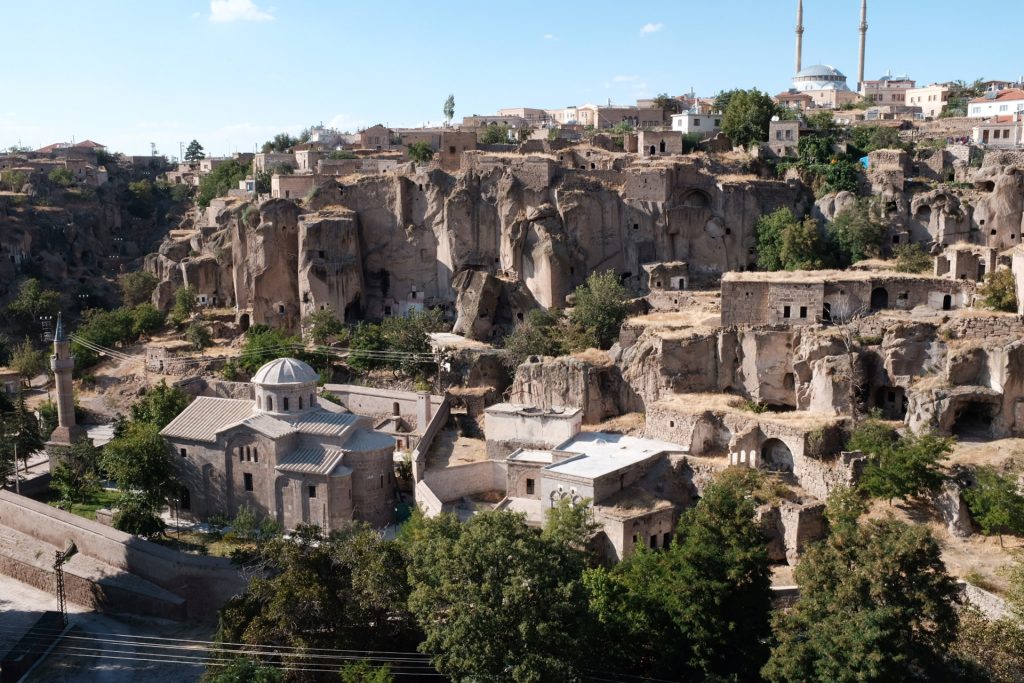

Driving across Kapadokya in rural Anatolia, one feels they’ve been transported to an alien landscape. As an Arizona native, I find uncanny parallels to the American Southwest: the dramatic rock formations, the harsh, barren landscape. Country roads, only sometimes paved, weave between crumbling stone houses. An occasional shepherd stops to stare at my polished rental car, which leaves a cloud of white dust in its wake. Having just arrived from dense, urban Istanbul, I feel overwhelmed by both the region’s beauty and melancholy, reflected in the weather-worn faces of those I pass.

In Byzantine times, local inhabitants carved houses and churches out of the soft volcanic rock—in the side of cliffs, at the top of mountains, even underground cave villages that extend deep into the earth in a series of narrow, claustrophobia-inducing tunnels. History, perhaps, best knows the region as home to theologians Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil of Caesarea, who shaped Nicean Christianity with their books and creeds. More recently, Kapadokya is better known as the hot air balloon capital of the world, and anyone with an Instagram account has likely seen a picture of its panorama, the chalky landscape littered with floating, fluorescent balloons.

It’s my second visit to Kapadokya, and this time around I’m not here to see any of the sights. I’ve come to visit a pair of winemakers trying to revive an ancient tradition in a small village called Güzelyurt, Turkish for “beautiful land.” Turkey, after all, is home to over 800 indigenous varieties of grapes, and people have been making wine here since at least the post-neolithic period. But the ancient winemaking traditions of Anatolia experienced a massive shift in the 20th century, which saw a state monopoly on alcohol production that legally encoded industrial winemaking methods, manufactured by a couple of large-scale factories. But a rather unlikely couple, a German wildlife conservationist-turned winemaker named Udo Hirsch and his Turkish partner, Hacer Özkaya, are trying to rediscover the old ways. Hirsch and Özkaya make wine under the name of Gelveri Manufactur with almost no modern equipment, preferring to use antique küp, or amphora, to ferment and age their wine.

Hirsch and Özkaya meet me outside the village mosque and we walk to their nearby house, lovingly dubbed “the Taş Mahal” (“taş” is Turkish for “stone”). Hirsch is tall and lanky, with a tangled mess of cowlicky white hair. At 75 years old, he exudes a surprising athleticism, perhaps seen most clearly as he punches down the freshly fermenting wine with a large wooden stick—a task that must be repeated every two hours, day and night, the first week of fermentation. Later, in the cellar, I struggle to keep up with him as he descends the steep, uneven stairs with agility—pausing only to warn me of a sudden drop or low-hanging doorway. Özkaya is calm and welcoming, with kind eyes and striking streaks of silver in her dark hair. Save for her penchant for technical outdoorswear, she’s the picture of a Turkish hostess—constantly working behind the scenes to prepare food and drink. Özkaya, like Hirsch, has varied interests. She keeps a garden and teaches ceramics classes to local university students.

