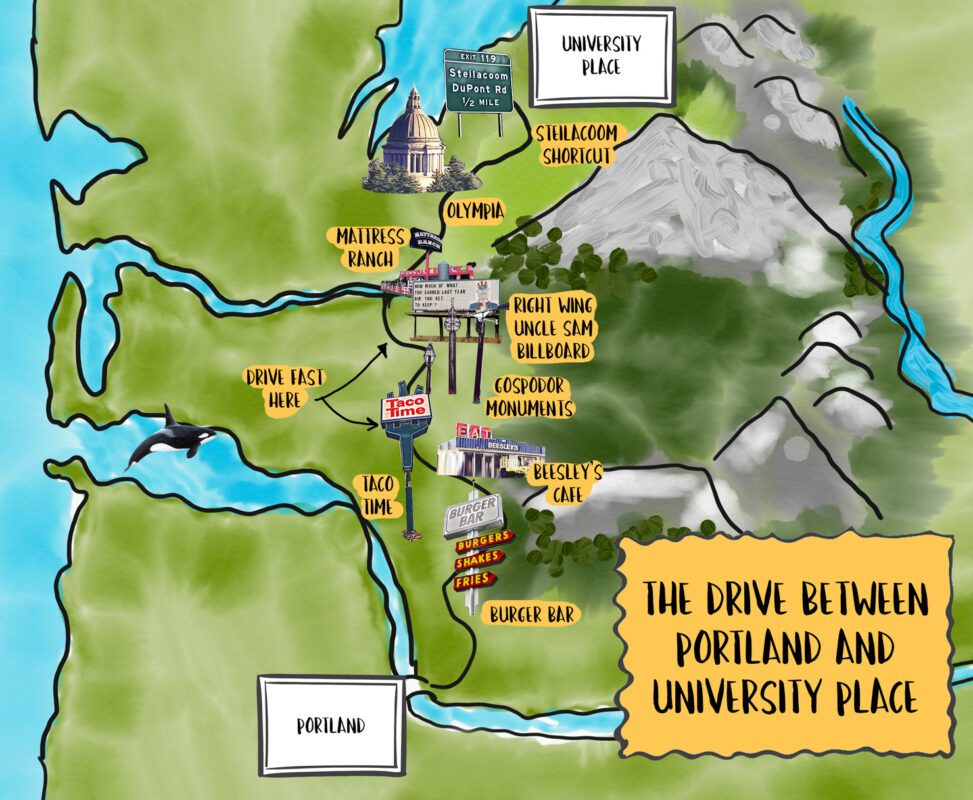

When Dad was diagnosed the more important thing I could do was be there. My brothers required air travel to visit; I was a two-hour car ride away—more like 90 minutes if you did the drive at night and really gunned it between Kelso and Chehalis.

And so I started coming. Sometimes for just a night, sometimes for a few days, or a whole week. There were many nights he spent in the hospital; my brothers and I did our very best to try to make sure Mom would spend as few of those nights as possible alone at home. And I never came up to Tacoma empty-handed. If I couldn’t help work out the legal knot of winding down Dad’s private practice, and if I couldn’t advise Mom on how to navigate the endless bullshit of insurance compliance and claim maintenance, then I could damn well make sure she was drinking good Chardonnay. I took it as my task, a glorious distraction from the cosmic pain and tragedy unloading itself upon my family. It become my treasure hunt as I still grudgingly traveled for work over these months—my monkey’s paw, my purpose, the one thing I could control in a situation for which control was non-negotiable.

Is there any other grape with quite the same cool/uncool duality as Chardonnay? How is it that the grape synonymous with suburban moms is also made into some of the world’s most sophisticated, sought-after, and expensive wines? It is capable of such verve and beauty, such dextrous complexity. It ages gracefully. It is a universe of styles and expressions. It contains multitudes. And yet… and yet it is the eyeroll grape, the split that launched a thousand snarks, typically prefaced by adjectives like “buttery” or “dry.” I know natural wine shops that keep “sucker bottles” specifically for this kind of Chardonnay drinker: boring, expensive, bland.

At the time—the start of it all—I had an ambivalent relationship towards Chardonnay. White Burgundy was interesting, of course, or at least what I could afford of it; and I’d been exposed to a few intriguing expressions of Chardonnay from places like South Australia and the Willamette Valley. But my own path as a wine drinker—and eventually, a wine writer—had hewn more towards the wild stuff. Natural wines that took chances and blew minds and tasted nothing—and I mean nothing—like those swigs of Sonoma-Cutrer I snuck from the fridge back in high school.

