A kefir cliché is what I’d call my first encounter with the fermented drink. In 2001, while I was living in Vermont, my housemate’s mother, on a visit, stocked our refrigerator with products from the local natural food co-op. On the upper shelf I remember seeing a bottle containing what appeared to be lavender-tinted milk mottled with blueberry skins. The kefir was familiar to my housemate, who had grown up near Woodstock, N.Y., the daughter of a folk-singer-songwriter duo. But not me. I spent my childhood mostly in suburban New Jersey, and wouldn’t even take a whiff of it, despite being surrounded by seasoned kefir drinkers and the equanimous Green Mountains. I would only come to appreciate fermented refreshments years later, following a protracted acquaintance-making. It began trepidatiously with visits to Tasti D-Lites in Manhattan (if Carrie Bradshaw did it…), and exploded after moving to the Netherlands, where quark provided a gateway to yoghurts of varying viscosities.

Which brings me to today, where in Amsterdam, kefir has made a comeback. Not unlike other cities around the world, people here have been filling their kitchens with the stuff, among other DIY-ed creations in the art of fermentation. Kefir is no longer the exclusive remit of borscht circuits in the Caucuses and the Catskills, hippies, or the Scandically inclined.

And the evolution is epitomized by the emergence of Pét-Nat Kefir, a water kefir-based drink with a pétillant naturel property similar to sparkling natural wines getting that same description. Served as a non-alcoholic alternative in restaurants and wine bars around the Netherlands, Pét-Nat Kefir is produced by De Kefir Fabriek. Floor Overgoor and Yannick Slagter established the company in May 2016, alongside YanFlorijn Wijn, their Amsterdam-based wine import business, which this summer celebrates a five-year anniversary.

I spoke with Overgoor and Slagter at their tranquil home in Amsterdam Oost, where a backup batch of kefir had been fermenting for a couple days, and where they served Pét-Nat Kefir in wine glasses. Each sip offered simultaneous complexity and subtlety, effervescence, and the pleasures of sobriety—not to mention new understandings of how, where, and by whom kefir might be consumed.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Sprudge Wine: How did Pét-Nat Kefir come about?

Floor Overgoor: We had been making kefir at home after looking for an alcohol-free alternative to wine, something to pair with food, especially, because juices and sodas are very sweet and also quite heavy on your stomach.

Yannick Slagter: When you’re a wine importer, it’s very easy to just grab a bottle every night at dinner. Actually, alcoholism is a recognized risk of the trade, so it’s something to be careful about. So really, we were looking for an alternative first for ourselves, to just drink at home.

For many people, kefir brings to mind a yogurt-like drink. Pét-Nat Kefir is hardly like that. Can you explain?

