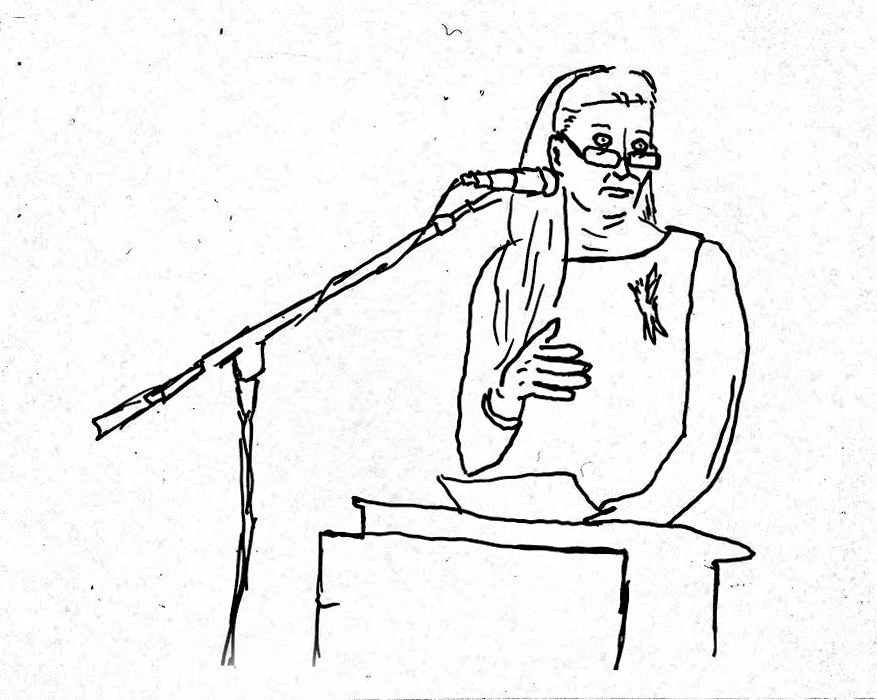

When Sarah Weiner, executive director of Seedling Projects and director of the Good Food Awards, spoke about her event’s impetus and goals, she put the spotlight on shifting paradigms. Weiner referenced Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Paul Simon, and 1960s nostalgia to articulate the point that change is possible.

Her romantic allusions were about challenging dominant orders. Small batch chutney is, in Weiner’s estimate, part of a larger cultural project.

To make the essence of her speech less minutiae and nitty-gritty, she pushed hard, towards a greater understanding of our food choices as true empowerment. She sang it like a sermon and asked us to go forth with the treatise of forks, spoons, and cups – conscious that choosing what we eat, how what we eat is made, and being informed about this is inherently political. Weiner’s words didn’t moralize: it was discourse about resilience, a script about the need to just keep going forward and toward in a way that honors what’s backwards and behind.

If we take Weiner, mastermind behind the GFAs, as the thematic architect of the ceremony, there is a push and pull in the content, a nice little meditation that relies on nostalgia and what our current moment is hankering for. Many of the presenters chanted the same idea: change, innovation, and movement. Katy Chang, representing the pickles awards and hailing from Baba’s Cooking School, really understood this forward/backward paradox when she said that food is about nodding to the past and embracing cultures, but staying in our time, with our seasons, and in our places. Others, like Vicky Allard, representing the preserves awards and hailing from Blake Hill Preserves, blushed about having the “Good Food Awards spotlight” shining on her small town of Grafton, VT.

For Dr. Zeke Emanuel, the Master of Ceremonies and Co-Creator of the White House Farmers Market, change hinges on making things public. He recalled trying to set up a farmers market for the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue and joked that if you try to build on Pennsylvania Ave, “you’ll find out a lot about who owns things.”

Again, we are nostalgically pulled to memories of the Commons and pushed to see shared ownership as part of our domestic responsibility. At home, we are all making choices that are about food, politics, and ownership ethics.

Dr. Emanuel cited the social, nutritional, and familial values of eating together and, most importantly, of knowing what we are eating. The Commons might not be Pennsylvania Avenue or farm land, but it might be information and our own kitchen table. We can know, to use his example, how raspberry jam is made, where our raspberries come from, and even what variety of raspberry is being used.

The new Commons is the new regionalism.

For Nell Newman, keynote speaker and founder of Newman’s Own Organics, innovation comes from understanding “organic” as more than a farming technique.

Newman referred to the natural world and her ardor, which stems from loving, since the age of twelve, birds. Birds enabled her to see the dangers of DDT and the necessity to promote a shift in balance, a return to recognizing that nature and the natural world require preservation. Looking at birds is how Newman started to understand that we can be generous and giving.

We were pulled to recall our own twelve-year-old selves watching tadpoles turn to frogs, collecting ladybugs, and feeling engaged with the world. We were asked to see the possibility that food can sustain that connection if it is organically and ethically produced. Newman’s presentation let us feel the possible change to good food as something we’ve already known; as something we’ve always known. I think most listeners would agree that her excitement was genuine and reaching back into our old selves was easy, comfortable, and tapped into the unspoiled politics of advocating for good, sustainable, and ethical food.

