“Untact” is a big keyword in South Korea right now, where life seems to be almost back to normal. You didn’t read it wrong; “Untact” is not even an entirely new word. It was coined by consumer studies researchers in South Korea in 2017 to mean the negation of contact in an increasingly virtual world, including contactless payments, self-service kiosks, and even “smart mirrors” making custom pigment recommendations for beauty shoppers. At its core, “untact” speaks to the mechanism of reducing direct human contact facilitated by digital interfaces, which has implications beyond retail and commerce.

From early on in the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic the South Korean government instituted strict testing and tracing measures facilitated by nationwide tech and data infrastructure. This was building on what the country had learned through everything they had done wrong during the two-month outbreak of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015. South Korea’s aggressive tracing of COVID-19 allowed for infected persons’ exact routes minute by minute to be tracked and made available to the public. The country could avoid imposing shelter-in-place or the temporary closure of non-essential businesses, as was the case in many countries including in China, Italy, and the U.S.

Still, the hyper tracing of infected patients and the dissemination of this information to the public instilled fear in cafe owners and operators. Closing the business was out of the question for many because that meant forgoing sales. Their fear was reinforced by neighboring cafes and other small businesses that had to close down following location tracking of identified infected patients that had passed through their doors.

Kyungmi Kim is owner of Elarca cafe in Daegu, the fourth biggest city in Korea, which in February of 2020 had the largest number of infections in the world outside of China. Daegu’s city government was quick to respond via real-time alerts notifying the routes of infected patients. Kim recounts her anxiety monitoring the COVID-19 tracker app: “I was constantly anxious in the off-chance that an infected person may have passed through my cafe.” Kim quickly decreased operating hours, religiously disinfected surfaces in her shop, and started offering deliveries. Fear was a common word used to describe the tracing and tracking mechanism for cafe owners and operators in Daegu.

Fast forward a few months, where do cafes stand in South Korea’s capital Seoul? I spoke to a range of individuals, including cafe-goers and cafe owners, to understand more about what the scene is like right now. The truth is, while overall Seoul’s response to COVID-19 has been effective, the pandemic is not over. Certain areas in Seoul are having a hard time following news of mass contagion. “When a confirmed patient is traced back to a specific business joint, everyone starts to associate the place with COVID and actively avoids going there,” cafe-goer Kelly Shin explains. Some cafes have closed down temporarily since news of such incidents. This is especially true of the Itaewon district, which is known to be a local hangout spot for food and drinks and less populated by commercial offices.

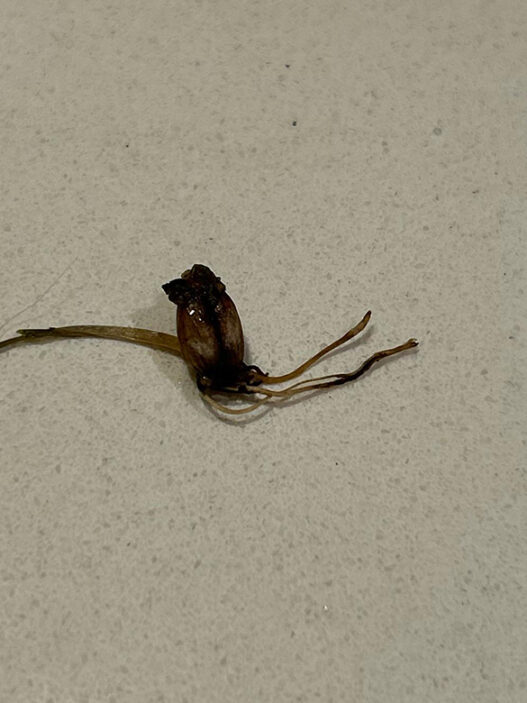

Newly opened cafes that were just starting to get their name out pre-COVID are struggling. Affair Coffee is a couple-run micro-roastery and cafe that opened on January 1st 2020. Just as Affair started getting a steady stream of customers, COVID hit. “Sight of the ambulance and medical staff fully dressed in protective gear in the neighborhood became common,” explains co-owner Hyunsun Park. Located near the Han River, a popular outdoor activity area, Affair could easily attract customers to grab and go coffee en route to the day’s activities. But Park found herself in a moral dilemma. How should she continue to promote her new micro-roastery cafe and survive through the pandemic while at the same time be socially responsible? “Posting anything on Instagram required painstaking thinking and reasoning. I didn’t want to encourage any unnecessary socializing by promoting Affair as a takeout spot,” Park explains.

