My love affair with Indonesian coffee began early, while I was new to the coffee industry, and still coming down from the seething iconoclastic urges of my teenage years. My fellow baristas loved Ethiopian, Colombian, and Brazilian coffees, but something pushed me towards the bracing earthy and herbal notes that took the foreground in coffees from the Indonesian archipelago. That same something later pushed me towards things like Laphroaig whisky, chili-addled delicacies, and Kretek clove cigarette lung torpedoes. But those are stories for another time.

Like anyone, I began to appreciate the more nuanced flavors of coffee only after tasting coffee day after day. Victrola’s Bolivia Juan De Dios Blanco and later 49th Parallel’s Ethiopia Beloya Micro-Lot #3 opened my eyes to the breadth of flavors that can be present in coffee, and I always looked forward to tasting a new coffee with my coworkers and friends. Thomas Surprenant and Samuel Lewontin were my consistent tasting companions, and together we spent a fair amount of time staring blankly out of windows in awe of the sweet emulsions that had just graced our papillae. They were good days, but it was rare indeed that all three of us agreed that an Indonesian coffee was blowing our mind.

Some Indonesian coffees continued to pull at my tongue-strings, however. In particular, Lake Tawar, Blue Batak, and Toarco Jaya coffees were consistently good from year to year. To a younger me, these coffees vindicated my positive view of Indonesian coffee in general. Later, I realized that I would need to take a more critical stance to understand what it was about these coffees that drew me in, and to provide me with material for starting a true dialogue with my peers. All this eventually led me to Indonesia to seek out answers for myself.

My travels confirmed what I knew to be true in the verst place—that the story of coffee here is nuanced and manifold. Very similar to my experience of Indonesian culture, I knew there was always an exception to each rule, and more wiggle room than even Big Freedia could ask for. In recent years in particular, there are players in the Indonesian coffee game that change people’s impressions and expectations. To find out more, I’ve spent months traversing the islands of Indonesia, seeking out the places behind the well-known names.

Giling Basah

Stepping onto the street in Medan, affronted by a million-piece horn section erupting from the cars, my fight or flight reflexes kicked in. Luckily, a good friend from my Q Grader coffee tasting certification course was there to whisk me away to a cupping as soon as my boots hit broken pavement. A wide array of coffees that would look atrocious to a green grader were spread in front of me; most were quite tasty, and all were prime examples of the Giling Basah processing method.

Giling Basah, or wet hulling, starts with freshly pulped coffee cherry, which is submersed and fermented overnight in whatever vessels may be available (or dry fermented if there is a lack of clean water). After fermentation, the coffee is washed, but sometimes not. The best place to dry coffee in many undeveloped areas is the road—a wide, flat, space clear of plants is especially hard to find in mountainous areas of the tropics, where bamboo can grow up to 35 inches in a day. So the coffee is spread out to dry to around 40-50% moisture; only in the best cases is drying done on a patio or para-para covered tables.

At this point, the coffee is called Gabah, and many times it is sold directly to collectors. The collectors will then dry the coffee further (until about 25%), and remove the parchment with massive hullers while still wet. The resulting still-flexible coffee is called Labu, and it is often dried to 15% moisture over a 5–7 day period, before shipping to Medan for further drying until 12% moisture is reached. The Labu stage is particularly testy, because mold can grow very quickly at this point.

Giling Basah processing, and its potential for variability and flavor defects, is what many specialty coffee people think of when they think of Indonesia’s coffee. But the story of Giling Basah I just told you is as much a story of the economic, geographic and social realities of these places as it is a story of the potential behind wet hulling coffee, Giling Basah.

Tiga Raja Mill, Silimakuta, Sumatra

I wanted to see an example of Giling Basah done in a controlled environment, and done well. To this end, I was introduced to Leo Purba of Lisa and Leo’s Organic by Stephen Vick, lead green coffee buyer for Blue Bottle Coffee. Lisa and Leo’s processing facility, Tiga Raja, is located just outside of Saribu Dolok in Silimakuta, Simalungun. Tiga Raja is majority owned by Five Senses, an Australian specialty coffee company based in Perth and Melbourne.

[Sprudge.com is proudly partnered with Five Senses. You can learn more about their work with Tiga Raja here. -ed.]

