Ian Williams worked his way up from janitor to shoe designer at Nike, then left it all to start his dream cafe: Deadstock Coffee, a hub of Portland design talent and cultural force located in the city’s Old Town district. Self-described as “snob-free coffee,” a single guiding mantra drives Deadstock: “Coffee Should Be Dope.”

It’s a sentiment that’s hard to argue with, and the coffee—roasted by Williams himself, at Portland co-roaster facility of note Buckman Coffee Factory—is indeed delicious. A sharp focus on accessibility runs throughout the menu, which includes house specials like the “Lebronald Palmer” (a blend of coffee, sweet tea, and lemonade) and the “Charged Up” (green coffee extract and Green flavor Kool-Aid). “I don’t really do light roast,” Williams tells me over a mug in the shop’s busy entryway. “I just want to make good, even, mellow coffees.”

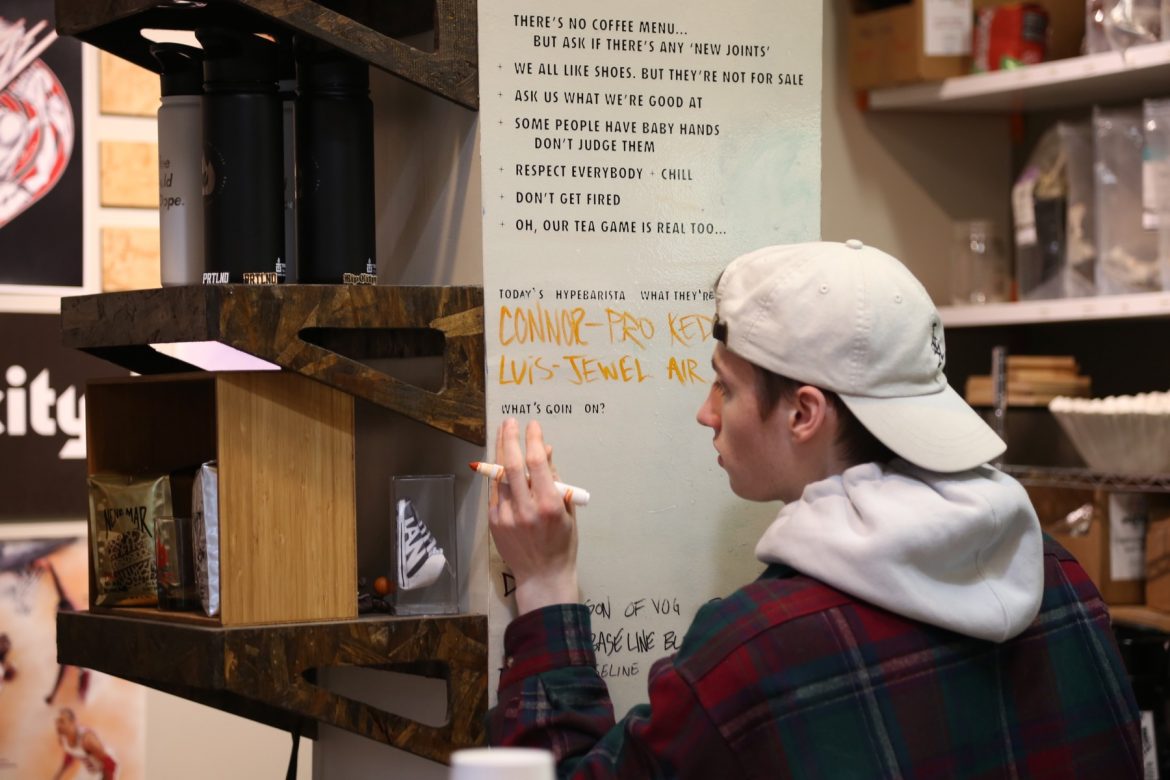

Conversations here are punctuated by greetings, departures, and casual updates from regulars, making for a space that feels alive with vibe and running dialogue. People talk to each other at Deadstock. A whiteboard next to the cash register records the day’s specials, the current soundtrack, and what the staff is wearing on their feet. You want to look nice showing up here, in a low key way. Come wearing something you like—a pair of shoes, or a coat, or a cool t-shirt—and Williams and his team are bound to notice, and use it to jump off a conversation.

