Our three-part series on barista health continues. In this second installment, Sprudge staff writer Alex Bernson explores the physical and emotional demands placed on coffee professionals. Read part one here.

In part one of our series on the health effects of working in coffee, we established a baseline understanding of the scope of these issues by looking at results from our reader survey. We found that 55% of respondents had experienced upper body repetitive stress injuries, 37% experienced persistent muscle soreness, 29% had experienced anxiety attacks, and 44% reported persistently high stress levels. These are real problems that are affecting people’s quality of life, and it’s the opinion of this writer (and this website) that the specialty coffee industry needs to approach these realities with candor and open dialogue.

To do that, in this second part of our series we dig deeper into what exactly is causing these issues, and what current industry best practices are. Though there are many health concerns involved in being a roaster, such as the noxious fumes from roasting, or doing production, such as extreme repetitive motion and heavy lifting, addressing every possible health issue of working in coffee is unfortunately beyond the scope of this series. I decided to focus this article specifically on the group that made up 3/4th of the respondents on our health survey: working baristas.

There are a lot physical strains involved in being a barista, and I in no way want to posit these articles as standing alone in a field of industry neglect. This is a subject that has actually received a lot of consideration by many upstanding people in the specialty coffee industry, and I was fortunate enough to be able to consult with a few in the course of my research. I’ve talked to Joe Monaghan, President of La Marzocco USA, Jennifer Prince, a longtime trainer at Stumptown Coffee and Liz Clark, a trainer at Gimme! Coffee to learn about the work their companies have done on the subject. The emotional strains of barista work is a much less studied area, but I think that sociological theory on food-service workers coming from my writing on cafe design helps to explain why an awareness of emotional labor is so important for ensuring long-term career viability.

Throughout this piece I attempt to point out potential steps that can be taken to combat these challenges. It is my hope that as an industry we can do a better job of first sharing the knowledge we do have, and then from there do more in-depth research to figure out how we can best ensure that working in coffee is a healthy, rewarding career.

The Physical Work of Making Coffee

In the late 90s, Starbucks approached La Marzocco for a very serious discussion: Starbucks was worried about the physical effects of barista work, and especially the potential for injury and Workers Compensation claims. Starbucks was conducting their own internal studies, but they wanted their equipment manufacturer’s perspective, and so La Marzocco reached out to an osteopath and a physical therapist for their perspective.

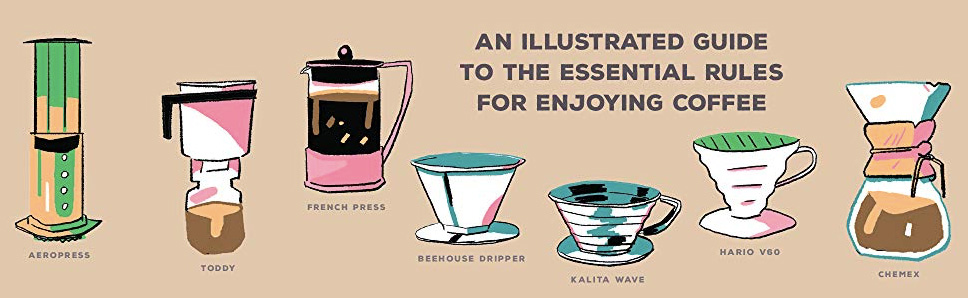

La Marzocco found the same things that Stumptown and Gimme! later determined with their own studies: there are many repetitive actions that baristas must engage in to make a cup of coffee, and though individual reactions to these actions vary, over time these motions can lead to injury. Chief among these is the action of tamping, but portafilter insertion and removal, knocking on the knockbox, lifting milk jugs, steaming milk, flapping dosers, and simply standing for long periods can all have negative health effects if done improperly. These actions can have serious effects on staff happiness and effectiveness, and injuries resulting from them qualify for coverage under Worker’s Comp.