I’ve arrived just in time for breakfast and am treated to an impressive spread: tomatoes and peppers from their garden, olives they picked from a friend’s farm and cured themselves, four types of homemade cheese, aged in their wine cellar, homemade yoghurt and pekmez, a molasses made from grapes from their vineyard.

As we drink black Turkish tea out of tulip-shaped glasses—I lose track of how many times my glass is refilled—Hirsch explains how they started to make wine.

“I wanted a quiet place to write my books,” he says. Having worked in Turkey off and on since 1969, Hirsch bought the house in the 1990s as a vacation home. His published works include a four-volume archeological study on the mother goddess of ancient Anatolian religions, as well as the official catalogue of the Vakıflar Carpet and Kilim Museum in Istanbul, a collection he helped curate between projects for the World Wildlife Foundation.

The winemaking was serendipitous.

Hirsch’s home is what locals call a “Greek house,” over 250 years old and quite literally carved from the rock. As Hirsch explains, the name is a bit of a misnomer, because even though the original owners were Eastern Orthodox Christians, ethnically they weren’t Greek. The house, like most old houses in the area, is equipped with a wine cellar. A hole carved in the ceiling allowed grapes to be dropped into a bathtub-like enclosure, where they were trod upon by foot. From there the juice drained down a small channel where it was collected in large amphora to undergo fermentation.

Gelveri, like many businesses and hotels in Güzelyurt, is named for the Greek name of the village. The name, like the inhabitants here, changed dramatically in 1924 when the newly formed nation-state of Turkey, following a bitter war with Greece, underwent a population swap in which millions of Christians living in Turkey were forced to move to Greece, and over a million Muslims living in the Balkans were forced to move to Turkey. The forcibly resettled migrants were given the abandoned homes of the former inhabitants. Churches were converted into mosques, (one mosque in Güzelyurt is officially named “the Church Mosque”) and the wine cellars were used for other purposes.

That was, until Hirsch bought one of the houses.

“I thought to myself, ‘Okay, I’ll make some wine for myself and my friends, because everything is there,’” says Hirsch. He then laughs. “My first wine, unfortunately, I had to drink myself. It was too bad.”

But for Hirsch, the seed had already been planted.

“I’m coming from Germany from a wine area, north of Mosel,” says Hirsch. “I know how people there make their wine, but I wasn’t doing it. I was mostly drinking it.”

That changed while working on a project for the World Wildlife Fund in Georgia. Most of Hirsch’s friends in Georgia made their own wine, using traditional methods in large amphora called qvevri.

“Traveling in the country I got very horrible wine and very good wine,” says Hirsch. This inspired Hirsch to explore what was possible using only traditional methods.

“I have never been trained in winemaking. I’m a nature conservationist. I came from there. I look from there,” he says. “Let’s make it natural. Let’s have a high biodiversity if possible. No impact if it’s not urgently needed. Leave it and let it go.”

Hirsch and Özkaya tried using the original stone tank a few times, but now opt to lightly crush each grape with a rubber roller before the whole clusters, stems and all, go into the amphora. Some cuvées might only see 50-70% whole cluster. “We have to find the balance for each grape,” says Hirsch. “And we’re still doing that.”

Gelveri only does single-varietal cuvées, a decision based on ignorance more than principal. “Our biggest problem is we don’t know enough about our grapes,” says Hirsch. “We are working with completely unknown grapes. They exist for maybe 10 km around, that’s it.”

Once in the amphora, the grapes undergo spontaneous fermentation with their native yeasts—sometimes starting the same day. White and reds alike are left to ferment for six months, before being pumped into secondary vessels to age for another six months before bottling. Although Gelveri used to add a small amount of sulfite at bottling, for three years now they’ve been “zero, zero”—no sulphur in the vineyard or bottling.

“We leave it as it is. This is the grape. This is its taste. This is the terroir,” says Hirsch.

Each küp is a regionally sourced antique, most of them hundreds of years old and some much older. When Hirsch was working with handwoven textiles, he developed a network of antique dealers, now tasked with finding the ancient küp rather than rugs and kilims. The largest of the collection, an Armenian vessel sourced in Tokat, is used for Gelveri’s red cuvée, Kalecik Karası. Weighing over a ton, the amphora is so large a garden wall had to be torn down when it was transported to Güzelyurt.