Over a series of visits for this article I meet, in no particular order, multiple local artists, writers, local coffee heads, the leader of the neighborhood council, the landlord, the barista’s dad, various other stylish Portlanders of a creative extraction, and Williams’ own mother, who bakes the shop’s mascot pastry: Butterscotch Trap Cake. It is a riff on poundcake, tea cake-like loaf of textual duality, with a crunchy top and deeply satisfying golden base. (You may be asked to decide between an end piece and a centerpiece. There is no wrong answer.) There are typically at least three to five designers in the shop at any time, easy to spot by the stickers on their laptops and two-at-a-screen flow of revolving meetings. More work gets done in this space than just about any other venue in town, including actual offices. The music is always good.

Coffee fuels it all, but in a subtle way—you don’t have to know everything about coffee to feel good here. It is absolutely unlike any other cafe in Portland right now. I mean that as a compliment.

There is a seamless blending of coffee and sneaker cultures, which feels effortless in Williams’ hands, but is the stuff a thousand design decks are made of. What they’ve found at Deadstock is an expression of the cafe space as a unique statement, a conduit for a unique individual voice, rarer than any ungettable nanolot Gesha. Indeed, each day to its dedicated clientele in the heart of Portland’s oldest neighborhood, Deadstock is sourcing and serving the scarcest of coffee commodities in 2018: originality.

I spoke with Ian Williams about his time at Nike, how he parlayed that into starting Deadstock, and the shop’s deep bench of influences and collaborators. “It’s about the people in here,” he tells me, and as if on queue another regular walks through the door. We’re introduced, we shake hands. The conversation grows.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Ian Williams: Hey, this is nice! [Points to my shirt] This is from Patta, and you got the Coq Sportif‘s on…

Jordan Michelman: Thank you. I feel like I have to look cool coming in here.

Yeah, we like that. That experience and people chilling is more important to me than what goes into the cup—which is different from what you guys usually cover on Sprudge—but hopefully what does goes into the cup here is fire.

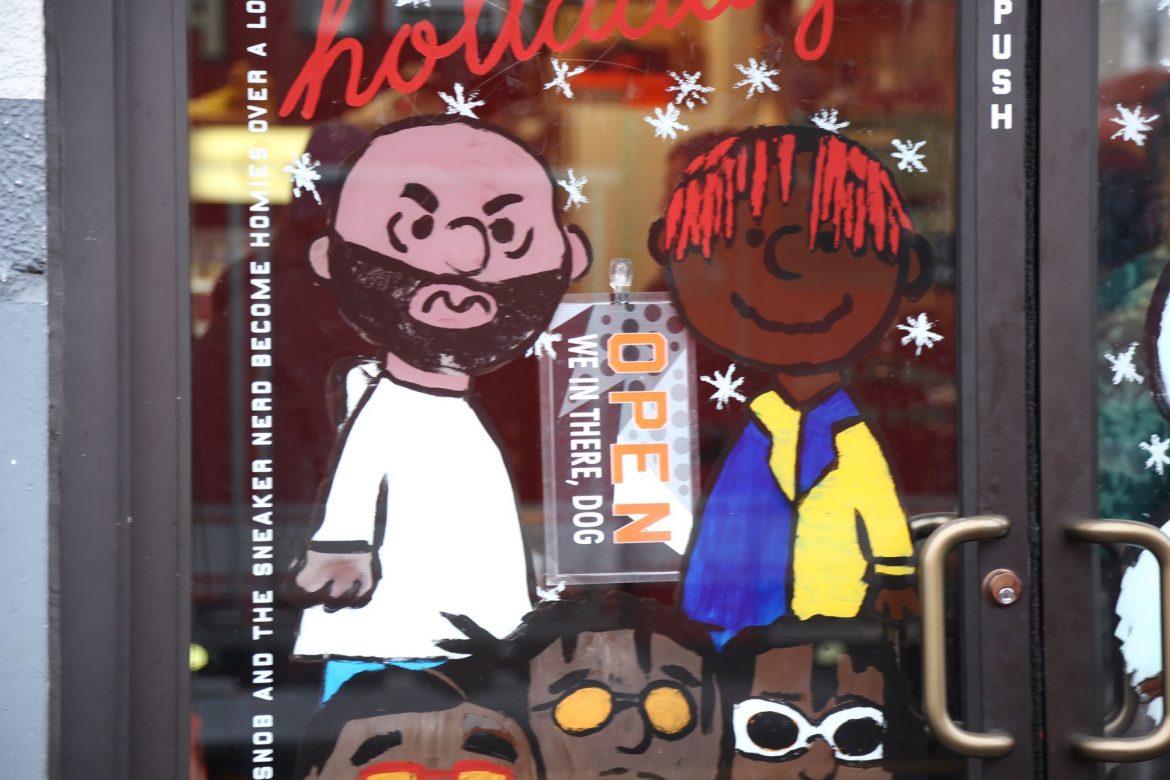

Who painted this Charlie Brown scene on the door?

