It came as such a relief to finally set eyes upon the Collio hills (Brda in Slovene) on the border of Friuli and Slovenia, seemingly undulating forever into the distance. The sheer contrast of saturated shades of green on a clear day is a unique sight, and a marked contrast from the industrialized viticultural regions around much of the rest of Northeastern Italy. This was before Coronavirus changed life drastically in Italy, and indeed around the world.

We were positioned on the Italian side of the border in a hamlet named Linzuolo Bianco, nestled in Gorizia’s Oslavia district; a grapevine-friendly microclimate that at this point in history is famous for its extended skin-contact orange and amber wines. Home to the likes of Dario Princic, Radikon, Fiegl, and La Castellada, this tiny town touts top quality. But to me, if asked to pick the most enigmatic and esteemed winemaker and farmer of the few, from the mid-’80s to this very day, it would have to be Josko Gravner.

Within the natural progression of popular pieces of culture suffering the loss of their idiosyncrasies over time, orange wine (Gravner prefers the term “amber wine”) and wines made in amphorae have grown more ubiquitous—not to mention popular—over the past few years. In turn, winemakers worldwide have this consumer demand by turning to orange wine, and the vinification techniques associated with it. All the while Josko Gravner has inadvertently maintained his legacy as a pioneer. He is popularly considered the first winemaker outside of the nation of Georgia to make skin-contact wines in amphorae, all the while continuing to innovate and leave his craft in a constant state of metamorphosis.

Gravner grew up where he continues to live and work today. He joined his family business in the ’70s and became an acclaimed winemaker by the ’80s after modernizing his cellars and increasing production—despite his elders’ advice. After a trip to California in 1987, his world was turned upside down out of sheer disappointment from the industrialization and commodification of wine that he’d witnessed. This was a turning point for him as a winemaker. He removed all the majority of modern technology from his cellars and farm, reconsidered his agricultural techniques, and never looked back.

In 1996, a tremendous hail storm-ravaged all but roughly 5% of his Ribolla production, and he took the opportunity to conduct an experiment. He vinified 20 hectoliters with extended skin macerations and without inoculating the wine with selected yeasts.

Once the wines were released, Italy’s most revered food and wine guide, Gambero Rosso, rated this vintage as a disgrace to his previous work. This resulted in the loss of his reputation and the majority of his domestic and export sales had been canceled before any of them had even had the chance to taste the new vintage.

Josko Gravner is a man driven by belief, and he felt strongly that this then-novel approach made an excellent and intriguing beverage. Instead of letting these continuous gut-punches completely destroy him, he stood passionately by his practices, and over time the rest of the world has caught up. His work is now synonymous with quality, and the orange wines he makes have in turn inspired a generation of winemakers around the world.

After realizing a trial batch of wine that he vinified in terracotta amphora at his family’s 300+-year-old home just over the Slovenian border, he decided to travel to Georgia in 2000 in pursuit of purchasing more “Qvevri,” or amphorae, to bring back to Friuli to make his wine. By 2001, he had the initial 11 of these handcrafted amphorae transported to his cantina, buried them beneath the soil, and continued making all of his wines this way.

Some would argue that this was just the beginning of the Gravner story.

I stood with Mateja Gravner, gandering out westward from the highest point of her family’s iconic “Runk” vineyards, as she explained all the ways in which the land before us informed what was in these famed bottles. This was where her father, Josko, developed most of his farming expertise and discovered a reverence towards the Ribolla Gialla vine.

Following the few horizontal rows of vines directly in front of us, two skew hill crests pointed towards different vantage points in the distance. A superabundant extension of the forest at the bottom of the overall hill tunneled through the valley of vines between the two opposing hill crests; a visual testament of their heightened attention to maintaining the biodiversity in their vineyards. Although this is only one of their six stunningly beautiful vineyards (it was seven vineyards up until 2012, when they converted one into a neighboring forest), this was where many of Josko’s agricultural trials and theories proved fruitful to his style of production.

We walked downhill towards the first of their many man-made ponds in the middle of the vines. Gianfranco Soldera, the heroic winemaker of Montalcino, had introduced Josko to the builder of these ponds that he’d previously employed for his own Tuscan vineyards. Mateja explained that specific species of fish and plants are very important to maintaining a relatively clean and odorless environment in the pond, highlighting the fact that having any or all wildlife in the vineyards can be counterproductive to a balanced and healthy ecosystem.