My conveyance from Medan to Saribu Dolok was swift and uneventful, aside from a very pleasant conversation with an older couple who wanted to know more about what religion is like in America. The air got cooler and cooler as we climbed, and I arrived a short time later in the regional wet market, where Leo Purba picked me up. Since he originally hails from this area, Leo is just as comfortable speaking in Bahasa Indonesia as he is in a heavy Boston patois (he attended university in Boston). We head directly to Tiga Raja where coffee was being hulled, dried, graded, and sorted. Dangdut blares from a boom box while twelve local women pick defects from piles of coffee. Gabah parchment and freshly hulled Labu coffee is pulled into rows by young men wielding cinnamon-wood rakes. Daisy and Oshin, their faithful dogs, keep watch over the gate.

Tiga Raja has another six tons of wet parchment arriving in a couple days, and Leo is hard at work with a moisture meter while Lisa is rotating her dry process coffees from Ladang Isabella. Later, Leo and I drop by the church co-op he works with, Talenta, where Gabah is collected to be brought to Tiga Raja. Here, parchment from member farmers is accepted or rejected based on quality; Leo shows me some good parchment (Gabah Super), and some that will return to the local market. The good parchment smells of ripe banana and beautiful fruit, while the rejected Gabah smells of leather and mustiness, and still has bits of pulp attached. Though the difference is clear, the parchment is checked again when it arrives at Tiga Raja at 11:00 p.m. the next night; we find two bags with a certain bovine quality, and they are sent back.

We finish around 2:00 a.m., and head back to sleep. Leo gets up the next morning at 7:00 a.m. to oversee the workers at the mill; he does this about twice a week during harvest season. So do all of the folks who work at the mill. Leo takes a break, and I join him at the local wet market where we buy twenty fish, limes, and a good amount of garlic to take back for the workers’ late dinner.

A few days later, Leo and I head to Medan to pick up GrainPro bags to safeguard the green coffee as it ships, drop off some parchment, and avail ourselves of the services of the largest post office I’ve ever seen. Lisa and Leo make this trip often, and will actually follow their coffee to port until it is sealed in a shipping container.

It can’t be said enough: having seen the amount of hard work that goes into this process leaves me humbled. From smallholders who pick and process the cherry to parchment, to seeing a small warehouse in Medan that ships twenty containers of coffee per year, there is a dizzying array of things that can go wrong. That having been said, the coffee is delicious, herbal, and mellow, with an intriguing mulberry note, which Leo tells me is peculiar for Simalungun. The hard work pays off in the end when this coffee is in the cup of a person who sips it and thinks “Gee, maybe I was wrong about Sumatran coffee.”

After braving the masticating metal monstrosity that is Medan macet (traffic), we have completed our tasks. Leo and I sit at OnDo, a Batak restaurant with some of most delicious food I’ve had in Indonesia. The flavors here are something like those I find in Sumatran coffees back home; heavy bodied barbecued pork in blood sauce, curried cassava leaves with a profundity of spices, and fish in a brightly citrusy red sauce that I keep coming back to taste. The strong flavors that drew me here are replete in the regional cuisine, and once again I find myself staring out a window, tastebuds aflame.

P.T. Toarco Jaya

Rantepao, the capital of the North Toraja Regency is as close as you’ll get to the Wild West in Indonesia. The country and western twanging from trucks provides an apt soundtrack to a rough and tumble coffee prospecting scene reminiscent of the gold rush.

The local coffee trading system in Tana Toraja is based off a system of weekly local markets, with the largest and most central at Rantepao’s Bolu Market. Here you can find local and regional coffee collectors buying by the heaping liter, and selling by level liter. They make a game of it, with sellers trying their best to level off the liter container, and buyers reserving the right to throw in a handful edgewise.

Perhaps the most well-known of the coffee buyers is P.T. Toarco Jaya.

I met H. Jabir Amien, Director of Toarco Jaya, at a trade show in Rantepao. I immediately gravitated to the Toarco Jaya booth with its shiny V60 pour-overs and Takahiro kettles providing counterpoint to the dusty field, and sidled up for a taste. Fortunately my compatriot was already acquainted with Pak Amien, and was able to introduce us. The three of us talked for a bit, and he graciously agreed to let me visit the farm and processing facility at Pedamaran.