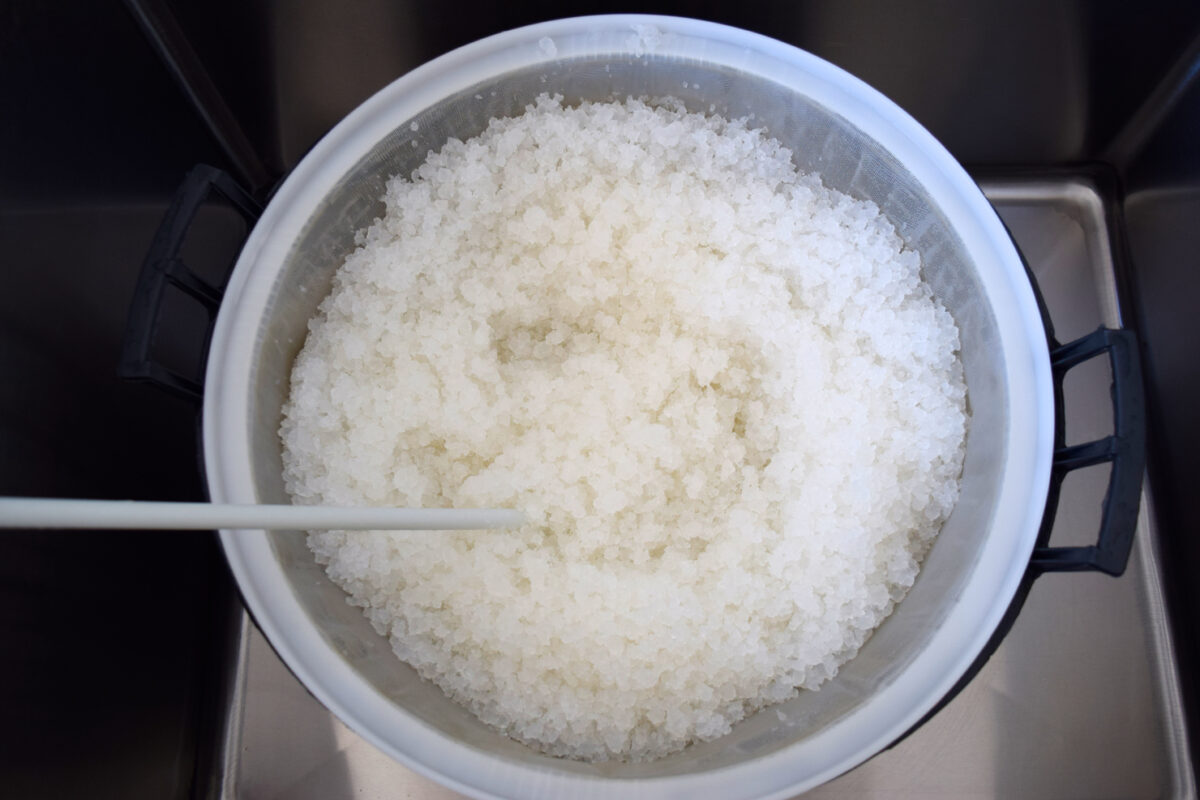

FO: You have milk kefir and water kefir—two different kinds of kefir grains, which appear to be a jelly-like combination of yeast and bacteria. From the milk kefir, the basis of which is milk, you get the yoghurt-like drink. From the water kefir, the basis of which is water, you get a champagne-like drink. Both types of kefir live off sugar: either sugar in milk or in water kefir, sugar from fruit or sugar that you add. The yeast breaks down the sugars and the bacteria converts the sugars into lactic acid.

YS: Pét-Nat Kefir is just water, kefir grains, dried apricots, lemon, and sugar.

This jar here, with the floating apricots, how long has it been fermenting?

YS: Two days now, maybe. But it’s really just a backup in case something goes wrong with the grains we now use at our production site, De Kefir Fabriek (“the kefir factory”), to make the large batches.

FO: Batches like this keep growing all the time, so the kefir becomes more and more. We first started with 20 grams of kefir grains; now we have about 20 kilos.

What prompted De Kefir Fabriek’s move into an actual production site?

FO: We had to find space and also equipment to do it, because there’s no one else that makes kefir large-scale that we know of. So we had to find a lot of things on our own. That took some time, but now we have our own little kitchen that we only use for kefir, nothing else.

YS: We just pulled equipment from everywhere; some parts are from brewing beer, some parts are from making cheese, and then we put that together to make a fermentation setup for kefir. Every two days, we can now produce about 50 liters of Pét-Nat Kefir, which comes down to 60 bottles.

So Pét-Nat Kefir is healthful, but not necessarily promoted as a health drink?

FO: There are different health benefits. One is the bacteria—the probiotics are good for you. But another one is that hardly any sugar is in it, so it’s also what’s not in there that’s healthy.

YS: Our main market is restaurants, so we wanted it to appear more like wine. We promote it as an alcohol-free alternative to wine. It’s also healthy, if you’re interested in that, but it is in a champagne bottle, it has the crown cap, and it’s called “pét-nat.” We wanted to keep the link with the natural wines that we import. The name seemed fitting when we thought about how when we bottle it, there’s no sparkle—there is no CO2—but after we put it away for some time, for about a month, it just continues fermenting in the bottle, giving it the CO2. And then it becomes pétillant naturel. It’s a similar process to what happens with pét-nat wines.

How did you get into importing natural wines, specifically?

FO: We both were interested in sustainability issues and wine, which is how we started to import organic wines. Then we learned more and more about wine, and got interested in natural wines. About 80% of what we now import is natural.