We all took shade from the heat of the pre-harvest sun beneath the sole apple tree by the pond. As groups of tiny birds darted in and out of the miniature amphora-shaped birdhouses hung throughout the branches, Mateja preemptively informed us about the foreseeable future of the family business before our scheduled interview with Josko, as it was clearly a sensitive subject. Her brother Miha passed away 11 years ago from a tragic motorcycle accident in Croatia at the age of 27. He had grown up working side-by-side with Josko, and was the impetus behind their biodynamic conversion. As the projected heir to the cellars and vineyards, this came as a massive hit to the trajectory of the family business.

With her experience and studies in communication and media, Mateja changed course and joined the company to help where she could. She quickly grew into her present, integral role as marketing and communications director. Her 25-year-old son Gregor, who we had the pleasure of later meeting in the cellars, had recently started working full time with Josko. She mentioned that while it’s not always easy to work with Josko, and that the role was never expected of him, Gregor takes to the labor ambitiously with determination, fascination, and a sense of honor to the decades of work that preceded him.

Before we all headed back a quarter mile down the road to the Gravner home and cellars, Sam and I quickly picked and tasted grapes straight from a few random Rkatsiteli (native Georgian grape variety) vines that were scattered through one of the vineyard rows.

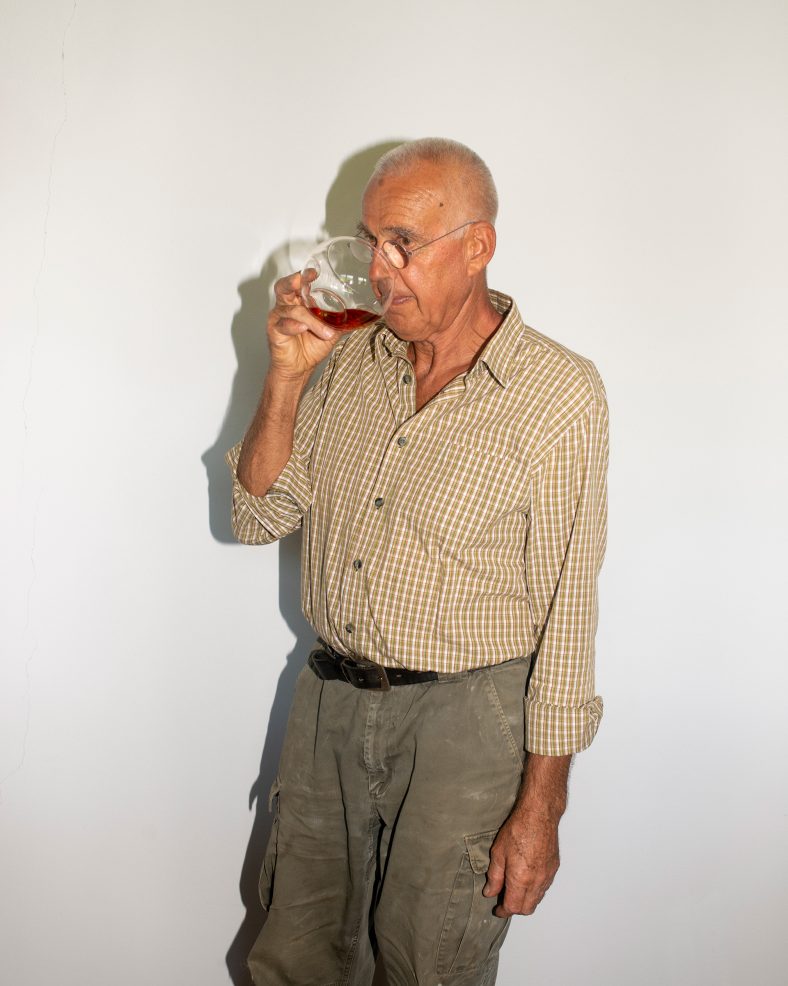

This was not my first visit to Gravner, but it would be my first time meeting with Josko. When we first arrived at the house, he was out front in farm wear, dripping in sweat, and missing all the common accouterments that signify a revered winemaker whose bottle prices start at 50 euros. He greeted us with a humble smile, said nothing, and quickly went to change into something more comfortable. Because of it being an extremely busy time of year and because of his initially stoic nature, I anticipated quick and simple responses to my few questions. Imagine our pleasant surprise when this opened up into an hour-long discussion.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Josko and Mateja, thank you so much for hosting us. I understand that you haven’t been fond of the term natural wine for quite some time, and yet, Gravner is often referred to as a natural wine pioneer. How does this sit with you?