But circumstances have a weird, cruel way of amending a narrative. One of my dad’s favorite songwriters once wrote, “Time runs like a fuse,” and in my whiplash following the diagnosis, I found myself reaching out for something, anything, to give some normalcy to my now disordered life. Chardonnay was it—it became a schtick with the shopkeeps and cavistes—”I’m looking for a Chardonnay,” I’d tell them, growing bolder as I went along, not always reduced to tears like that little incident in London. It became a project, under construction and never finished, and a kind of shibboleth for my mother and I to share together, as late summer turned to fall, then winter, and then finally, paradoxically, to the coming of death, in spring.

Sometimes it’s the little bits of math that creep up in your head, cold hard numbers that calmly strip bare the cruelty and unfairness of any particular situation. We took L after L on this cancer thing; Dad lived barely nine months after his diagnosis, as waking nightmare of lengthy hospital stays, emergency surgeries, chemotherapy—good-for-fucking-nothing, life-sapping, soul-sucking chemo—then alternative therapies, experimental treatments, second opinions, palliative care, and finally, a few final weeks of merciful hospice. In November they gave us four to six weeks, but Dad lived until May.

Grief comes at you in weird, unexpected ways, and in quiet moments you can’t predict or prepare for. You might be driving around, listening to music, and a song comes on you dig—say “Hold Me,” the Fleetwood Mac hit from Mirage, their underrated 1982 record. And you start tapping your foot, and you sing along a little bit with the lyrics, and you start thinking, “Gosh, I wonder how old these guys are?” Because Dad was 70 when he died. Didn’t make it to 71. So then you pull your car off the side of the road, because you’re curious, right, and so you look it up on your phone, and it turns out Mick Fleetwood is 70. Both Dad and Mick were born in 1947, which seems like an eternity ago when you write it out, but is actually exactly 70 years ago. And you get to thinking, right, here’s Mick Fleetwood—great drummer, consummate rock personality, big fan of his band, etc—but he famously treated his body like a flaming garbage bin for much of the 20th century. He is an all-time rock and roll drunk and notorious cocaine abuser! It takes but one Google—for “Mick Fleetwood Cocaine”—to reveal that the Mickster is estimated to have snorted $60 million worth of white powder in his life. And he is, by all accounts, still alive and doing great—indeed, on tour this summer, with tickets starting at $125 for the nosebleeds (pun intended).

Dad, by contrast, only ever drank on vacation, once or twice a year, which was great fun for us all once his kids were old enough to join in. A vodka soda maybe at the end of the night in Disney World, or a beer on the cabin patio in Montana. That’s it. He lifted weights; he exercised most every day. He helped coach his kids’ Little League teams. He didn’t eat mayonnaise, or salad dressing, or real butter. Maybe he smoked a little pot back in the 70s—who knows. There will always be things about our parents we don’t know. But he was no Mick fucking Fleetwood, that’s for sure.

Dad drops dead at 70. Mick Fleetwood drums on. And you’re pulled over on the side of the road, crying now, helpless, and the radio has long since moved on to another song, and grief, like a cut that won’t clot, bleeds out down the side of your face.

I kept most of this stuff to myself, quiet and internal, and for what it’s worth I’m terrified, you know, about writing this at all, and the thought of publishing it, because it’s just so shudderingly public, and in this day and age of overexposure and lives writ large on the digital stage and social media addiction and status seeking shrunk down to the size of an iPhone, shouldn’t some things stay private? Must every last fucking thing we do, every tragedy and achievement, be economized?

I keep the tragedy to myself but in the fall I start a hashtag—#chardonnayinthesuburbs—to chronicle the bottles I’m sharing with Mom in Tacoma. The first entry is from September 2, 2017, and it’s a bottle of Clos Beru Chablis Monopole, imported by one of America’s really great natural wine seekers, Zev Rovine. A week later I came back with a bottle of Rene & Vincent Dauvissat’s Chablis Premier Cru “La Forest,” followed in short order by a stunning bottle from Jean-Francois Ganevat’s linear, mineral “Cuvee aFlorine.”

It’s all chronicled on Instagram, and there between the lines is the real story, unfolding across each bottle. Our early hopes for recovery were pinned on a surgery to remove Dad’s tumor; the standard of practice calls for chemo first, then an attempt at surgery. The human toll of chemotherapy is well-documented and I won’t pretend at an ability to add anything to its volumes, other than to say it was devastating for my father and for everyone who loved him to watch him go through those weeks and months. I’m not going to bog down on this part because as much as any of this is supposed to be exegesis, writing as therapy, it’s too fucking painful and clinical to really spell it out just yet. Basically, the chemo doesn’t work, and the surgery gets botched, and it starts to look like we might be looking at a seriously accelerated endgame. The surgeon quotes us four to six weeks. It’s late November.