YS: Talking to winegrowers, we learned more about what they can do to the wine to turn it into what they want it to be. But a lot of the winegrowers we met were trying to make low-intervention wines, so no additives, no filtration, not clarified using animal-derived products like gelatin.

What about natural wines did you find most interesting?

FO: Both how they make it—it’s all just grapes fermenting with wild yeast—and the process, in that they don’t add anything. In the vineyard, you see the difference. A biodynamic natural vineyard is very alive, with a lot of flowers and herbs—it is much more healthy. A conventional vineyard is just grapes—a monoculture.

YS: In a monoculture, they have sprayed all the weeds and herbs with chemicals because they’re competition for the vines. For example, if there’s a bug eating the grape, you spray all the weeds and the herbs, but that makes it very unattractive to birds, which then won’t be there to eat the bugs. But in organic biodynamic vineyards, the ecosystem keeps itself intact, so you don’t have to spray pesticides. If it’s a healthy environment, it will keep itself in balance. It’s way healthier for the environment, so it’s just really a lot better for the world. Besides that, I think that the wines are way more interesting when they’re fermented on their own indigenous yeast. They become more light, and if you don’t kill the wine with a lot of sulfur, they’re more vibrant, alive, and energetic. Everyone now wants natural food—not processed, no additives—and I think the same should go for wine. In a conventional wine, if you were to list all the additives and things that could be in there or that could have been used for making the wine, they wouldn’t fit on the label.

Pét-Nat Kefir’s list of ingredients is indeed short. For non-Dutch readers, can tell us what else the label says?

YS: There’s an explanation that it is fermented. We call it a “frisse drank” (Dutch for “fresh drink”) instead of a “frisdrank” (Dutch for “soda”) that is low in sugar. There’s only about half a gram of sugar per 100 milliliters, so it’s drier than a white wine. It then says that the bit of acidity and complexity make it good for pairing with food, but it’s also just nice to drink on its own. And it says that it’s a natural product, so each bottle can differ a little. It should be kept cool and drunk within five days after opening.

FO: José Luis Garcia, the person who made the logo for Glouglou, also made this one.

Have you noticed that people seek it during some seasons or for some occasions more than others?

FO: It’s more popular in summer and also around Christmas and New Year’s Eve.

YS: In Amsterdam, at Bar Centraal, the new bar from the people behind Glouglou, they sell it well, especially in summer or this kind of warm spring we’ve had, because they serve it outside, in the sun. But at 4850, which has a very extensive list of champagnes, sometimes people come for lunch and they don’t feel like drinking champagne yet. Then they’re really happy with Pét-Nat Kefir because it’s similar and they can—

FO: —have the same feeling and experience. It’s something special.

What about mixing Pét-Nat Kefir?

FO: There’s a restaurant in Amsterdam that works with our kefir in cocktails and they are also very happy to mix it into a non-alcoholic drink, The Lobby Fizeaustraat in Hotel V. We have made quite some cocktails, too. It’s really funny if you make a mojito; with all the lime, sugar, and mint, you really think you’re drinking alcohol because you can’t really place the taste. With orange juice, as a mimosa, it’s really nice. And cosmopolitan-style, you really get the feeling that you’re drinking alcohol—it has the deep flavor. In the summer, coffee with kefir is refreshing as well—

YO: —especially with cold-brew coffee because it’s more floral, more aromatic—

FO: —not so much the bitterness. With the Pét-Nat Kefir, you get something fruity and really nice.

Consumers in the Netherlands can order Pét-Nat Kefir (for about €4.50 a bottle, depending on quantities) by emailing proost@kefirfabriek.nl. Plus, you have a distributor in Belgium: Terrovin, run by Wouter de Bakker. Can readers nowhere near the Benelux get some?

FO: Not yet. It always needs to be refrigerated, so that’s why we can’t really sell it outside the Netherlands. It’s OK when it’s very shortly outside of refrigeration, but it keeps fermenting, so if it’s too hot for too long, there will be too many bubbles.

YS: Well, it’s completely dreaming, but it would be nice if we could make a franchise—if, for example, someone in Spain or Los Angels or wherever could make the same product, use the same label, use the name, and then distribute it. That would be cool.

Karina Hof is a Sprudge staff writer based in Amsterdam.

Photos by the author unless otherwise noted.