Josko Gravner: We are not big fans of definitions or labels because all of them, over time, take on meanings that have nothing to do with their origin and initial intention.

For me, what I do here is not fashion. Those who just make orange wine because the market suggests it will most likely focus elsewhere when the fashion changes, although I am convinced that there will always be many producers out there that will stand with their feet on the ground while they make wine. Yes, I make my wine with all considerations towards nature, and yes it is clear that there’s a difference between industrially-made wines and good wine. Past that, what defines a natural wine?

I don’t like to talk about natural wine, and especially not when suggesting a wine only because it’s natural, as it implies that all other wines have a questionable relationship with nature. I make wine, wine as simple as possible and at this moment, my cellar operates with three kilowatts of electricity, or rather four, because I recently added a more powerful peristaltic pump. But I’m proud of this, as I should be, right? But I’m not convinced we are defining natural wine this way.

Following fashions also means being more attractive to the market—which requires a certain type of product that we are not focused on. In the end, it is not for me to claim a trend or responsibility for some movement for nothing because I simply make wine that I believe in and that I like to drink.

Mateja Gravner: And to do something because you were convinced by someone or a market and you don’t understand the reason, doing so doesn’t have the same effect on you or on what you make and do.

One prominent and controversial element of “natural” winemaking is the use of sulfur to preserve the wine. Why is it important for you to use sulfur during winemaking?

JG: In my opinion it is essential. In the ’90s my goal was to eliminate sulfites as well, but I realized that using nothing did not work. It was not an untested ideology or theory I decided on.

During the fermentation of the grape must with indigenous yeasts, the must produces small quantities of sulfites anyway, so in the end, it doesn’t make sense that very small amounts are such a serious act. In those years I made winemaking tests with very few added sulfites and each time I found that the sulfites that I added relieved the wines in comparison to the aggressive results I found when not adding any at all. But I will say that the wines with very small doses of sulfites were far superior to those I used to add larger doses. Knowing how to make wine includes understanding how to use sulfites by adding the bare minimum.

The Romans, already over two thousand years ago, had understood this concept and had started adding sulfites in their wines to improve their quality.

Now there is a fear of sulfites and many consumers look for wines made without adding sulfites, but they do not look at fish, fruit, vegetables (including organic); all preserved with products bearing the initials E252. Of course, this does not mean that the sulfites must be added with a light heart but must be considered as a whole of everything we eat and not just demonizing wine with sulfites added.

After seven years of aging, the wine is bottled with about 60-70 mg/L of total sulfites. Certainly, if I bottled after two years I could reduce the total quantity of sulfites, however seven years of refinement to mature the wine can require (in the decanting phases) a few more milligrams of sulfites. I really believe that it is worth having the milligram more of sulfites in wine that has truly matured in comparison to a wine that was made in a hurry, maybe in steel, and bottled three to four months after the harvest.

After your trip to visit California winemakers in 1987, you returned disillusioned and conflicted about the future of wine. Since that point, you’ve made an unusually large tally of drastic changes to your family’s historic cellars and vineyards.

JG: Yes, to get to the source of the wine.

Was it something from that trip that drove you to make these changes? What was the reason or what were your thoughts when making these alterations to your routine?

JG: Ultimately I try to understand and support nature, without forcing it to allow it to express itself better.

I started making wine after my father, but he only used big barriques for winemaking. We moved to fermenting in stainless steel, but it was clear to me that cellar temperature control was also needed because the tanks are susceptible to fluctuating temperatures. If man has been making wine for five or six thousand years, it is clear that it was done without electric temperature control.

From there I went to eliminate the new oak barriques. For some reason, the barrique has been used in regions where there is talk of the importance of terroir… but then the vessel is used to add tannins and add the toasted note of the barrique that covers any distinct aspect of terroir. From that then I went to the wooden vats for fermentation and maceration, and then from the wooden vats for maceration to the amphorae. At that point, I felt I had closed the circle of my searches.