This was no small invitation, as it seems many people in Rantepao have always wanted to see what happens behind the guarded gate at the region’s most developed coffee processing facility. We pass a fanciful yet anatomically correct statue of a water buffalo, and make our serpentine way into the mountains outside of town towards the facility. It should come as no surprise that many rumors surround such a place, but at the end of the day it is simply a well-built, well-maintained processing station.

The coffee here tastes different from other Indonesian coffees, and for a very good reason; it is not processed like any other Indonesian coffee. Here, coffee cherry is immediately floated to remove defective cherries, run through demucilagers, and washed thoroughly through a series of flues that reminded me alternately of a mining operation and a fantastical chocolate factory of some sort or another.

Pak Amien is decidedly more Gene Wilder than Johnny Depp, however. He is notoriously hard to pin down, and this made me feel even more privileged to be in his presence here in Toraja. It is clear that he feels in his element and is proud of the work that goes on here.

He directs my attention next to the drying floor, where parchment is sun dried. All of it looks gorgeous and clean. The largest volume of parchment is finished off in giant Japanese gas-powered driers, and their whirring draws our attention next. Beside the array of giant drying robots is a Colombian-made barrel dryer powered by heat from burning husks (the remaining parchment from hulled coffee). Pak Amien explains that they are still experimenting with how to use this contraption to its full potential.

Finally, we head to the hulling and grading area, where a Rube Goldberg-esque system of chutes, screens, and vibrating mats twists itself down to a large room full of sorting stations. If this room were in full production mode, one could expect to see at least ninety people sorting out defects. Today, however, the sorting gets finished in short order with only five people separating out defects.

Our last stop is the cupping room, where I am privileged to taste the three varieties of coffee they have—all differentiated by grading. There is a A, AA, and PB. All are very clean, citrusy, and sweet; I prefer the AA, with its lightly syrupy body and something vaguely tropical in the background.

None of this happened overnight. P.T. Toarco Jaya was started by the Japanese firm Key Coffee in 1976, and much research and investment has happened in Toraja in order to get it to where it is today. Toarco provides seedlings, farmer training, depulpers, and some of the roads built nearby. Regional buying stations were also established, and their coffee is subject to rigorous quality control. The result of nearly forty years of hard work is what you can taste in this coffee.

As Pak Amien relates, the original method of processing in Toraja was actually fully washed coffee. Due to increased demand for the Giling Basah flavor profile, many companies have asked producers to convert to this method, much to the dismay, I imagine, of someone who has worked so hard to produce such clean coffee.

Toarco Jaya has extended its influence over much of Toraja, and has definitely made a name for itself in cupping labs and on retail shelves across the world. Indeed, it’s a name that brought me all the way across the Pacific. I feel blessed that I didn’t even need a golden ticket for entry.

Ketut Jati, Bali

Residing in Bali has its benefits. Sunny days, the sound of crickets at night, and the gamelan ringing through the rice fields any time at all. Bali also has a good amount of coffee, the majority of which goes to local market. However, some coffee makes it across the water, and into the waiting cups of specialty coffee drinkers.

The first coffee I tasted from Bali was a very vibrant dry processed coffee from Kintamani. The first year I had it, strawberry sweetness and heavy body dominated. The second year, something went wrong, and the coffee exhibited what we fondly used to refer to as “dangerberries” at the cupping table. It became a little too wild, and I didn’t see Kintamani coffee grace the cupping table the next year.

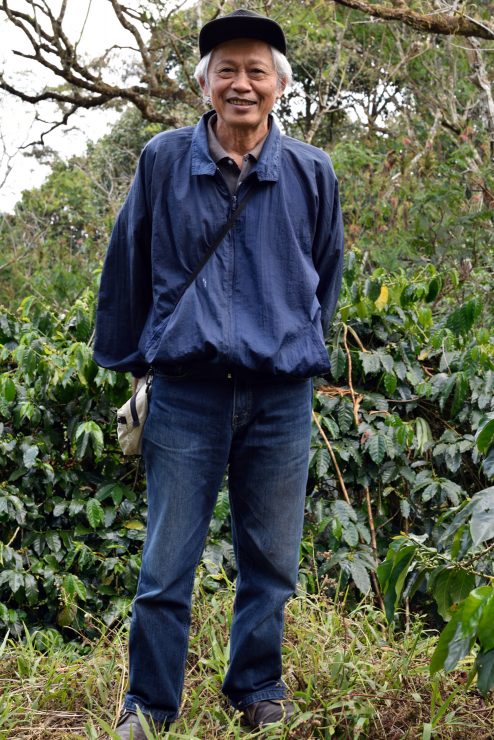

Living in Bali, I had to observe some of the coffee growing territory and see just how wild it could be. My good friend Thomas introduced me to Ketut Jati, who runs a processing station at MPIG Kopi Kintamani Bali. I took my trusty 100cc motorbike up into the mountains. Finally, I made it around the last bend and found Pak Jati busy sorting coffee with his crew.