That’s our “Trappy Christmas” display, painted by the brothers, Connor and Chandler Radonich. It’s got Joe Budden, Lil Yachty, Migos, Kodak Black—rappers as Charlie Brown characters.

How did you meet the brothers?

I’ve known them since they were 13, 14—their mom would drop them off at Index and we would be like, okay, we’re responsible for these kids. They were always kids that had a lot of questions. And one day they came in here, doing work for Compound across the street, and they came in and said they wanted to learn how to design, and so I said, if you work with me and do design work with me I’ll teach you how to do illustrator and photoshop—I’ll help you get to production ready work. Now they’re 18, they started when they were 17, and this is all they do now. They’re even starting to do design work for other coffee companies. We want to do dope stuff with our friends. That’s all that really matters.

When did you first move into this space?

February 2016. This is the old 24 Hour Church of Elvis. The landlord of this building is the same guy who owns the building that Compound is in, and at first, we were looking at the space right next door to Compound, but that space is like 3,00-square-feet, and the landlord said no. But he saw that I was working towards something and he had the idea to open something in this space. So we took it, made it larger—part of it was a hallway, part a garage—and we made it one space.

He was just like super helpful, the landlord, his name is David Gold and he’s really accommodating. All the people in all the buildings he owns are good people. He’s really about helping out artists and people who wanted to do good things for the city and community and culture. It’s pretty cool.

Tell us the story about your time at Nike.

I stated at Nike in 2006, working retail in their employee store, and left after the holidays were over, but it made me realize I wanted to do sneakers as my life, not just as a hobby. Growing up, I was a big Allen Iverson fan—still am—and whatever new shoe he had coming out, I had to have it. I would get one new pair of shoes a year, and that new shoe would be my school shoe, and the old shoe would be my play shoe. I grew up out in the Hillsborough/Beaverton area, and Nike was right there.

I was trying to figure out how to get back in and found a temp job making airbags—you know, the air units that go in the shoes. They actually make ‘em here and ship ‘em overseas and then they get put in the shoes. It was the worst job ever. But then I found out about this janitor job on the Nike campus, and I knew I would be seen. So I took it, and just kind of ran from there.

How did you make the jump from janitor to designer?

Well, I worked as a janitor first for like three years, before I found out about an open designer job. At that point, I had made friends with a lot of people. Those three years as a janitor, I used it as my college—I didn’t go to college—but I worked my through Nike, asking questions, coming in early, giving myself a desk in the hallway, whatever hustle things I could do. If a designer needed a closet reorganized, I was there. People who saw me during the day had no idea I wasn’t in footwear. Most people thought I already worked in footwear, but at night I was a janitor—most people didn’t see that part.

My whole Nike career was like one big, smooth stretched truth. You know, like, someone asking, “Ian, you know how to do that?”—hey, of course I do! [texting motion] Meanwhile I’m Googling on the side…

After you advanced, what was your favorite part of working in footwear?

Well, I got to do some cool stuff there. I actually got to design a shoe. It’s a Nike SB, inspired by the wet floor sign, the slippery sign. The guys who worked in skate, I said, “Let me do a shoe” and presented them with a three pack, all inspired by working as a janitor. There was a wet floor sign shoe, a Windex shoe, and a vacuum shoe. They picked up the floor sign.

How many did they make?

They did 5000 pairs—they’re starting to pick up in value now actually. It’s because I’m famous (just kidding)—you know, for most of the pairs, people bought them and beat ‘em up, but there’s a few left that look nice. My payment was they gave me twenty pairs, and I gave ‘em out to people along the way, people I had asked design questions, or people who let me do stuff like clean closets or have that desk in the hallway. I have just two pairs left now.

When did coffee come into your life?