When new technology that did not yet exist is made the means for success, it is born, and then dies, as another new one that’s even more “useful” is born. The previous conventions will always be put aside. As a consequence, I said to myself, “Let’s go and look for clean water in the river; not where it meets the sea, but the clean water from the mountain; from the source.” The amphora was born 5,000 years ago, and in those 5,000 years, with all of these “innovations,” we are past the mouth where the water is already polluted.

During my trip to California in ’87, I understood how the world of wine works. [Things like] market research… I do not want to offend anyone, because it was a new world of wine in California where they tried to capture the attention of the Coca Cola consumers, and therefore market research was a priority at that moment. I saw that there were even schools that were financed by chemical and oenological companies that had the need to create young graduates who in the end became their agents of sale of products that shouldn’t be used for wine.

On top of that, where there was once corn, a farmer randomly decided that they wanted to build vines. In my opinion, there are places suitable for viticulture and places not suitable. It’s clear to me that the vine either makes it on its own or if not, change the crop. Besides the atrocities of commodification and manipulation I witnessed in cellars, there was also irrigation used everywhere in vineyards and chemical sprays being used to prevent indigenous species from occupying their own terrain; a state of complete disregard towards nature.

At that moment I said, “I want to make wine, not market research. I want to make wine that is good, and then there will be a consumer who’ll agree with us.”

I approached this piano piano [slowly, slowly] because going against the current to do things that the world does not accept willingly is difficult, isn’t it? Especially for sales. I said it before but it is very important that wine must above all please me. If I like it, it has already taken a good step, but then this is also to be understood by the consumer.

You either become an industrialist or you are a farmer. If you are a farmer, you have to do things as they should be done, without intervention without changing the raw material. This involves an immense amount of work in the vineyard, waiting for the harvest for a long time, and harvesting only the highest quality of your production.

For example, it’s clear that the 2011 vintage is a great vintage, but 2012, which is less than a vintage because we tried to collect the small amount that 2012 gave us, is nothing less. I realized that all the vintages are great, even when the hail arrives because we have an open-air factory… you have to be ready to accept everything without intervening.

You add layers of beeswax to the inside of your amphorae as observed in traditional Georgian winemaking practices. In your opinion, what is the benefit of this?

MG: It is simply an unnecessary loss of wine quantity: unlike wood, the clay does not stabilize the wine, and the wine will continue to pass through the pores in the amphora. Beeswax allows some oxygen to enter the amphora and during fermentation, not to mention that at least six punch downs per day are done so that the fermenting yeasts always have enough oxygen.

How many amphorae and barrels do you currently employ?

MG: We now have a total of 47 amphorae (between 1,300 and 2,400 l each).

In the aging cellar we have four 7.000L vats, four 6,000L vats, four 4,800L vats, three 4,000L barrels, eleven 3,400L barrels, one 2,000L barrel, nine 1,300L barrels, and eight 1,000L barrels.

In 2007, you made the decision to not release any wines until they had aged seven years under your care How did that affect the winery over the next seven years? What kind of sacrifices did you have to make to mitigate the annual sales loss for seven whole years? Was it a spontaneous decision or how did you prepare for such a business challenge?

JG: The decision to extend the bottle refinement was made in 2005, when the first vintage fermented in amphora, 2001, came out for sale. Since then, the release for sale of the following years has been, slowly and gradually, elongated, to bottle the 2007 vintage in 2014.

It was an important decision, but the fact that we temporarily distributed the economic commitment allowed us to face it. Let’s not forget that such a long refinement greatly increases the risk that something goes wrong and that the selection and processing of the grapes must be meticulous.

There is a surging market interest in amphorae-made wines, and it’s starting to seem like most Italian natural winemakers have at least one amphora in their cantina. As one of the initial modern advocates for the use of amphora in winemaking, how do you feel about all the hype?

JG: Fashions have always been and always will be. Those who use amphorae because they are convinced of their value will continue to do so, those who use them for fashion will soon move on to some other container or production system. It is a matter that concerns us little, in the end, the quality speaks for itself.

The fact that there are more manufacturers to make and use them is good. We are not interested in being the only ones, and for the consumer having more choice is always good.

Alexander Gable (@mrgable) is a freelance journalist based in Milan. Read more Alexander Gable for Sprudge Wine.

Photos by Sam Youkilis