Around the same time they were looking at health concerns, Starbucks was also getting interested in more automation of coffee work, and so La Marzocco developed the auto-dosing and tamping Swift grinder for Starbucks. Starbucks eventually decided to go whole-hog into the super-automatic mode of production instead of adopting the Swift, but the program LM developed for them was not a waste, in my opinion. The Swift’s volumetric dosing technology is extremely accurate—most accounts say between 0.2g and 0.5g accuracy, which is much more accurate than timer based solutions. La Marzocco knows the original Swift left some things to be desired in coffee quality, so they’ve partnered with Mazzer to create a new generation Swift grinder that marries the super-accurate dosing and tamping technology to a Mazzer Kony conical burr grinding platform. This new grinder is slated to be released in the first half of 2013 – rest assured you’ll be able to read and learn more about these new grinders right here on Sprudge as more information becomes available.

I am SUPER excited by the prospect of a viable and consistent auto-dosing and tamping grinder. I know that there are many people who will bemoan it as taking away some of the “artistry” of being a barista, but after months of physical therapy for an impinged nerve and strained pectoralis major in my tamping shoulder, I’m left with my mind firmly made up. If the cup quality is sufficient, I think I’ll take less injury (and honestly probably more consistently great coffee) over the perceived machismo and skill of manual tamping.

Despite these exciting developments, manual tamping will still be the default for a long time, and it is important to understand how to do it in a way that minimizes potential strain. Many quality-focused companies have put in time considering this issue, and have integrated their findings into their training programs.

Stumptown and Gimme! coffee have both gone the extra mile, reaching out to a wide-range of professionals, including physical therapists, OSHA consultants, massage therapists, as well as yoga and Tai-Chi instructors to develop in-depth health recommendations.

In general the consensus seems to be that the tamping action should be done using one’s core muscles, directing the force with a relaxed, not hunched shoulder, through an elbow at about 90 degrees with a straight, neutral wrist, into the bed of coffee with a properly sized tamper held between thumb and forefinger on the base of the tamper, with the handle of the tamper wresting against the fatty pad of the palm below the thumb. The exact way to achieve this varies from barista to barista, but setting your hips at an angle between 45 and 90 degrees from a counter that is at about 32inches and then lightly leaning into the tamp seems to be the best approach. Gimme! and Stumptown both point out that the well-known 30lbs of pressure that needs to be applied is much less than people think.

Gimme! and Stumptown’s training materials both go beyond just tamping. Stumptown emphasizes the importance of trying to work in the “area between your chest and hips, between your elbows. The farther you lift or pour something from this area, the greater the strain.” They also stress the importance of trying to relax your muscles and not stand in a stressed position while working, in addition to rotating through the tasks of register, machine, dishes etc. so that one isn’t constantly repeating the same motions. Emphasizing the holistic view, they suggest that you “Be aware of your body and routinely check in to draw your chin back, roll shoulders back and distribute weight evenly between feet and lower back. Avoid keeping your feet and hips planted and twisting from your midsection while moving shots or pitchers, or especially when lifting heavier items”.

Gimme! considered many of the same issues, and their work with a yoga instructor led to a focus on breath-work and “how to stay calm under pressure, whether internal (caffeine) or external (a line out the door). This allows for more self awareness, actual productivity and mental focus. All are the roots of avoiding injury and burn out in all parts of life”. Gimme! trainer Liz Clark told me that beyond taking a moment to just breathe, the most valuable take away from their work was the importance of stretching “often and in the opposite direction of the repetitive movement”.

These bigger-picture recommendations apply to other coffee jobs like roasting that involve physically demanding and repetitive tasks, and it is great to see reputable companies putting serious thought into what they can do to help their staff.

Another area of consideration for avoiding physical strains is the physical design of workspaces. Thick rubber mats are of course crucial in combating the fatigue of standing for many hours, but having well-thought out bar layouts with smooth, easy work flows and everything near at hand can also help reduce the strain of repetitive tasks.

I’ll cite an example from my own personal experience. As a former employee of Joe NYC, I’m impressed by their use of sandwich-prep style refrigerators next to the espresso machines for milk storage. The top openings had hotel pans placed in them, and then the open jugs of milk rested on top of these pans, keeping the cold milk at waist height, which removed the strain of having to constantly bend over and grab jugs of milk when prepping pitchers.

If you have other tricks of physical technique or workspace design that can cut down on repetitive strain, please share them in the comments!

The Emotional Work of Service

A big part of the work, and particularly the stress, of being a barista comes from the intense and constant “emotional labor” required in giving high levels of service in a fast-paced cafe environment.

