It’s been 14 years since the Geisha coffee variety dropped into the specialty coffee scene on the 2004 Best of Panama auction stage. Since then, the variety has broken records on auction prices multiple times, helped secure wins at barista competitions, and astonished palates for people around the world.

But here’s the issue: it gets confused and punned with geisha, the Japanese entertainer, which leads to many problematic interpretations. What some might consider a delightful homophone has become a kind of carte blanche for inappropriate appropriation—taking images and motifs associated with the Japanese tradition of art, song, and dance, and using it to sell high-priced coffee.

The misuse of “geisha” in this style is nothing new, nor is it a relic of yesteryear. In researching this article I came across multiple roasters using Japanese geisha images to market their coffee. Similarly, there are articles written in the last three years with geisha people imagery illustrated next to Geisha coffee.

Not only is this misuse disturbing, but it is wholly unnecessary. By the time Geisha coffee made itself known to the greater coffee community, geishas were already known to the world as something else. The region from which this coffee hails, however, and the traditions to which it is tied, are hundreds of years old, and instead go by the similar-sounding but importantly different name of “Gesha”—hold the i.

I’m writing this editorial to offer a bold choice to coffee drinkers, roasters, importers, and industry professionals of all stripes around the world. What if we just stopped calling it Geisha? I posit that the industry should choose to use Gesha instead, in perpetuity moving forward, and to abolish “Geisha”—and all of its unfortunate linguistic abuses—to the grounds bin of coffee history.

There’s several potential advantages to this choice.

- Consumers new to Gesha coffee will no longer assume that it’s named after the Japanese geisha performing arts tradition.

- We can hopefully, and definitively, avoid seeing any future instances of Orientalist imagery being used to market and reference this coffee.

- We can wax poetic about this truly delicious and inspiring coffee variety while properly evoking its Ethiopian heritage, and without confusing consumers as to its origin.

Before we get too far down the rabbit hole, let’s back up to what we know about Geisha coffee.

The Gesha coffee variety was “discovered” via British colonial expeditions in the 1930s in southwest Ethiopia, brought to research stations in Kenya and Tanzania, and then subsequently to Panama for its coffee leaf rust-resistant traits. In their groundbreaking previous work on the subject, coffee professional and journalist Meister explored the variety’s historical documentation in a piece titled “Is it Geisha or Gesha.” A certain “Geisha Mountain” was referenced in 1936 by those British colonials, but, plot twist: there is no Geisha Mountain in Ethiopia. Instead, there is a Gesha region of Ethiopia—an entirely separate term with no connection to Japan. How exactly the “i” came to find its place in coffees from Gesha is a matter of some conjecture. It may have been a simple misspelling. It’s also possible that because the local language Kafa is oral, it was romanized into “Geisha.” There’s also a third theory that the researchers used “Geisha” because it was a more familiar word and exoticized it. Since we weren’t there and documentation is not clear on why it was written as Geisha and not Gesha, we’ll let these theories lie here.

In 2004, the Peterson family of Hacienda La Esmeralda submitted Geisha coffee and won the Best of Panama auction. The winning bid was $21 per pound, which seems like nothing compared to this year’s record-setting $803 per pound. Geisha seeds were introduced to Panama from a research station in Costa Rica. The coffee was spelled as Geisha—and still is by many producers—because that’s what they were documented as in the original expedition.

The Panamanian “Geisha” coffee has origins to Ethiopia. In a 2014 genetic research study of Geisha coffee in Panama and Ethiopia, Dr. Sarada Krishnan, Director of Horticulture and Center for Global Initiatives at the Denver Botanic Gardens, found the two coffees to be genetically very similar. She wrote, “It is highly possible that the Panamanian Geisha could have originated from the same Ethiopian Geisha coffee forest as the samples for the present study came from.”

As the variety spread around the world, other producing regions wanted to replicate the success of the Panamanian “Geisha” coffee. The variety grown in Central America tends to be spelled “Geisha” while other regions use “Gesha.” There is no established rule. Within the industry, “Geisha” coffee is more widely known and holds brand power, as written about by James Hoffmann and many others.