More established brands like Bean Brothers, a coffee company with seven locations, experienced varying degrees of COVID-19 impact across its shops. “Our shops inside shopping malls suffered the most,” says Bean Brothers’ Marketing Manager Seo Young Youn, “while the more spacious shops with plenty of space between seating suffered the least.”

Bean Brothers had a confirmed patient in one of its locations early May. Government representatives reached out to trace the exact route of the infected patient within the shop. The officials, together with management, confirmed that the patient was not wearing a mask. Baristas from that shift immediately got tested and followed through with established protocol. For many weeks following, Bean Brothers posted a sign at the entrance notifying customers of this incident. “At first customers would turn away after seeing the note at the door,” says Head Barista Jae Yoon Kim, “but soon it didn’t seem to matter as much.” Rather, some customers started to trust Bean Brothers more for having taken full control over the situation, according to Kim. Some thought the location was safer following the incident than before, since it was disinfected thoroughly.

Now business is back to normal for Bean Brothers at this location and its six other locations. Jae Yoon Kim says with a smile, “We’re back to normal life I guess except now everyone has a mask on,” says Jae Yoon Kim. If not back to pre-COVID sales figures, they’re at least close.

Co-founder BK Kim of Fritz Coffee Company, a coffee roaster and bakery now with three locations in Seoul (and a growing American following thanks to appearances at LA’s Dayglow Coffee), explains that since the government enforced strict contact tracing and figures dipped to below 100 new cases a day, business quickly came back to normal. Fritz has not seen a dip in customer count. “Everything is how things used to be, except we are wearing masks wherever we go,” BK Kim says. The ratio between in-store and take-out customers remains largely unchanged. Still, BK Kim is thinking about what an untact world looks like for Fritz beyond COVID. The brand is well-known for its direct trade model with producers at origin. When asked about how the travel restrictions would impact this model, BK Kim explained that Fritz had already established lasting relationships with producers with whom they communicate regularly through digital messenger services like WhatsApp.

Things are even more favorable for Jung Yi Jung, a neighborhood cafe that also serves as an art and community space, in recent weeks has seen a surge in sales of up to 150% since COVID. “We had one confirmed infected patient in Jongam, the neighborhood my cafe is in,” says cafe co-owner Myungbae Lee. “I was afraid that this person may have passed through Jung Yi Jung, and was nervous until the person’s exact route was publicly announced.” Lee noticed that college students take online courses in the convenience of cafes in their neighborhood. Jung Yi Jung initially checked temperature at entrance but stopped after some customers expressed discomfort.

Compared to the U.S., the Korean government has not provided significant financial assistance or subsidies to small businesses (like the Small Business Association’s Payment Protection Program or the Economic Injury Disaster Loans). But from conversations with cafe owners and operators, it seemed that more than direct financial assistance, they wish for strict enforcement of fines on citizens not wearing masks or breaking self-isolation protocol. Some want more government intervention and legal enforcement for cafe operators and baristas to be able to protect themselves from customers.

The U.S. today is far from being able to imagine what a post-COVID world might look like. But if we were to ask: what happens in a world of “social prevention” (a phrase coined by the Korean government), beyond social distancing? South Korea is an exemplary case demonstrating the power of government intervention in disease management. The health of the cafe industry and small businesses in Korea is closely tied to the government’s ability to contain and manage the virus from early on. And while the geographic and population scales of the two countries are very different, Korea offers a poignant comparison to the U.S. coronavirus response. By resorting to total lockdowns in certain states, with the looming threat of more if reopening goes poorly, small businesses in the United States are facing down a kind of economic paralysis, with much uncertainty for the future. Meanwhile the Korean government, by instituting aggressive testing and tracing from the beginning, has made it possible for local economies to stay afloat while avoiding economic lockdown.

Indeed things have normalized in South Korea, with newly confirmed cases of COVID stabilized, and many people are back to living something like normal lives, albeit one in which citizens use an app to report anyone who is not wearing a mask on the subway in real time. Untact is now part of this new normal, and that isn’t changing anytime soon. This new word is now more than an adjective; it reflects the collective mentality and psyche of South Koreans in 2020. Need more proof? Go type “untact”—”언택트”—into the search box on South Korea’s leading search engine, Naver, and here is what you’ll get in autosuggest: untact era, untact travel, untact marketing, untact stocks, untact business, untact fan meeting, and the list goes on. We’re living in the untact era, and coffee is along for the ride.

Jiyoon Han is a Q Grader and coffee professional based in New York City and Boston. She is Co-Founder of the Coffee & Tea Club at Harvard Business School. This is Jiyoon Han’s first feature for Sprudge.

Top photo by Hyunsun Park.