In The Managed Heart, her seminal feminist work on airline stewardesses, Arlie Russel Hochschild describes emotional labor as “the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display; intended to produce a particular state of mind in others.” Another important sociological work, Erving Goffmann‘s “The Presentation of Self In Everyday Life”, calls this management of outward indicators of feeling “face-work”, explaining how in order to accomplish every-day social interaction we constantly switch in and out of different shallow face-level identity performances — performances that can be markedly different from the deeper emotions we are feeling. In giving “good service”, baristas must constantly engage in face-work to perform a specific identity that caters to the customers’ desires. This is what existentialists like Sartre and de Beauvoir termed “mauvaise foi“, or “bad faith” – as per Wikipedia, it’s “the phenomenon where a human being under pressure from societal forces adopts false values and disowns his/her innate freedom to act authentically.”

The “work” of emotional labor comes from the strain of switching into an identity at face-level that is at odds with one’s deeper feelings. Even if you are having a miserable day, when the next customer comes up to the register, you still need to create an enthusiastic, smiling, welcoming performance for them. And once you’re done serving one customer, no matter how frustrating the interaction may have been, you need to turn around and switch right back into your welcoming performance for the next customer. As a barista, you also need to carefully modulate your performance, reading your customers and knowing when they want a more enthusiastic welcome, when they want to talk about their day, when they want to hear more about the product being served, etc. All of this becomes particularly emotionally demanding because baristas must switch their emotional performance so rapidly and often—sometimes as many as 100 times in an hour.

This need to engage in many emotional performances in rapid succession could be particularly stressful due to the effects caffeine has on our emotional processing. A recent article in Forbes suggests that caffeine’s engagement of our adrenaline system “puts your brain and body into this hyper-aroused state, [where] your emotions overrun your behavior”, which decreases our emotional intelligence. The article suggests that caffeine’s disruption of our sleep patterns further inhibits smooth, stress-free emotional processing—all of which adds up to your standard highly-caffeinated cafe worker being prone to emotional stress before the first needy customer ever comes along.

In her work on servers in casual dining establishments, Karla Erickson explores how the requirement to perform deference to customers’ desires can be one of the main sources of burnout in service jobs. This is especially true the longer one works in the service industry—over time the stress caused by the difference between the emotions one feels inside and the external emotional performance required can become too much to bear. She found the successful career servers were the ones who were able to engage in what Goffman calls “deep-acting”, where they were able to cultivate genuine internal feelings of caring and compassion that matched their external emotional performance of concern for their customers’ needs.

Creating personable, community-oriented cafes where employees are able to genuinely connect with and care about their customers is one way that we can combat the draining effects of baristas’ emotional labor. Receiving tips is another well known way to deal with emotional labor—a barista’s wage is their compensation for their physical labor, while tips function as a welcome acknowledgment of and compensation for the emotional labor entailed in service.

Beyond encouraging communal good-will (and the tips that result from it), it is important to consider ways in which we can cut down on the actual emotional labor required of baristas. The Espresso Vivace service tip I wrote up is one example—by removing the unnecessary emotional performance of a bright and cheery “how ya doing!?” from every customer interaction, we decrease the emotional labor required of baristas and actually help encourage the genuine inter-personal connections that enable heart-felt, “deep-acting” service.

Another potential for cutting down on emotional labor comes from the increasing focus on a higher end, less “fast-food” service model for coffee. The new models people envision may lead to a lower overall customer volume as each customer receives more attention. This decrease in volume would help minimize the emotional labor of service by cutting down on the number of times that a barista needs to switch in and out of different emotional performances.

As our industry’s level of service evolves, emotional labor and emotional rewards will become an evermore important consideration. An overall stronger focus on the emotional needs of our workers will help us to find other aspects of our current service model that we can streamline to cut down on emotional labor, ways in which management techniques can support workers, and how we can best ensure that our company and industry cultures support deeply felt emotional commitments to low-stress, high quality service.

Join us Friday for the last article in our series. We’ll be looking in more depth at questions of caffeine over-consumption, blind-spots in current medical research on the subject, and will try to answer the question of whether or not a cup of specialty coffee has as much as 2x the caffeine as the average historical cup of coffee. We’ll also be looking at less understood potential health effects of persistently high coffee consumption and examining our survey respondents’ suggestions for how we as an industry can improve.

The comments are open.