To summarize, all of the coffee we’re talking about—whether you use the “i” or not—is actually Gesha. Let’s move on to why this is all problematic—and please note that for the remainder of the article we’ll default to using “Gesha” when talking about the coffee.

Gesha coffees are rare, expensive, and often given notes like “delicate” and “floral.” If you were new to specialty coffee and just learned about this variety, it wouldn’t be too far a jump to unfortunately associate these same characteristics with the Japanese arts tradition. In Western countries, stereotypes about Japanese women lean into exoticism. They’re portrayed as submissive, delicate, and astonishingly beautiful. For geisha performers, the word came into global use in the early 18th century and it often mistakenly connotes an idea of a demure, high-priced prostitute. Books like Memoirs of a Geisha and Madame Butterfly have certainly enforced stereotypes and contributed to Orientalist perceptions.

Briefly, Orientalism is a concept introduced by a Edward Said in a book by the same name about how the West is centered and the East is perceived as “other” and exotic. In the West, it creates fantasy interpretations and representations of what the East is like. It’s a fascination with Eastern culture and shows up on the daily as turmeric suddenly being “discovered” as a superfood or Katy Perry dressed as a geisha.

“The concept of the geisha as perceived in Western society is fraught with exoticism and hyper-sexualization of Japanese women,” says David Inoue, Executive Director of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). Established in 1929, the JACL is the oldest Asian American civil rights organization in the US and according to their website, works to “secure and maintain the civil rights of Japanese Americans and all others who are victimized by injustice and bigotry.”

Inoue continues, “It is quite a stretch to use images of geisha to market a coffee that has its origins in Ethiopia, but is also symptomatic of our misogynistic society that continues to celebrate the objectification of women, particularly women of color.”

The coffee industry already fetishizes Gesha coffee. We package it up nicely into tins and small doses. It’s talked about in tones of reverence and introduced to customers at five times the standard cup price. Asian women are similarly fetishized (believe me—I am reporting from personal experience). If we’re not on parallel paths of the same word being used in similar ways, then the industry is certainly capitalizing–unconsciously or not–on Japanese exoticism.

Confusion abounds around the term. “I thought it was named ‘Geisha’ because someone thought it was so exotic and sexy,” a fellow specialty coffee pro told me, on condition of anonymity. This is from someone who used Gesha coffee in their United States Brewer’s Cup competition routine.

It’s not just baristas who get confused. Noboru Ueno, owner of equipment distributor FBC International in Japan, finds the use of the word “geisha” when referring to Gesha coffee to be similarly misleading in his country. Ueno says that because geisha artists are often symbolic of Japan’s culture, like Mt. Fuji and sushi, it’s easy to popularize it in consuming countries, especially in Japan. He found that Japanese consumers associate “geisha” coffee with Japan, and that coffee professionals typically do not try to correct the misunderstanding.

Ueno agrees that the correct term Gesha should be used going forward, as the coffee itself is Ethiopian, not Japanese. “Every consumption country, including Japan, must respect the original culture,” Ueno tells Sprudge. “Words and language are the fundamental basis for each nation’s culture.”

Respect, accuracy, and the dismantling of Orientalism and colonial primacy—these sound like pretty great reasons to drop that damn unnecessary “i”. You can argue around this a thousand different ways, and it all comes back to the same thing: it’s Gesha, not “geisha”.

Gesha is a coffee producing region in Ethiopia, from whence the popular Gesha coffee variety is thought to originate, same as the Chardonnay grape is named for the Burgundy village of Chardonnay, or Warsteiner beer is named for the southern German region of Warstein, or the brand Point Reyes Cheese is named for Point Reyes, California. We name agricultural products after the places they hail from all the time. In Gesha’s case, globalism conspired to move the fruit from Ethiopia to Panama and beyond, which has ended up being a good thing for coffee drinkers—these coffees are delicious!—and also a good thing for Gesha growers in Central and South America, whose coffees can fetch top dollar. However, these same global forces also conspired to introduce the “i”, making it sound more like the familiar word “geisha”—which is why today I have to look at exoticized, fetishized depictions of Asian women being used to sell coffee.

