He didn’t always hear the cars coming, they sometimes surprised him, which he didn’t understand because every car made the same sounds. There was the distant whine of warm rubber on hot desert asphalt and the scream of the engine. Both sounds grew louder and deeper up to the pendulum point and then faded in the same way they arrived.

If they stopped, the engine would grunt, catching its breath, and the gravel would pop under the tires. Sometimes, hours passed, probably, and he didn’t even see a car on the road, let alone one pulling up to his tall windows, which sloped inward and announced, in hand-painted gold letters with white borders, that they had arrived at the Keep Driving Diner.

The people who took this road had their reasons. There were better ways to go, better roads and, of course, better destinations.

“Does Keep Driving Diner mean you think people should keep driving,” customers often asked, “or does it mean we don’t have any choice after we leave because it’s so far to another anything?”

“Yes,” he always answered.

His ambivalence was practiced and professional and fine armor. Nobody expected a five-star customer service experience here. If he was lucky, relatively speaking, a customer would notice the espresso machine, immaculate and impossible, just as shiny and clean as the first espresso machine he ever unpacked from a crate years ago, long before he had ever heard of anything like a barista competition, and long before he met The Coach. The people who saw the espresso machine acted like it was an oasis in this desert. Maybe it was. Those were the people he could tell the truth.

After a time, he gave up trying to understand why some cars stopped at the diner and some did not. Those who did stop didn’t all stop for the same reason. Nobody stopped because they were hungry.

There were no menus. Everyone received the same meal, two eggs over easy, two pieces of toast, two sausage links, a small glass of orange juice and a mug of coffee. The food was served almost as soon as they were seated and he would stand over them, waiting.

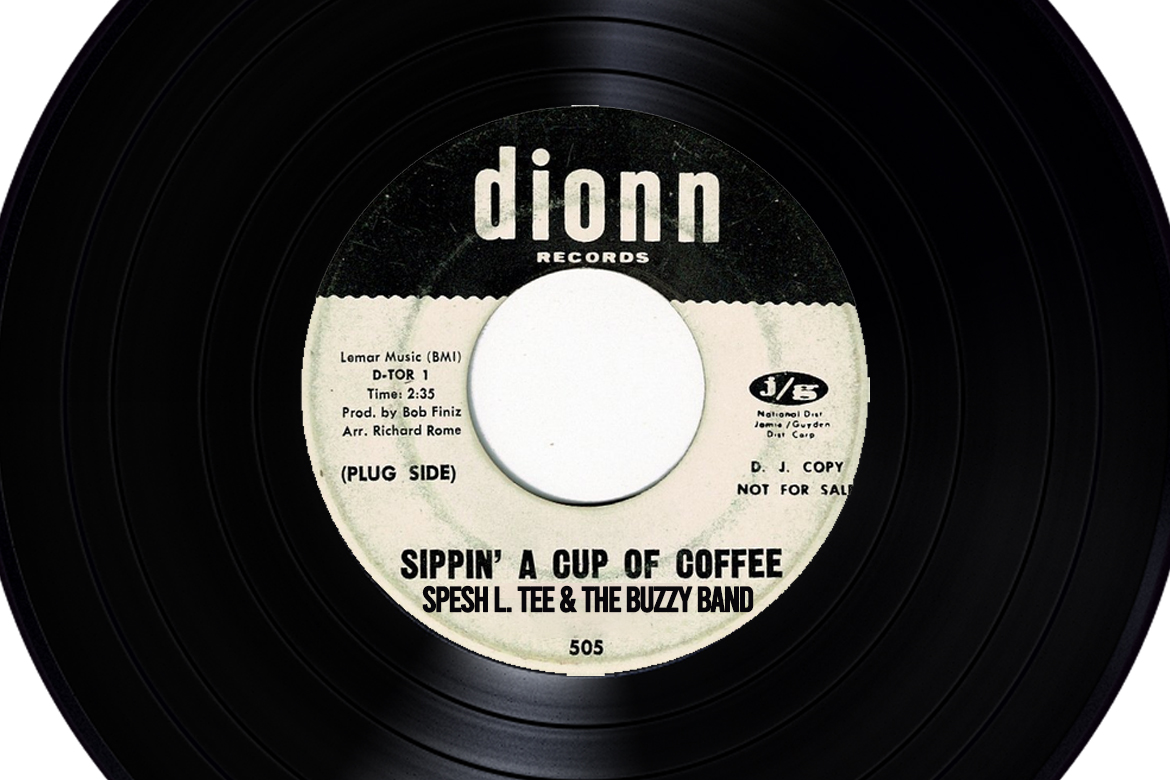

Some people didn’t take a drink of their coffee right away, but most people did and they all said something about how good it was, and then he would walk away, clinging to what scraps of gratification were still available to him.