What started as a hobby quickly grew. Turkish law allows for individuals to home brew up to 350 liters of beer and wine for personal use without a permit, but more than that requires starting a firm. So while Hirsch focused on the winemaking, Özkaya began navigating the complex bureaucracy of setting up a winery in Turkey. In all, 13 different government agencies have to sign off, and inspections are frequent.

One of the many obstacles to overcome was receiving permission to ferment the wine in amphora. Inspectors were worried the porous material was a health hazard. As a compromise, Hirsch and Özkaya bought two stainless steel fermentation tanks— which are only occasionally used to briefly hold the wine when transferring it between the fermentation küp and and the aging küp.

Özkaya downplays the red tape. “It’s no problem,” she says. But Hirsch, tells a different story. “There’s no way I could do this without her,” he says.

The legal challenges, perhaps, point to the complicated topic of alcohol in Turkey. Under the Ottoman Empire, Christian and Jewish citizens were free to make and consume wine, which records show contributed significant tax revenue. But Muslims citizens were barred from drinking (though many did so in secret).

But the founding of the nation-state of Turkey in 1923 also saw alcohol laws lifted. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey’s founder, was himself an avid drinker of rakı, an anise-flavored brandy considered Turkey’s national drink. In many ways, Turkey has quite liberal alcohol laws. The drinking age is 18 and drinking in public parks is permitted, though frowned upon during Ramadan. But this liberal attitude towards alcohol has shifted in recent years as the ruling party has instituted new legal controls. Alcohol taxes were hiked an additional 15.5 in 2018 and alcohol companies are barred from doing any advertising, public tastings, or even using social media.

Güzelyurt, like most villages in Turkey, is conservative and some of Hirsch and Özkaya’s neighbors are scandalized by having a boutique winery in town.

“Sometimes we have a discussion in the market. We have a tea or something. They say ‘This is sin. It’s not so good,’” says Hirsch. “I say, ‘I don’t know what you want. We just pick the grapes and squeeze them, the rest is done by Allah. After that we bottle them and you come to drink them!’” The anecdote points to the reality that locals who imbibe, do so in private. “The tourists come during the day,” he says. “The Turks come after it’s become dark.”

But in Istanbul, Gelveri has a cult following, and those lucky enough to drink their wine don’t do so in secret, but brag on their Instagram accounts. Because it’s illegal to mail alcohol in Turkey, sommeliers from high end restaurants like Mikla and Neolokal make the seven hour drive to fill up a van.

The success for Gelveri at home followed some unexpected recognition abroad. First, one of their wines showed up unexpectedly on Noma’s wine list during their 2015 Tokyo pop-up (Danish chef Rene Redzepi has long been an advocate for natural wines.) Later that year Jordi Roca, of famed Catalonian restaurant El Cellar de Can Roca, selected their Hasan Dede to pair with a seafood dish during the Roca brothers’ guest stint in Istanbul. Attention from two restaurants atop the World’s Best list generated a lot of buzz—the kind of attention that it isn’t even legal to buy in Turkey.

Though demand is high, Hirsch has no interest in increasing production. “We are producing 5,000 bottles, and that’s it. We don’t want to make more because we want to enjoy it,” he says.

At Hirsch and Özkaya’s dining room table, we sit down to taste six of Gelveri’s cuvées. Özkaya brings a ceramic spittoon.

“In case you don’t like to drink wine,” says Hirsch. Hirsch and Özkaya don’t spit out the wine, so I don’t either.

We start with Keten Gömlek, literally “linen shirt” in Turkish, so named because the grape is so thin-skinned you can see the pips in the sunlight. The wine is a golden yellow, almost lager-like, with yeast and sediment visibly swirling in the bottle. In the glass, the nose offers aromas of candied hazelnuts and ripe stonefruit. Those nutty, oxidative qualities I associate with vin jaune from the Jura region continue on the palate, but open up to notes of dried apricot. This wine is vibrant, alive.

We move on to the deep and brooding Hasan Dede, a so-called orange wine. (Here, the name only alludes to the color imparted by the skins, as the vinification of the wines are the same). It opens with aromas of honey and orange peel. A burst of lychee and bergamot immediately give way to slowly building tannins, that linger on the tongue like oversteeped oolong tea. It’s complex, structured, and intense—the sort of wine that needs a food pairing to smooth it’s rougher edges. A natural wine for peated Scotch drinkers; decidedly not glou glou.

Next, we move on to the reds, Kalecik Karası, 2015 and 2016. This is the lone grape Gelveri works with that I was already familiar with. Known for its big fruit, high acidity, and low tannin, it’s a versatile grape grown in practically every wine producing region in Turkey. But the commercial versions are clones grown on American rootstocks. Here in Kapadokya, Gelveri has endemic, phylloxera-free vines growing on their original rootstocks, which Hirsch believes explains why his Kalecik Karası bears little resemblance to mass-produced versions.