As the situation turns dire, the wines become more fine and precise: I treat my mother and myself and anyone else within drinking distance to a dazzling battery of Chardonnays from around the world, sourced from my various trips over the year, or shipped in, or hunted out in across the Portland urban area. Division Winemaking Co.’s Chardonnay “Un” from the Willamette Valley; Gentle Folk’s Chardonnay blend “Scary White” from the Adelaide Hills; Massican “Hyde Vineyards” Chardonnay from Napa; Jo Brix “Limestone & Schist” Chardonnay from the Rorick Heritage Vineyards in Carneros; jaw-dropping, finely pointed, endlessly morish Moreau-Naudet Chablis Premier Cru “Forets”; Philippe Pacalet Chassagne-Montrachet. A Thanksgiving dinner of take and bake pizza and Tissot “BBF” Cremant du Jura Blanc de Blanc, with Dad in the emergency room.

And then the weirdest thing happens. Cancer’s agony is so achingly specific, in that it affords those orbiting around it time. Slow motion, fast forward, pause: cancer is the controller. Our surgeon turns out to be wrong. We don’t get four to six more weeks, we get four to six more months. Dad comes home from the botched surgery to something resembling normalcy, or at least a new normal, and Mom goes about her new life too, caring for him and helping him wind down the final motions of his law practice. My parents were married for 45 years. It is an incredible example of devotion and love for my brothers and I, that we can only hope to learn from. Dad comes home, and the panic is downgraded, replaced by the slightest glimmer of hope. One of the experimental therapies might take. He may qualify for a study. We have time—nobody knows how much, but we have it.

And so I keep coming, but for visits with Dad that don’t require endless trips to St. Joseph’s Medical Center, dropping off the car at the valet, checking in at the front desk, placing my hands beneath the sanitary dispenser, hearing its dispassionate mechanical whurr-ZIP! as it spits out a pre-portioned spurt of antibacterial liquid, walking down the long hallway through the double doors and up to the bank of elevators, riding those elevators surrounded by nurses on cell phones and patients in wheelchairs and families with the same emotional-whiplash look on their faces as I have, and then off the elevator on the cancer floor ward, through another set of double doors, checked in at the front desk, off with your coat, on with a plastic gown and a face mask, and another dose of medical grade Purell from the dispenser, whurr-ZIP!, and then at last into Dad’s room, where the fight was on. How I hated those rooms. But we got past it for a while. We got a few more good months with Dad, at home, for which I feel so grateful and lucky, like an earthly eye of mercy inside a hurricane.

I tried really hard to make the most of it, to be there for Mom in those months and be present with Dad. In early February we ate dinner at home, in my parent’s dining room, and Dad joined us. I brought along a bottle of Domaine Roulot Auxey-Duresses 2015. I knew full well we’d be murdering this wine young; white Burgundy like this, you want to give it a decade at least, under the best circumstances. But these were not the best circumstances, and I was out of fucks to give. We opened it then and there. It was reductive and young, but oh so tasty, with linear layers of acidity and roundness in concert, like a beautifully constructed cocktail or the juice of some sublime unnameable fruit. Dad joined in for a glass—they’d asked the doctor if wine was okay with his medication regimen, and been given express permission not only to drink a glass, but to enjoy it. And we did.

I poured him two, in fact.

The lights start flickering, and I keep coming with more Chardonnay, pouring liberally, as though its reflective, optic qualities alone could fight back the darkness. Olivier & Alice De Moor’s “Coteau de Rosette” Chablis; Champagne Jacques Lassaigne “Le Cotet” Blanc de Blanc (Dad had a glass of this as well, and loved it); La Monacesca “Ecclesia” IGT Chardonnay from Marche; Fred Cossard’s Domaine de Chassorney “Bigotes” from Saint-Roman; JJ Morel’s entry-level living Bourgogne from Saint-Aubin; Johan Vineyards unfiltered sur lie “Visdom” Chardonnay from the Willamette Valley; more Freddy Cossard, this time his negociant Jura Chardonnay from Ganevat’s vineyards near Rotalier. We drank this last one, Mom and I, at a little hibachi restaurant deep in the suburbs, where she is something of a regular, and thus charged no corkage fee. It was after a long day together with Dad at the hospice facility, during which time I experienced the finely pointed pathos of interviewing my own father for his obituary, noting his favorite record (Sgt. Pepper), book (Gone With The Wind), and films (“Casablanca”, “Saturday Night Fever,” and “Apocalypse Now”) for posterity. Then we watched the game together, as the Seattle Mariners dropped an otherwise meaningless April contest to the Oakland Athletics, same as it ever was.