His favorite responses were those he had not heard before, but those were very rare, very precious. Once, a woman said the coffee was flabbergasting, and he felt a little bit of the tickle in his bones he felt before this, when someone would finish a shot of espresso and then use their finger to clear what remained in the cup and lick it.

But most people just said something simple like, “That’s a good cup of coffee,” and he liked that too. He would take a seat on the stool at the end of the counter, in case they wanted to talk, and also to see if the espresso machine behind him caught their attention.

—-

Andrew Beckman, known as Beck to almost everyone except his parents, always hated all the cameras and microphones and the music and the giant screen. Most of all, he loathed his need to prove something, which made him endure the whole circus of it.

Beck cared about the coffee, the machine, his hands, and the person he was serving. In that order. Eventually, he came to believe that nobody in the world could possibly be better at it than he was. He understood that this belief represented a serious flaw in his character, but it was ingrained. It couldn’t be removed. That’s how he thought of it, not as arrogance, but as something inside him, like his liver or his lungs.

His father had barely contained his rage, his voice rising to a scream.

“You’re not going to law school because, wait, maybe I misheard you, you’ve decided to be a doctor? Or wait, maybe you said dentist or professor or banker or accountant. Maybe…maybe you said you’re going to be a fucking actor, but you sure as hell didn’t just tell me I sent you to college for five years so you could make goddamned coffee for a goddamned living goddamn it!”

“That about covers it,” said Beck, who wasn’t ever accused of being long on words. “I will pay you back for college.”

He could have done it too, but once his dad understood Beck was actually opening a coffeehouse, which he would own and operate, he calmed down. Then, when he saw how successful the business was, he would stop in with his golf buddies on Saturday mornings, because he was proud.

Beck was proud too. He was proud of the espresso he made. Cindy, his store manager, was really the one responsible for the success of the business. Beck gave her free reign over everything except the coffee.

After eight months, she said she needed to talk to him, so they went to Jakes, a small bar just a few doors down from the coffeehouse.

“We need to increase the number of hours we are open,” she said.

Beck nodded. He wasn’t sure how she figured this to be the case but she hadn’t been wrong about too much. He had met Cindy through her girlfriend, Helen, a college friend. When he told Helen about his plans, her eyes lit up and she told him he had to meet Cindy because she was going to be his coffeehouse manager. He did and she was.

“But Beck, if we are open more hours, we’ll need to hire some baristas. You won’t be able to pull almost every shot in the house, like you have been.”

He tensed. This had been the only real sticking point between them. Cindy had been a barista for years, but he insisted on retraining her, from scratch, for weeks, before he would allow her to relieve him on the bar.

“I promise,” said Cindy, “I will let you train them for as long as you want, but before long we will be open fifteen hours a day, maybe more some days. We’re a coffeehouse, we need baristas.”

He knew this conversation was coming eventually and he knew she was right, but it was going to be hard to see other people on the machine.

“Okay,” he said. “But I have demands too. The landlord tells me the florist next door is closing. He asked if we would be interested in the space. I want to expand and install a roaster and start roasting coffee.”

“Well, no surprise there,” said Cindy. “If you have to give up some control on the espresso machine, you’re going to take it back somewhere else and start roasting your own coffee.”

“That’s not all,” said Beck. “Starting now you are a full partner in the business.”

So began the rise of Lawless Coffee (named in honor of his decision not to go to law school) and his reputation as a barista. He’d been a barista all through college and was known among local baristas as being one of the best in the city. But as Lawless Coffee grew, his reputation grew and baristas actually made pilgrimages from all over to try his espresso.