He was kind enough to take me to his farm on his decidedly larger motorcycle. As roughly 3g of force pushed me into the saddle, we whizzed by a huge number of coffee shrubs at speeds that would put the Millennium Falcon to shame. We arrived at his plantation, and delved into the underbrush.

As is the case in much of Bali’s arabica growing territory, the coffee is intercropped with oranges, which provide consistent income while farmers wait on the coffee crop. Oranges can be much more profitable for farmers here, and Bali is in danger of losing most of its coffee shrubs to orange trees due to this fact. The drawback to this strategy is that oranges are even more dependent on fertilizers, pesticides, and antifungals than coffee. Pak Jati is hedging his bets by planting both, however, and who could blame him? The coffee market continues to fluctuate, much to Indonesia’s chagrin.

We pick some cherry ourselves, and remove suckers from branches while we’re at it. Pak Jati gives pointers to the other pickers, advising them to pick only the red cherries. We toss overripe cherries and the suckers into impromptu compost pits between trees that will eventually be the site for new seedlings. Time passes freely, and though I’m sweating, I don’t notice how quickly the sun is moving overhead.

Pak Jati drives us back to the processing station, and we check out the various projects he has going. In his covered drying area, he has fully washed and honey process coffees drying. There is also an area outside for dry process (natural) coffees, but that is mostly for the floaters and other unripe beans to be sold at local market. He has some parchment coffee to process, and we load it into the huller with the help of his two coworkers. Afterwards, he puts it through a small grading machine to weed out any fragments or “elephant beans.”

Though Jati’s space is smaller in comparison to some I’ve seen in Indonesia, the size of Bali itself is only big in name. Living here, I constantly have to remind myself how small and separate it is to the rest of the archipelago. Bali will continue to distinguish itself, but the main struggle for this island is to create a flavor association in people’s minds that rivals that of its larger-than-life name. I Ketut Jati is one of the leaders of this push, and I hope to see his coffees on the cupping table in the future.

* * *

Many obstacles lie in the way of Indonesia’s advancement in the ranks of specialty coffee.

Basic infrastructure problems make the kind of centralized processing that is happening in Eastern Africa and Central America very difficult. Large and growing mass-market demand for the Giling Basah profile (though its flavor is problematic for specialty coffee) leads farmers to adopt that processing method; from Java to Flores, I heard about people adopting this process to satisfy demand in Medan, where the coffee is shipped to and relabeled as”‘Sumatran” for export. Furthermore, this practice stymies efforts to promote the idea of regionally specific flavors.

Though there isn’t as large of a market for coffees from Indonesia’s East—Bali, Lombok, Flores, and others—there may very well be in the future, if people are given the opportunity to associate taste with particular origin. Even the current conception of what a Gayo, Mandheling, or Lintong tastes like is wildly generalized and self-referential, as the coffees labeled as such are only done so in relation to their flavor profile. Leo posed an example in one of our discussions; many coffees from Saribu Dolok market are sold off as Lintong coffees, though they are distinct both geographically and in terms of flavor. A Jimma is different from a Harar, so why can’t a Simalungun work to be different from a Lintong?

Sumatra alone is a big place. Indonesia is the world’s third largest producer of coffee, and holds massive potential as such. Many development success stories from South and Central America to East Africa hinge on regional specificity (Huehuetenango, Minas Gerais, Yirgacheffe), and there isn’t a reason Southeast Asia can’t participate in a similar manner.

Since Indonesia consists mostly of smallholder farms, change is bound to be gradual; but this isn’t stopping some producers from stepping up, changing quality, and differentiating themselves. With their continuing effort, we can expect to see more and more exciting coffees coming out of Indonesia.

Evan Gilman is an American coffee professional based in Indonesia. Read more Evan Gilman on Sprudge.