On Tuesday, the first of May, I saw with my father in the hospice facility alone for the last time. He was in something like a pre-death coma; I’m not sure what the right term is for it. He couldn’t talk, or open his eyes, but his expression changed with stimulus, and so I sat there talking to him until I could think of nothing more to say, and then we listened to records on his iPod. It was all the same stuff I grew up listening to with him in the car, running happy Saturday morning errands here and there across the suburbs. The Cars. The Beatles. Simon & Garfunkel. We listened to Jackson Browne’s “Lawyers In Love” and laughed. We listened to Jackson Browne’s “The Pretender” and cried. We sat together, and I worked on what I wanted to say for his obituary, thumbing notes into my phone, knowing full well that my father, himself an All-World workaholic and task completer, would appreciate my own industriousness, even here, with death all around us, as “The Fuse” comes on the stereo again.

When my father died we drank Chablis. Cold, cool, clean, hydrating Chablis from Domaine Fevre, procured from a sympathetic wine shop in Portland and ordered via email, with the subject heading “Chardonnay Emergency.” His death was a relief and a mercy, an end to suffering, and also the beginning of a new and previously unimaginable gap in my life that will never be filled in. You cannot actually fully recover from the pain of losing a family member; you just get a little more numb to it, day by day, week by week. It is exactly the feeling of an emotional concussion. You can rebound, eventually, but you’re never quite the same.

I’m proud to say that we threw Dad a really epic memorial service, complete with black and white cookies, a rabbi, and an overflowing platter of bagel and lox. I poured wine there, too; emptied out the cellar, in fact, in full on “fuck it” mode, pouring tiny production ungettable bottles by Christian Ducroux, Ruth Lewandowski, Francois Dhumes, Anders Frederik Steen, and many more. I didn’t think to photograph it all. I just opened and poured, then opened and poured again, in a furtive attempt to transubstantiate my grief into wine. It gave me something to do, gave me a task to focus on, which carried through to that night’s memorial dinner, during which I poured a truly glorious magnum of winemaker Chad Stock’s “Dijon Free” Chardonnay from the Johan Vineyards in the Willamette Valley. I procured the great bottle from its maker directly upon release, a few years ago, with the full intention to keep it in my cellar for the next decade or longer. But my father’s death blew that up, recalculated that equation, and I stopped caring about cellaring anything, or holding back on what would or would not be opened.

And I think that’s probably okay. On the one hand, excess for the sake of it is dangerous, even as a well-deployed coping mechanism. But on the other hand, there are these rules in wine that get passed down, unquestioned, accepted as gospel and challenged only by heretics. One of those is the rule that says you’re supposed to sit on the really good stuff until it’s ready. But what about when I’m ready? What about when my entire fucking family is grieving, and my dad is dead at 70, and Mick Fleetwood is out on tour, and we’re standing together for the Mourner’s Kaddish? What about then?

I say drink the good wine now. Don’t wait. Drink it cool and easy with the people you love, or when the situation is heretofore unimaginably sad and painful and only the briefest distraction afforded by pleasure can salve the wound. Pour everyone else a glass first, then pour a nice big one for yourself. You don’t know how much time you have.

I will say that over these last nine months I’ve really come around on this Chardonnay stuff; I expect the grape’s vast capacity for complexity to be a new running narrative in my life, as I continue shopping near and far for bottles to squirrel away for the next visit home. Dad made us all promise that we’d take care of Mom once he’d gone. Some promises are challenges, but this one feels obvious and easy.

And in the process my mother—whom, it should be said, has a great many years ahead of her as a grandmother and friend and living breathing human on Planet Earth—has become something of a glorious wine snob. She knows her Chablis from her Maconnaise, and which she prefers best. (It’s Chablis.) She and I agree that we both need to drink more Freddy Cossard and Jo Brix; we disagree, however, as to the sherried pleasures of oxidative Jura Chardonnay sous voile, or that the acidity in late-harvest Chardonnay dessert wine is one of drinking’s purest pleasures (in my ardent view), or that certain wines are amplified with the addition of ice cubes (in her versed opinion).

Mom can look forward to many more years of us sitting together at our family home in the suburbs, listening to old music and watching the Mariners lose, with me pouring her a glass of something or other, and saying, “Here you go Mom, try this—it’s Chardonnay.”