The entire time he had to fight to stay behind the machine. There was constant pressure for him to do other things, but Cindy made sure he had as many shifts as possible. She said it was part of their brand, the owner who still pulled shots almost every day.

When he trained baristas, it was like boot camp and it was not unusual for a barista to quit during training. It was one of the baristas that made it through, Manny, who started pushing him to enter a barista competition. Beck dismissed the idea as ludicrous but it nagged at him.

Then one night, he found himself downloading the competition rules and a new obsession was born.

The first three times he competed he didn’t make the finals.

“It’s a performance, boss,” said Manny. “And it’s not a coffee competition, it’s a barista competition.”

“I’m not a performer, Manny.”

“Come on, that’s just not true. Are you telling me that when Mrs. Clay comes in here and you’re making her cappuccino and she is telling you for the umpteenth time about her poodle, Frank, and you smile and nod and ask questions, you’re not performing, just a little?”

“Maybe . . . a little.”

“Boss, you gotta get your obsession on, like you do with espresso and roasting.”

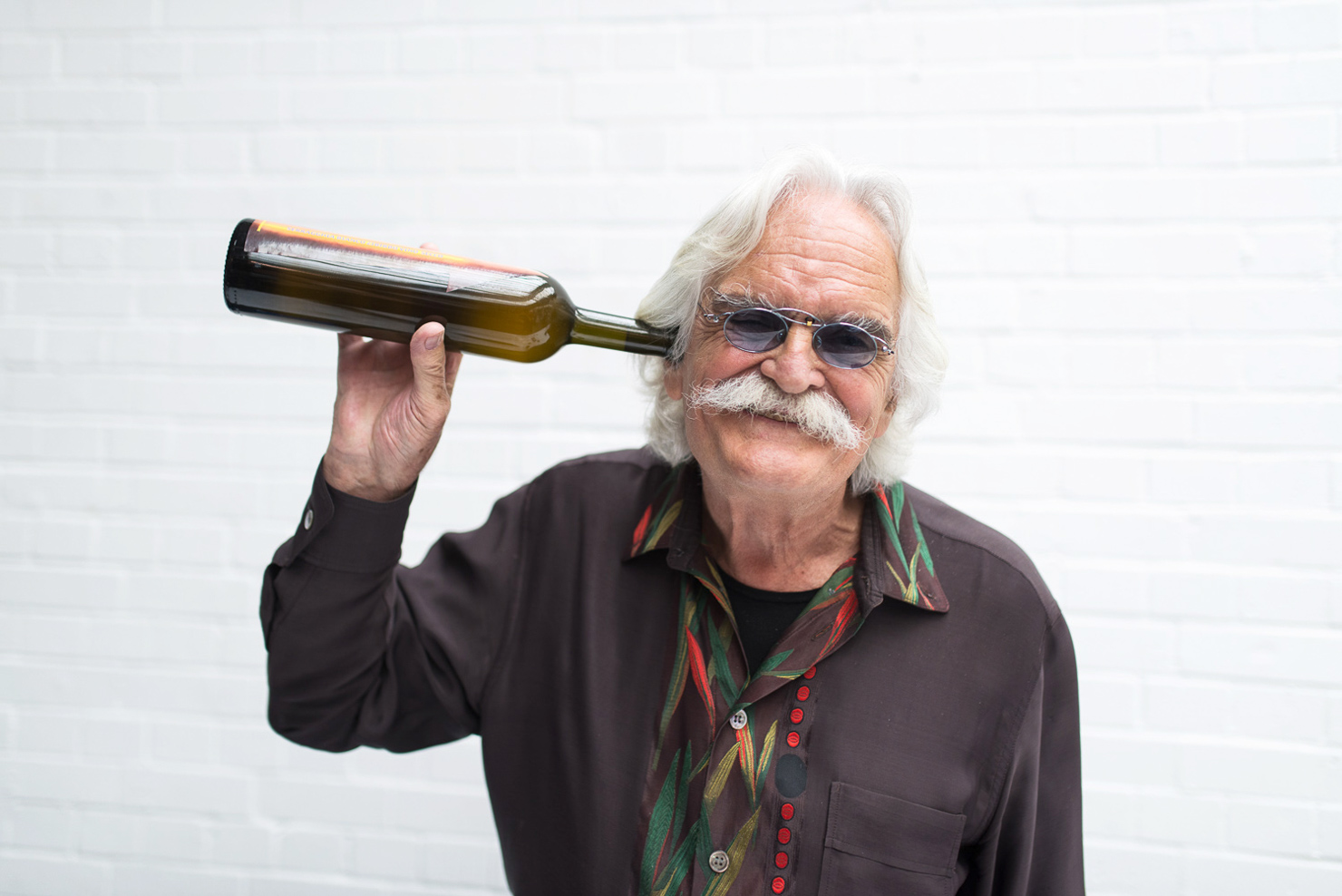

Beck did just that. He studied other successful competitors closely. He developed what he called his game face, a relaxed demeanor more consistent with his appearance, which a college girlfriend had described as “cowboy lank.” It wasn’t quite a persona. He was being himself, only more so. He began to place in the top six every time he competed and then winning his regional. Then he had a series of top three finishes at the nationals.

After his second year in a row placing second at the nationals, he started thinking he might pack it in. He’d been competing for eight years but had never won the nationals, so he could not compete in the world championships. Other competition baristas called him the old man and made half jokes about his retirement, but they also sought his advice.

Along with Cindy, he owned a successful coffee roasting and retailing company. They opened a roasting plant and there were now three Lawless coffeehouses and numerous wholesale accounts throughout the region. Maybe it was time he paid more attention to business.

But he couldn’t stop thinking about the world championships. The only way to compete against the best baristas in the world was to win the nationals, which he kept losing by small margins on points. He was thinking about these small margins when he met The Coach.

It was late and he was alone at the roastery, cupping coffee, and working on a new espresso blend when he was startled by a voice.