In maybe late 2013, or 2014. Nike was cool and all, but I started getting kind of restless with the way that everything was going. It was just super…structured. I thought once I got into footwear it would be more laid back and about the people, but around that time I started curating these art shows, doing side events, inviting my homies to put art up for it. I wanted to do events and put a brand together for a style of chilling that wasn’t work. We had done like three events, a house party, a couple of small things—single day pop-up events—and that was definitely a lot of work. I started to think like, maybe I should open a gallery… but galleries don’t make money. What makes money? Coffee shops.

A coffee shop is a place you can go where you can have a meeting, have an interview, go on a date, catch up with somebody, sit by yourself, get work done, go with a group—I wanted to create a place where it’s okay to loiter. You can’t do that in a shoe store. The only other thing was a bar or a club, but that excludes young people, and if we want the footwear industry to thrive you need to give young people access to it.

From there, how did you make the decision to get into roasting? Was it an aesthetic decision or more practical?

I just started roasting February of this year. I started out with Dapper & Wise—I have a mentor from high school who is really close with those guys, and they’re from Hillsborough. I didn’t really drink coffee when this space opened! But I have a friend named Sarah Cooley—we call her Breezy—and she LOVES coffee. In the early days she would go with me to try coffee places. She was the one who helped me with Dapper & Wise, and they’re cool people, their coffee is good. They opened a new facility in Hillsborough with rental space and she was helping them connect with Nike and hold meetings there.

At the end of 2016, beginning 2017 we had all that bad weather here in Portland, and our business dropped like a quarter of what we’re doing. Right before the holidays we ordered a bunch of coffee to give out as gift kits to influencers and what not, but then the weather hit and I wasn’t able to pay dapper, and so the only thing I really could do was start a new account or figure out a roasting thing and pay for it as you go. Buy green, pay hourly, figure it out, and use the money it would generate to pay Dapper back.

So it was not your dream to be a roaster?

I said I would never roast! But in all honesty I’m really competitive. I said, if I’m gonna do it, I’ll be really good at it. I’m not concerned at being the greatest but I don’t want it to be something where like, yeah, the coffee is okay. I want people to like it. My whole coffee roasting model is “coffees that work”—nothing that fights with milk, nothing that’s going to turn people away. I just want to make good, even, mellow coffees, roasted medium to dark. I don’t really do light roast.

How would you describe the design feel of this cafe?

I think most coffee shops are an interior design competition. If you are a coffee shop in Portland, and this is no diss on anybody involved, but if you don’t use Bee Local Honey and Jacobson Sea Salt and Woodblock Chocolate and a lot of these other companies, and your walls aren’t white with a crazy looking espresso machine, and you aren’t playing super mellow whatever music, you don’t fit in the coffee world here. But I don’t like any of that. That’s not for me.

I just really… you know, a lot of the reason why I opened a coffee shop was because I didn’t feel comfortable in all these other places. I wanted to hang out with my friends who moved to Adidas or Under Armour, and there was nowhere we could hang out during the day that wasn’t alcohol, and I don’t drink. I felt like—to me, all these coffee shops suck, and so instead of complaining I made one. A place where I would feel good, my homies would feel good, and other people would feel good. When people come in, we make them feel good—even to just be like “wassup?”, that feels good. And we will joke on you, most definitely. If we’re not joking it’s weird in here. A lot of people describe us as like a high school bedroom, with posters and things like that, and there’s so many people that come through and they’re like, “Whoa, I used to have that poster,” or “I never thought of such-and-such art this way.”

It’s such an intimate space, and everybody is everybody’s friend. We bank on customers knowing each other. It’s a small space. If you’re waiting in line you aren’t twiddling your thumbs. Customers really know people’s kids, and you know like, somebody maybe just had a job interview, or whatever, and we all talk about it. It’s about the people in here.

You still have a gallery component to the space right?

Yes! We have a show from the homie Nate Corrado, who still works for Adidas. We rotate the show out every month or two. The one we did for Sneaker Week was very popular—we took shoes and cut them open, deconstructed them, so people can understand and see inside. We always see shoes as what we buy and what comes in the box, but you never see the components of what they are. So instead of just putting colorways on the wall, I wanted to do more education. The next collaboration features a coffee bag, a shirt, a mug, and vinyl toys all done together with an artist— he’ll paint the walls and everything—from an artist I’ve been following for many years named Perez Westbrooks, who goes by Gaijin.