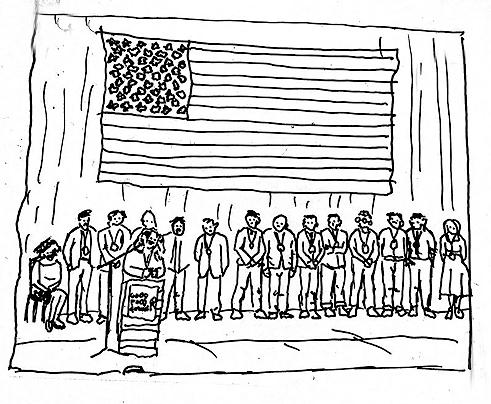

These early presentations and Weiner’s closing sentiments were the bookends of the Good Food Awards. With an American Flag in the background, the GFAs made themselves political.

They pushed food politics and reminded us that consumption is a political choice. They tapped into the populist overtones of “the people’s work” that values craftsmanship, artistry, the small batch. They gave contemporary meaning to how we eat lunch: does our charcuterie have a small footprint, give back as much as it takes, and offer transparency to the consumer?

Huzzah, GFAs. We should be pushing into a future that asks us to be responsible, because these choices will also make us resilient.

Any good genetic scientist will tell you that resilience comes from variation. It’s the same with our food and culture. What we saw at the Good Food Awards, what was “really good”, was that variation. Greg Woodworth, from Stony Brook WholeHeartedFoods, isn’t making an oil like any other oil; Stony Brook WholeHeartedFoods is making squash oils. Why? Because they can show variation by naming each oil after the variety of squash: roasted pumpkin seed oil, butternut squash seed oil, delicata squash seed oil, kabocha squash seed oil, and acorn squash seed oil. This is a nice representation of resiliency. Knowing and valuing the differences in taste, type, and season makes us accountable to preserve and connect with that squash.

Variation was a major part of the call to innovate. The innovation rested on understanding regional differentiation and identity. There were narratives of place and paeans to the distinction of what it means to be local. This is Weiner’s call for a shift: the local is the opposite of homogenization, the local is varied, the local is aware, the local is connected and engaged.

To some extent, the Good Food Awards felt like reading Gwynnie on Goop. The distances and miles of acquired goods were accounted for and valued; it as like a macrobiotic dream. The rhetoric was heavy with terroir, latitudes, and longitudes. It almost felt like a ceremony for cartographers or a great grandpa telling you how he used to walk ten miles in the snow.

Good. I’m glad it was so over the top in its appeal to place, folk, and collective sociology. Weiner is romantic, the GFAs are idealistic, but both of these are also right (and right on).

The micro level is extremely American, i.e.: states’ rights. We’ve always been a country that valued the local level. Andy Hatch, representing the cheese award and from Uplands Cheese, eloquently discussed that this new regionalism is about honoring differences and recognizing that they’re not really that different. He left the snow in Wisconsin to be in the California drought; “these are places that deal with seasons.” It’s the same. The micro level is intelligent because it helps us not homogenize, but empathize with how we are all on the same wheel, just at different stages of where it’s turning.

I know Sprudgies, you’re wondering, where does this leave coffee?

I’m not exactly sure.

Coffee’s regional identity is caught up, currently, in where the fruit is grown. The regional identity isn’t, exactly, happening stateside, although it could be. I can’t emphasize enough how important I think a book like Hannah Neuschwander’s Left Coast Roast is for trying to pin down regional coffee identity. Events like regional barista competitions all have the opportunity to showcase “place” instead of simply herding people into competition.

Deborah Di Bernado, representing the coffee award and from Roast House (located in Spokane, Washington, an agricultural town if there ever was one) focused on “having been there.” The “there” in this case being the coffee farm. This isn’t the same as regional identity because it’s still caught up in issues of imperialism and otherness. Can and will coffee begin talking about its regions of production, on both ends of the supply chain, in a new way? Are there roast regions? Should the fermentation process be discussed for producer regionality? How about for regional consumer preference? Can it be about the farms in a way that celebrates region more honestly and fully? Should coffee be concerned with this new regionalism at all?

In the context of the GFAs, coffee was a bit of an outsider (thematically).

Chocolate, which struggles the same way coffee does to present a local level, was better integrated. Shawn Askinosie, representing the chocolate award and Askinosie chocolate, brought it all back to the community when he discussed the “chocolate university” Askinosie operates for elementary through high-school youth in its hometown of Springfield, MO–designed to help children, often from disadvantaged backgrounds, understand entrepreneurialism and the wider world . He shared a story about a girl who studied in the elementary program and is now continuing to study and go to origin with Askinosie’s support. He asked, “Does it make our chocolate taste better?” And he answered “Yes.”

He’s right. It does.

Supporting the local level and seeing innovation as an act of intentionality that gives back, does make food “good.” It does give us our regional romance. And it one ups regionalism a bit by valuing a (as it says on their website) “world beyond [our] own.”

I look at an Askinosie bar and I know about the farm, the origin, and the ethical payments abroad. Those are all important parts of the “local” equation for artisan takes on global commodity agricultural goods, but they’re just that, parts. At the GFA Gala, Askinosie chose not to dwell solely on these farm-focused bits, instead treating them as what they should be–prerequisites for local, the assumed starting points for end-to-end stories of “local” that encompass ethical, enriching practices in the regions the goods are grown in, manufactured in, and consumed in. How can coffee get to that point too?

I know, you wanted to know who wore what and who wore it best at the GFAs. The truth is, Askinosie wore it best. Chocolate really clarified the concepts and showed us what’s at stake: people and places.

Kristen Orser-Crouse is an instructor at the University of California – Santa Cruz, with a focus on poetry and Russian literature. She’s written previously for The Rumpus, The Examiner, and Poor Taste, and is an accomplished author of original poetry, and has written previously for Sprudge on Duende Bodega in Oakland, and the importance of immigrant coffee narratives.