“So, you gonna give up then? Call it a day now? Retire those, whadda you call ‘em, portable filters and stuff?”

He looked over the rail of the mezzanine in the roastery where he sample roasted and cupped coffee. He expected to see one of the roasters or one of the production crew, someone playing a joke. Instead, he saw a heavyset middle-aged man wearing a black sweat suit, the designer type that no one ever actually wore for exercise.

“Who are you?” Beck said. “We’re not really open to the public right now, I mean, how did you get in here anyway?”

“Relax, Slinger. You don’t mind if I call you Slinger, do you? Anyway, the door was unlocked.”

“What do you want?” he asked, and he didn’t sound welcoming because the door was never unlocked.

“I just want to help you Slinger, got it, I’m The Coach, I got what you need to be the world’s best, you know, barista, whatever.”

Beck descended the metal stairs cautiously. “I don’t understand what you’re talking about.”

The Coach frowned. “Listen to me, Slinger. What’s your problem?”

“Hey, you barge in here, uninvited, I don’t know who you are . . . ”

“No, we’re not talking about me right now,” said The Coach. “We are talking about you and what’s your problem. Your problem is you can’t win. Why can’t you win?”

“I come close.”

“Horseshoes and hand grenades, kid. Why don’t you win?”

“I don’t know.”

The Coach raised his voice. “Why don’t you win?”

“Who are you?”

Then The Coach was screaming at him. “Why don’t you win, Slinger?”

Beck didn’t believe in life changing moments. He just didn’t. But he understood what The Coach was yelling about. He knew why he couldn’t win.

“It’s too much,” he said. “Too many distractions with the cameras and the bleachers and the microphones and all those people who are never going to taste my coffee just watching me, staring. It’s not real.”

“Alright, alright,” said The Coach, his voice soft. “I’m going to help you, I’m going to make it so you can win.”

Beck had never heard of betting on barista competitions, but that made the most sense as he looked at The Coach.

“I have to win honestly,” he said.

The Coach raised his hands up in surrender. “Hey, who said anything about cheating? I didn’t. It’s all on the up and up. I’m just going to make everything disappear in your mind except you, the machine, and the people you are giving the coffee to, those judges or whatever, help you focus, but the rest is up to you. You still gotta win it.”

“How can you do that?”

“It’s hard to say. It’s like hypnosis, maybe. But here’s the thing, Slinger, you gotta pay me back and probably with interest, if you know what I mean.”

“Pay you back? Pay you back how? You mean a fee?”

“Nothing like that. I mean you come work for me for a while.”