This cafe is a fusion of coffee and sneaker culture. Obviously you sell coffee here—why don’t you sell shoes?

For a couple of reasons. One, we’re right in the heart of the sneaker community here in Portland, where the sneaker culture lives. Within a few blocks we have Compound (retail), Index (consignment), Unspoken (new and up and coming), Upper Playground doing street art t-shirts, and then we have Pensole. The only sneaker design school in the world is on the other side of this building, run by my mentor at Nike. If we sold shoes at Deadstock we would be competing with our friends.

The other reason is that in Portland specifically, everyone has access to discounts. Nobody pays full price. We would just be a random store here selling random product, and Portland can’t support that. There’s a lot more tourists coming now, and more people moving here, but nobody needs anything in the sneaker world. I think it makes us a more authentic space—we’re not a shoe store. We’re a coffee shop and a community space, and we happen to be serious about shoes.

What’s your sneaker white whale? The sneaker you’ve always wanted to find but have never been able to bring home?

We call ‘em grails, like a Holy Grail. My grails are actually all relatively inexpensive compared to most sneakers. They’re shoes I really, really like, but I need to find them for the price I want to pay. The shoes I love go for maybe $200 or up to $500, $600, which is expensive but compared to other stuff in the shoe world? People pay ten, or even twenty thousand dollars for sneakers all the time.

That’s wild. That’s like wine nerd wild.

Yes. But so, for me, there’s a Pharrell NERD Dunk that got made in like ’03, i think, or ’04. It’s an all-black Dunk high with the NERD brain logo on the heel, and that’s it. I want them so bad. There’s another pair of Dunks called Dinosaur Jr., named after the band, and they’re all silver with a purple swoosh and it says “Dinosaur Jr.”—I also want them so bad.

There’s another shoe called the Ray Gun Home or Ray Gun Away, which is based on like a fictional basketball team that Nike made. They did a pair of SB’s, the home color—usually home is light, away is dark—but they flipped it so home is dark, away is light. Every time I see them I get really, really sad—I really want those.

And there was another shoe, too, called the Purple Pigeon: all grey, Dunk low, with hints of light purple. Index has a pair right now and I said “how much” and they said “$350” and it’s like…well, I would pay $200, or $250 maybe, but not $350. And I used to own a pair! I lost ‘em. For the longest time, Purple Pigeons were out there going for like ninety bucks. And now, because I want them, they go for $350. I still look for them when I got to my mom’s house.

These are the shoes that are really important to me. For other people it might be like, “Okay, big deal,” but to me it’s like, “Yo, I NEED this.”

What’s next for Deadstock? We heard something about maybe a collaboration with Wrecking Ball Coffee down in San Francisco—any other collaborations in the works?

We’re still trying to figure out something with Wrecking Ball. Right now we’re a bunch of people who like sneakers and mess around with this coffee thing. But you know, it’s a conversation that I always have—we call each other coffee homies. We’re sneakerheads who work in the coffee industry. One of our biggest thing is making coffee not so pretentious. So for us, it’s about aligning with people who share our sentiment—people who feel comfortable with doing an event that’s a little bit different. During Coffee Fest here in Portland there were all these events that are like, coffee triangulations and latte art and stuff, but we did a karaoke party instead. Whatever happened to people coming together and hanging out?

Whatever we do next, I want it to be a reflection of my vision—our vision—and what the community needs, what I feel the community needs. That’s way more important to me than opening another shop. And even if we were, as I look for opportunities, you know, I feel like I could open out on SE Hawthorne and we would be successful, or in the Pearl, you know, we’re cool, and it would be a busy space—but what does that community do for us? What are they doing for us? The neighborhood? So making sure the next place is somewhere we can work together is way more important.

I’ve had offers to be purchased now. One of the first offers for investment would have required us to open up in SF first, not Portland. But we couldn’t do that because for this to be a coffee shop that is sneaker themed and inspired by this culture, we can’t be from somewhere else. This is where the culture is. It’s the sneaker capital of the world.

And this way here, your mom can still bake the cake?

Yup, my mom bakes the cake we sell here. Butterscotch Trap Cake. It’s so real.

Jordan Michelman is a co-founder and editor at Sprudge Media Network. Read more Jordan Michelman on Sprudge.

Photos by Zachary Carlsen for Sprudge Media Network.