If “the Glory of God is a human being fully alive,” as the motto of New York’s Church of the Heavenly Rest has it, what better to serve Him than an Australian-inspired cafe on the premises serving espresso, pour-overs, and avocado toasts?

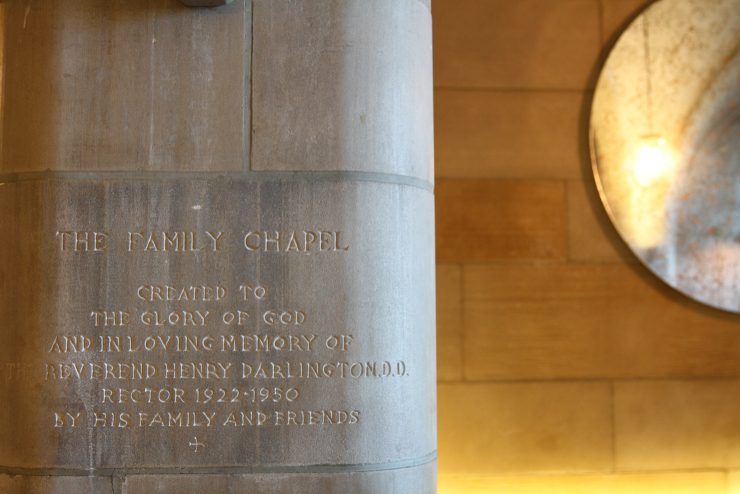

In summer 2015, the New-York-based coffee company Bluestone Lane, which got its start inhabiting nooks of lobbies in coffee deserts like the Financial District, opened its seventh location in its most unusual space yet: a chapel. The church it abuts is no desacralized place on its way to a condominium future, but an active Episcopal congregation.

Set at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 90th Street on the Upper East Side, the church is washed by a tide of tourist foot traffic: the Guggenheim Museum is one block down, and Central Park lies across the street. The surrounding neighborhood of Carnegie Hill has been sedately moneyed since the time of Andrew Carnegie, the nineteenth-century steel magnate, whose widow sold the land on which the church is built.

The church’s rector since 2013, Reverend Matt Heyd, says the idea for a cafe dates to 2009, when a former priest, Reverend Elizabeth Garnsey, suggested a new use for an old chapel with a separate entrance. “A key part of faith is hospitality,” observes the youthful Heyd, who seems slightly caffeinated himself. The church wanted to signal that “its doors are open to the community.” It also saw a potential revenue stream, something few New York churches can afford not to think about.

The Heavenly Rest Stop, as the cafe is known, was opened in 2009 by another operator. When its five-year lease ran out, the church rethought the concept, deciding to add table service and “more sense of a menu,” Heyd says. After scouring New York for a new tenant, the church approached Bluestone Lane, which had grown from its office-lobby origins to open a cafe with food service in Manhattan’s West Village.

Heyd found Bluestone Lane’s owners “cool and entrepreneurial,” and saw in them a “passion for hospitality.” The church appreciated that Bluestone Lane “paid their workers a living wage” and was willing to “give back to the community” financially, though exact terms for outreach have not been set.

Bluestone Lane signed a ten-year lease and was given the chance to redesign the chapel, a job it undertook stylishly with the help of Caswell Design Group. White sidewalk tables and chairs flank the entrance, a Gothic arch with a heavy glass door leading into a vaulted stone space. Brass lighting fixtures, antique mirrors, and clean-lined wood-and-metal furniture set the tone for the cafe, which is graced by a skylight, plants, and a pair of brushy abstract watercolors. Tables and benches are set into alcoves, and a communal table runs down the middle, leading the eye to a white, three-group La Marzocco Linea PB.

The cafe is a handsome reworking of a space that served in past incarnations as a library and a place for brides to wait before their weddings. In its mingling of Gothic and modern elements, it feels suited to the church itself, whose silvery Art Deco touches make it seem the product of a dalliance between the Chrysler Building and Westminster Abbey.

Bluestone Lane serves espresso from the Melbourne roaster Niccolo Coffee and pour-overs from San Francisco-based Sightglass Coffee. True to the church’s plan, there is table service and a menu of light dishes including salads and toasts like the Avocado Smash. At $13, it is priced for the neighborhood, but with heirloom tomatoes, tahini, feta, and Balthazar bread, it is making an effort at least.

Rev. Heyd finds that while the original Heavenly Rest Stop drew a mainly tourist crowd, the revamped cafe is gaining popularity with locals, ranging from museum employees to Fifth Avenue dowagers to students from nearby private schools.

Though New Wave coffee and the Holy Trinity might seem curious bedfellows, this is not the first food business run at an active New York church. Another Episcopal church, St. Bart’s on Park Avenue, operates a restaurant and bar popular among midtown office workers. Wine may be the original Christian beverage, but coffee feels just as ecclesiastically apt, its scent having lingered over so many after-church coffee hours. Here, thank God, the coffee is not from a percolator.

It seems unlikely that the cafe will generate new parishioners for the Church of the Heavenly Rest, nor is it meant to. Many pass from the cafe through a door connecting to the church proper, but most appear to be in search of the bathroom, not the Lord. That is fine by Rev. Heyd, who says simply, “I hope people always feel invited to the church.”

Alexander Henry is a writer based in Brooklyn. Read more Alexander Henry on Sprudge.

Photographs by Liz Clayton.