İn the glass, the two vintages are starkly different. Clocking in at 14.5% alcohol, the 2015 is wild and austere. It shows some signs of volatile acidity, which fade after it’s been decanted for an hour. It has that elusive smoky taste I associate with amphora wines, be they Georgian or Sicilian. Hirsch only sees its potential. “This one needs another five, six years in the bottle,” he says. By contrast, the 2016 is youthful and juicy and only 13% alcohol. It reminds me of a Fluerie or Morgon, with its quaffable red fruit supported by an elegant, but firm structure.

An interesting cuvée that technically doesn’t meet the natural wine standard “nothing added, nothing taken away” is the Mayoğlu Terebinthe. Perhaps best understood as the Central Anatolian answer to retsina, the pine-resin flavored wine notorious in Greece, this century-old recipe comes from the original owners of Hirsch’s house: the Mayoğlu family, a family of jewelers that also distilled their own brandy they sold in Istanbul before being relocated in the population exchange. The cuvée calls for the best of the white grape harvest, which is macerated with a small amount of terebinth—a dried fruit known as menegiç in Turkish—which Gelveri sources from Özkaya’s hometown of Alanya on the Mediterranean coast. The fermentation takes a staggering two years, so the cuvée is only released biennially. It’s light and delicate, with wonderful florals. The terebinth notes take a subtle, supporting role, an extra touch of complexity in a fascinating yet refreshing wine.

The next morning I climb into the backseat of Hirsch’s station wagon and the three of us set off for their vineyard sites, about 20 minutes away in the foothills of Hasandağı, the towering, inactive volcano that fills the horizon. (Neolithic cave paintings—an area of interest for Hirsch—depict the volcano erupting.) Hirsch drives the mountain passes furiously, shifting into a passing gear even on blind turns to get around the occasional tractor, slowing only to pass the occasional villager riding a donkey (as we gain elevation, donkeys soon outnumber cars as the primary form of transportation.) At over 1500 MASL, we’re at the upper limits of where it’s possible to grow grapes. As we tread the sand-like tuff soil, I’m amazed any produce can be coaxed from this harsh land.

To those familiar with the neat, orderly rows of a vineyard with vines growing on trellises, the chaos of Gelveri’s vineyards might appear unrecognizable. Here, thick, tree-like stalks go deep into the ground, in search of underground streams which come down the mountain. The unsupported branches are heavy with bunches of grapes and are set to be harvested the next day.

The vines are a winemaker’s dream: indigenous varieties—many without official names—on their own rootstock. The location is so remote that these vineyards are phylloxera-free. (Around the world, most wine is made with grapes grown on vines grafted onto American rootstocks, which are resistant to the aphid that has decimated vineyards since the 19th century).

The wild temperature swings on the mountain—as much as 15 degrees Celsius each day—make for slower maturation times and more complexity in the glass. “We have a volcanic soil, with lots of minerals,” says Hirsch. “In the night it’s 14 degrees, in the day it’s 30. This adds to the aroma and all of these things.”

The viticulture, is practicing organic.

“In the beginning, there was a little bit of sulphate used in the fields,” says Hirsch. “Slowly we went down. We were afraid to do it completely without. But now for three years now we are completely without sulphate.” Today, the only input in the vineyard is goat dung, which is piled up in a small mound.

We’re met in the vineyard by Nariye Yeşilgöz, who along with her husband Adem manages Gelveri’s four vineyard sites, one of which they own. Today Adem is in a nearby town, selling their table grapes in the local pazar. As we walk around the vineyards, Nariye picks fruit for me to try from the garden. Hirsch and Özkaya have slowly convinced Adem to plant trees and other plants for greater biodiversity. Like using no sulphur, he was reluctant to at first, but he’s since come around, using one of the vineyards as a sort of test farm.

For Hirsch, Gelveri Manufactur is a model business, the sort of community project he spent 40 years doing around the world with WWF. He wants to show Turkey that a single family of farmers can earn a comfortable income making wine with traditional methods that are ecologically responsible. To help propagate this idea, Hirsch and Özkaya routinely host students from two nearby universities. One student did her dissertation in food science comparing their wine to conventional wines. Interest is growing, but so far no one else has tried to make wine with antique küp in Turkey, at least not commercially.

Back at their house, the three of us are tired from walking the wind-swept slopes, and sip some more tea. Hirsch for the first time during my visit starts to look his age. He steps away to take a phone call—a documentary film crew that wants to visit—and Özkaya talks to me in Turkish with hushed tones.

“Inşallah, we will continue to make wine for years to come. We still have our health, but you never know. We’re getting older,” she says.

Hirsch, for his part, still has work to do.

“As a nature conservationist I feel it’s necessary to save at least a few [of these grapes] and to make them known by producing a very good wine,“ says Hirsch. “Turkey has more than 800 unknown grapes. It’s such a genetic richness. I think if European winemakers knew that, they would be here.”