Beck looked over The Coach’s shoulder at the door to the roastery. The door to the roastery was never unlocked. Something was wrong.

“I don’t understand what this is about,” he said. “You have to tell me who you are.”

“I’m The Coach, Slinger. I make deals, I help people out, and they owe me a favor.”

Beck smirked. “You’re the Godfather?”

“Hey, I was around long before the movie. They ripped me off, you understand, not the other way around. But I know what you’re saying and, yeah, it’s like The Godfather. You come work for me.”

“You mean for eternity?”

“Oh, Jesus Christ,” said The Coach. “Here we go with the eternity thing. No, nothing like that. This isn’t a fairytale. Do you know how unsustainable eternity is?”

“How long then?”

“Hard to say, but not forever. I don’t make all the rules. Until your replacement shows up.”

“When . . . when do I go to work for you?”

“The first time you lose, Slinger.”

“What if I just keep winning?”

“Nobody just keeps winning, nobody never. Remember, I’m just healing a weakness. You still have to do all the things you do now to win.”

“What if I lose my first time out?”

“The deal doesn’t go into effect until you win, only then do you have to keep winning.”

Beck understood it was a bad idea. He didn’t try and lie to himself about it. He just repeated to himself over and over, “The best barista in the world,” and extended his hand.

But Slinger didn’t lose after shaking hands with The Coach. He won his regional. He won nationals. He won the World Championship, not once, but five times. He became a legend.

When he finally lost, it wasn’t competing against the best baristas in the world, or even the best in the country. He lost through simple inattention and he wasn’t even on a competition stage when it happened. There were no cameras or microphones or internet broadcasts.

He was coaxed into entering a latte art competition hosted by Lawless Coffee at their downtown location. He did well, made it to the final pour, and never once did it occur to him that the stakes were greater than the entry fee purse, which he would have donated anyway.

One moment the judges were pointing at his competitor’s cup, a barista who worked for him, and he was laughing and listening to the roar and applause of the dozens of people watching. The next moment he was listening to the whine of warm rubber on hot desert asphalt and the scream of a car engine.

—-

The car that pulled up to the Keep Driving Diner moments after Slinger arrived, while he was still disoriented and feeling sick to his stomach, was the same car that would always pull up, or drive by, a dark blue 1953 Buick Skylark. He knew the car because his grandfather had owned one. Recognizing the car helped him focus. When The Coach got out of the car, all the fuzziness went away.

As the diner door opened, The Coach was already talking.

“First day of work, I know, it’s always a little disorienting,” he said.

Slinger looked around, noticed the espresso machine, the same machine he installed at Lawless when they first opened.

“Where are we?”

“Hard to say,” said The Coach. “Probably somewhere near the middle. Probably the exact middle if I hadda guess.”

“The middle?”

“Yeah, look, Slinger, I know it’s a lot to take in and all, but the pieces of the puzzle, well, most of them anyway, come together pretty quickly. I mean, the orientation is automatic, you just need to let it happen, okay.”

Slinger walked behind the long service counter and stood at the espresso machine because it was the only thing that made sense to him. It wasn’t the same model he had originally installed at Lawless, he felt certain it was the exact same machine. Then he remembered the latte art competition.

“Small print I guess,” he said.

“Whoa, whoa, whoa,” said The Coach, “I was very clear, when you lose, you come work for me.”

“But we were talking about barista competitions.”

“You know, Slinger, I don’t remember that stipulation. What I remember is, you compete and you lose, you’re mine. You want to look at a transcript? I don’t want no disgruntled worker here.”

But Slinger already knew The Coach was right. And it didn’t matter. Here he was.

“Look,” said The Coach, “it’s not a bad gig. You work the diner. People stop, they eat, they drink your coffee, and maybe they even have an espresso, if you can imagine that. It’s not a bad job.”

“But what am I supposed to accomplish, why am I here?”

“I know, I know, you’re still thinking like before, but it’ll pass. You work the diner, that’s all. You never get tired, you never get hungry, you never even get bored or lonely, and you never get horny. You can’t even go insane. I mean, it could be worse, believe me.”