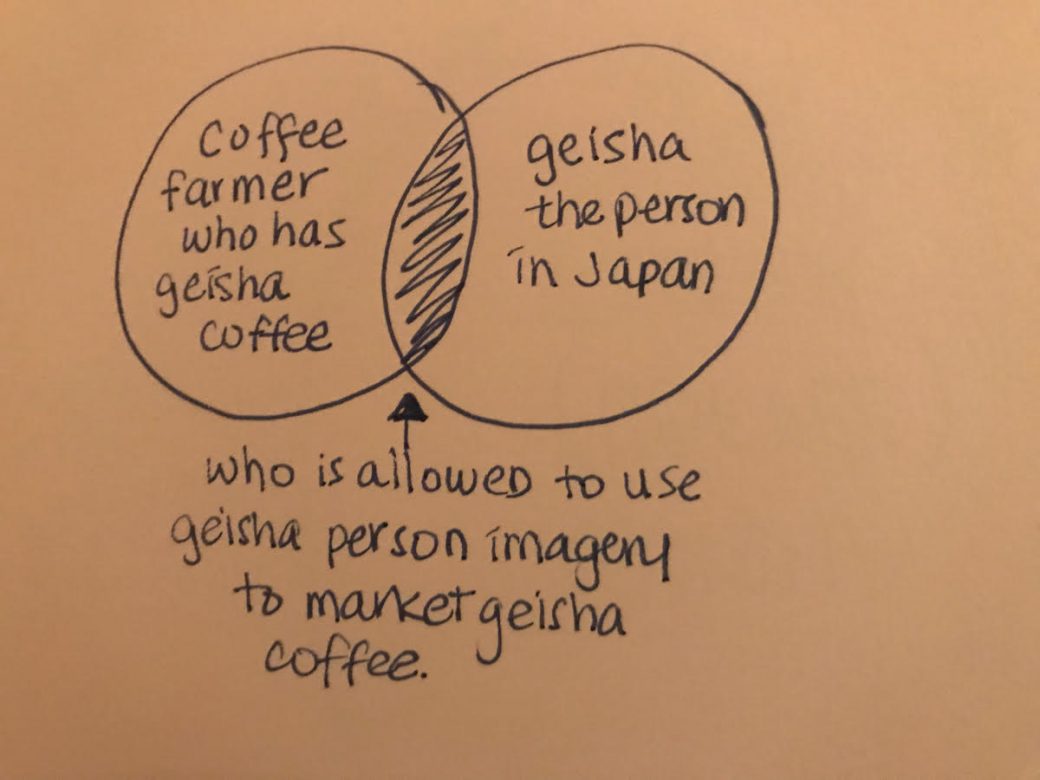

There is maybe only one scenario I can think of in which it might be genuinely appropriate to term something a “Geisha” coffee, and that is if the coffee was grown, roasted, or served by an actual Japanese geisha artist. In such a scenario I am all for using the term “Geisha” in relation to coffee—and I’ve created a handy Venn diagram below to illustrate this choice.

Words evolve. Their associations change. That’s part of the glory of the English language. And for all its glory, it is not without fault—sometimes words get written down wrong or exoticized, especially when the person doing the writing has all the power. But together we have the power back in our hands now. Using the correct term Gesha instead of the inaccurate term “geisha” helps remove ambiguous relations; it respects the cultural and agricultural history of the crop; it better informs coffee drinkers about that history; and it minimizes the likelihood of some asshole using a picture of a Japanese geisha person to discuss the coffee ever again.

So let’s call it Gesha, not “geisha”—it’s a small change with big meaning behind it.

Jenn Chen (@TheJennChen) is a San Francisco–based coffee marketer, writer, and photographer. Read more Jenn Chen on Sprudge.