I arrive at Curto Cafe at around 11 a.m. on a Monday to talk with Gabriel Magalhães, one of the co-founders. Curto, a collaborative, innovative coffee shop in downtown Rio, is a bit unusual: there are no prices, the owners simply have a board where they write the costs of what they need on a monthly basis to sustain the business and leave the rest up to the customer. At the time I arrive, there are nearly ten customers and Magalhães knows them all by name.

Magalhães tried coffee for the first time six years ago when he started helping his uncle in his coffee shop operation in Volta Redonda, in the state of Rio de Janeiro. After asking many coffee suppliers in Brazil to try lighter roasts and being told it was not commercially viable, they decided to invest in roasting themselves, by setting up a roasting facility inside a small coffee farm in the state of Espírito Santo. They also bought a La Marzocco GB/5 espresso machine and left it there, so that the producers could, for the very first time, have an espresso made with their own beans. During the process, they trained Mario Zardo—a former coffee cherry picker—to roast coffee.

In 2011, Magalhães returned to Rio and founded Curto Cafe along with his two other co-founders, Sergio Kienteca and Rômulo Martinez, in a four-square-meter space of a commercial building. They set a “fair price” model, charging very little for espressos and cappuccinos and even less for those who could not afford it. Initially, their equitable business plan seemed to be working, until their lease was up and the building wanted to charge four times more for rent. Through the power of their story, they were able to secure a larger space in the same building thanks to informal crowdfunding on Facebook.

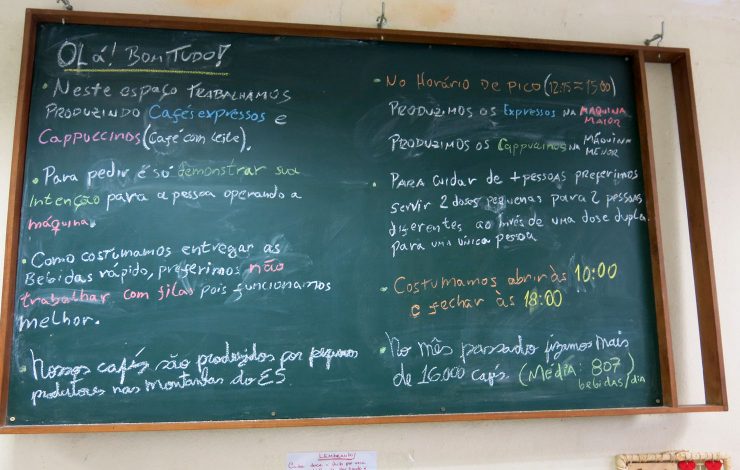

After moving, Curto also decided to radicalize its collaborative business model by getting rid of prices altogether. Charging customers felt impersonal and obligatory. The owners didn’t just want to run a business, but instead wanted to connect with their customers and create a space where they would also interact amongst one another. So they came up with a trust-based system: you order and get your drink, then look up the cost of it on a blackboard (everything is there, including the amount of their salaries), and then it’s up to you to leave what you want in a bucket. Customers are also encouraged to put a poker chip in another bucket, indicating what type of drink they had (espresso or cappuccino), so that Curto can have some control over its inventory.

They also sell coffee beans, which are paid for under the same scheme. Rômulo tells me that some people wrongly assume that they are a coffee shop where you can pay R$0.50 (about $0.15 US) for an espresso, but it’s more than that. It is a space where relationships are born and nurtured in a fluid way, where free exchanges happen based on one’s own parameters, perceptions, and financial reality.

I’m curious about how they split the earnings. Magalhães explains that the six people who currently work at Curto have different living costs, and thus get different salaries according to their needs. The extra earnings are usually allocated to paying debts, which are also displayed on the cost boards, or are reinvested in the coffee shop and Zardo’s roasting facility.

Curto’s exchange model has been working perfectly for two and a half years now. Zardo, who used to make US$0.14 per kilo of harvested coffee when he was a coffee picker, now makes twenty times more than that per kilo of his roasted coffee. He has built a solid relationship with several small producers from Espírito Santo, from whom he buys and pays more than the local middlemen.

By 12:30 p.m., there are roughly eighty people lining up at the two La Marzocco machines in Curto: one for espressos and one for cappuccinos. Magalhães heads back to help his fellow baristas. People are greeted by their names and some bring their friends to taste the incredible, almost magical coffee that is made here. The ones who are introduced to the paying scheme get skeptical: this can’t work in Brazil! After spending a day here, I can attest that it does. Magalhães and his partners have proved it to me, not only in their high quality coffee, but also in the way that they have created a space of belonging, and being a part of something special.

Juliana Ganan is a Brazilian coffee professional and journalist. This is her first feature for Sprudge.