Slinger took in the rest of the diner, four booths and three tables. Four counter stools. Even as questions came to his mind, they were answered, except for the question why. All the operation details of the diner appeared, like auto-fill, in his mind. Mostly, everything would just happen, except the coffee, which he actually had to brew. There was a reason for this, but it wasn’t given to him and he knew it never would be. This fact became less and less important to him with each passing moment.

“I’m forgetting the before,” he said.

“No you’re not,” said The Coach. “Your mind is just setting priorities, adjusting. You can call back things from before if you need them.”

“Will I need them?”

“No, not really.”

Because he had nothing else to do, he started the grinder and pulled two shots of espresso and placed one on the counter for The Coach. He looked outside at the car.

“What’s with the car?” he asked.

“That’s the car I was driving, you know, in the world, when I was hired?” said The Coach.

“Hired? You’re not the boss?”

The Coach laughed. “No, Slinger, the boss doesn’t do grunt work. This is grunt work, what I do, and you, you’re a temp worker. I’m not the boss, I’m just an employee.”

The Coach drank his espresso and Slinger followed.

“That’s a damn fine espresso,” said The Coach. “And I know espresso, let me tell you.”

Slinger accepted the compliment but knew that The Coach did not, truly, know espresso. He pulled the lid off the grinder and smelled the coffee. It was his own espresso blend, he could tell. He knew that the grinder would always be full and the coffee would always be fresh.

“What do I do?” he asked.

“You’ll know what to do,” said The Coach. “Look, Slinger, I won’t see you again. This isn’t a good and evil thing, okay. It’s just an equation. Like you, I’m just part of the formula. I’m telling you this now while it still means something to you. Soon, you’ll be…well, in your groove and you won’t worry. But there might be times when you think of the before, when someone comes in to the diner and reminds you of something you thought you had forgotten. Slinger, I’m an employee, you’re just a temp worker. Remember that, kid. You best brew up a pot now.”

The Coach left. Slinger tried to walk him to his car but he couldn’t leave the diner. He just paused in the doorway, as if he were waiting for something that never happened.

And then Buicks began to drive past. Then one stopped. Slinger found a plate of eggs, toast and sausages in one hand and orange juice in the other. He served the customers, the customers ate. They said the coffee was good. They left. Nobody talked to him much at first.

Finally, it may have been his fifth customer or his fiftieth customer, someone noticed the espresso machine and asked for a cappuccino.

The customer was an elderly man who did not remove his raincoat.

He sipped his cappuccino several times and looked at Slinger, who was already in the habit of sitting on the last counter stool.

“You are kidding me with this, right?” said the customer.

Somehow, Slinger knew what the man meant, and he said, “It’s not fair is it?”

The man wiped his mouth with his napkin and then threw the napkin onto his plate.

“You’re damn fucking straight it’s not fair, you little shit. I drink coffee my whole life, since I am five years old, and it’s not until I’m on the road to Hell that I taste the best cappuccino of my life?”

That was when Slinger realized that the people who could see the espresso machine were the people who understood where they were and some of them wanted to talk.

After drinking their espresso or sipping their cappuccino, they would say something like, “I’m not sure where I am.”

“I know. It’s okay, just keep driving,” he would say.

“I don’t think this ends well,” some of them would add.

“It ends as well as it can but not as bad as you imagine. Just keep driving.”

He did his job. Some people were clueless. They ate because there was food. They stopped because there was a diner. They kept driving because there was a road. Others had inklings and it was his job to keep them moving. His coffee helped them face the road ahead. Hadn’t it always been so?

Then, after many people had tasted his espresso and many many more had never even noticed the machine, a third sort of person entered the diner.

A young man, under twenty-five for certain, walked into the diner and took a seat at the counter. It was the first time that had happened. Slinger delivered a plate of food, but the man ignored it.

“You Beck?” the man asked.

Hearing his name disoriented him for a moment.

“Yes,” he said.

“I’m Tommy. I hear you’re the best there ever was.”

“Who told you that?”

“I don’t know. He calls himself The Professor.”

Slinger laughed at this. “Okay, so what do you want?”

“Bullet for bullet,” Tommy said. “One shot each.”

Slinger bowed slightly and invited him behind the counter. This was something new, something that tingled his bones. Although he never felt unhappy in the diner, exactly, he now felt something more than what he usually felt, something extra.

They each pulled and exchanged a shot of espresso, and then traded again, so they were tasting their own shots second.

There were no lies in the diner, no hubris or self-delusion, aside from the fact that some customers did not know they were dead. So when espresso shots were exchanged, there was no question, no debate, and no appeal. Slinger won.

Tommy left the diner and for the first time Slinger watched a car turn left onto the highway and go back from where it came. Tommy was returning to life and whatever arrangement The Coach, or, The Professor, had manipulated.

After that, people like Tommy started arriving, if not often, regularly. They always sat at the counter and did not take their eyes of the espresso machine. These people were not dead and they all knew his name. Slowly, it dawned on him that The Coach was using him as bait. So he understood a little of his purpose.

It always went down the same way. Sometimes, no words were spoken after they asked if he was Beck. They pulled their shots, tasted the espresso, and lost their bet, or whatever, with The Coach, then left. Nobody complained. Nobody protested. Nobody tried to adjust the grind.

He wondered, in the beginning, if he could sandbag, try and lose intentionally, to see what would happen. But he could not do less than his best any more than he could leave the diner.

Everyone, living or dead, arrived and departed in the Buick, including the last person, Erica.

She arrived in one of the cars that he did not hear until it was in front of the diner. She didn’t look at him when she entered, she just looked at the espresso machine and took a seat at the counter. That wasn’t unusual. What was unusual was that she didn’t say anything. The challengers all spoke first, asking if he was Beck, or saying they were looking for Beck.

He waited, and when it looked like she might decide to just stare at the espresso machine forever, he asked, “Can I help you?”

She acted as if she had not noticed he was standing there until he spoke.

“I’m not sure,” she said. “Where am I?”

“The Keep Driving Diner,” he said, “or The Middle. Are you looking for Beck?”

“I’m looking for a job.”

“Oh? Who sent you here?”

“The Investor. My name is Erica. I believe I am expected.”

“I see,” said Slinger. “What sort of job are you looking for?”

“The best barista who ever lived,” she said, and her eyes drifted back to the espresso machine.

Her long brown hair, her plaid shirt, reminded him if Cindy, and he realized he had not thought of Cindy in a very long time, but he didn’t know if this meant days or years. This was followed by a feeling he had not experienced since…since before. He felt guilty for making Cindy shoulder most of the burden for running their business. This was followed by remembering his father, who went far beyond being proud of him. His father became the number one cheerleader for Lawless Coffee. After he retired, his father would come to the roastery and start sweeping.

“Dad,” Beck would plead, “you don’t need to do that.” But his Dad would just smile and keep sweeping. Slinger felt like it had been a very long time since he had memories like this, memories of before. But how would he know?

He stepped back and bowed slightly, as was his way, inviting Erica behind the counter. “Well, best barista that ever lived is quite the job title,” he said. “Let’s see what you’ve got.”

They pulled their shots and Slinger found something about Erica familiar. He wondered if they had ever met. Maybe what was familiar was how she looked standing at the espresso machine, like she had always been there.

He lifted her shot to his lips and paused. He stared at the espresso in the demitasse cup. It seemed familiar to him, the same way that Erica looked familiar while she was pulling the shot. Then he understood that she looked familiar because she moved like he moved.

As her espresso spread over his tongue, he closed his eyes and he knew he had just lost.

When he opened his eyes, Erica had just finished tasting his espresso and there was no question on her face. She knew she had won.

He looked outside at the dark blue Buick Skylark parked in front of the diner.

“You’re hired, Slinger,” he said. He took off his apron as he rounded the counter, heading for the door.

“My name is Erica,” she said, and she was smug in a way that he did not consider unappealing.

“No, it’s not,” he said. “The Investor will be along shortly. He’ll explain.”

He opened the diner door and stepped out into the desert heat. The Buick’s interior was like an oven and he had memories of riding with his grandfather. He started the car, backed up slowly, listening with pleasure to the sound of the pebbles crunching under the tires. He turned the car around and rolled the window down as he idled toward the highway. When the tires hit the asphalt, he turned on the left-hand turn signal.

This has been Weekend Sprudge Reader. Your feedback is welcome.

Mike Ferguson is an American coffee professional and writer based in Atlanta. Read more Mike Ferguson on Sprudge.