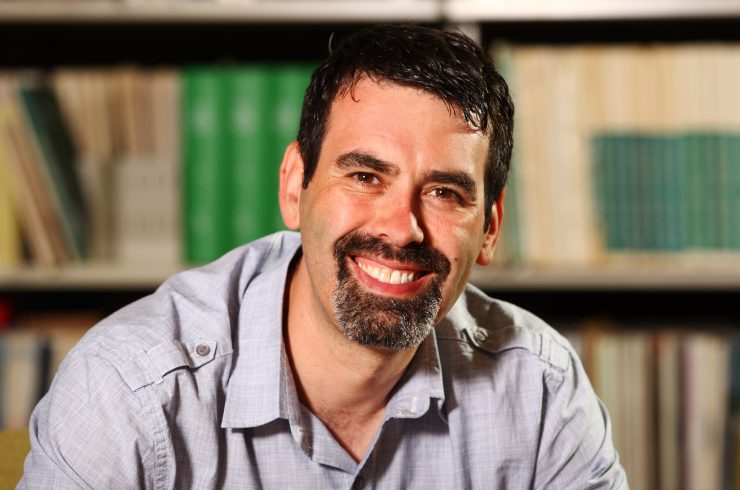

Gavin Fridell is a Canada Research Chair and Associate Professor in International Development Studies at St. Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Originally from Winnipeg, Fridell has written numerous books and articles about international development and trade, focusing on commodities such as bananas, wheat, coffee, and more recently, alcohol. His new book, Coffee, emphasizes the role of the state in the coffee trade. Sprudge contributor Nora Burkey spoke with Fridell this week about his research.

What led you to your fascination with coffee as a commodity?

You hear a lot of people who begin their journey because of a love for coffee. That wasn’t my story. I always had a love of world history, and although I’m not a historian—I am a political scientist—I originally started studying history. As I became more interested in social justice and the torturous history of commodities, I became fascinated by where our stuff comes from. I didn’t drink too much coffee when I started research. I have certainly upped my quality preference and increased my consumption since then, but that wasn’t the case when I began my journey!

Was there anything in particular that drew you to focus on coffee more so than other commodities?

Fair Trade drew me in initially, in a positive way. Over the years, my work became more cynical as I saw the limits of Fair Trade and similar programs. The history side in me has made me question things that are romantic, and instead find romance in things considered boring. Talking about the International Commodity Agreement (ICA)—which I do in my book Alternative Trade: Legacies for the Future—is generally not considered a very sexy thing to talk about, but talking about Fair Trade is pretty sexy. The ICA had its problems, but the average price of coffee from 1976-1989 was equal to and sometimes twice as high as what we call the Fair Trade price today, and it reached all the world’s 25 million coffee farmer families. Fair Trade reaches around 3%.

In Alternative Trade, you also discuss bananas and wheat along with your chapter on coffee and the ICA. Is your new book, Coffee, an elaboration of the coffee chapter?

My new book, Coffee, focuses on coffee and the state. The core argument is that the state has remained absolutely central to how the global coffee market runs. Vietnam, for example, went from having a small share in the global market to being one of the biggest players. That didn’t happen through market dynamics, it was led by the Vietnamese state. The state provided all the inputs, turned its small workers onto coffee, and provided them with almost everything they needed. The coffee industry in that country emerged as rapidly as it did because of the involvement of the state. It was a gamble, but they pulled it off. Now, the World Bank considers the Vietnamese state to offer some of the best credit to farmers in the world. Very often the state is used for bad, but it can also be used for good. Coffee economies that have thrived are those that recognized the role of the state and the benefits of relying on it, such as Colombia and Costa Rica.

What do you see as the state of environmental and political sustainability in the industry today?

The biggest issue nowadays is whether sustainability can truly be scaled up. There is an emerging consensus that we need to scale up our sustainability efforts and reach more farmers. Scaling up, however, usually means watering down. It means we need find a way to get as many bags in the world certified as sustainable, and that if we have to lower standards to do that, then we will. The International Coffee Organization (ICO) has picked up this issue in a noble way and I hope it can revive itself by taking a real leadership role.

Do you think much progress has been made in terms of sustainability since you first started writing about coffee?

I don’t think much progress has been made; we have just mastered the selling of progress. Being proposed in the industry today are the same solutions we’ve known about for years. If I break it down to two things we’ve been talking about since the 80s, they are productivity and quality. That has been the story for a long time. Unfortunately, farmers can spend a lot of time improving quality and productivity, but in the grand global context that’s not going to ensure economic sustainability for the small farmer. It works for the big players in the industry, and economic sustainability will certainly be ensured for those leaders. They’ll make tons of money in the next 15 years. Whether that’s true for coffee-farming families is a different story. Young people in coffee-producing countries don’t want to be farmers anymore. It makes sense. The only question is if they can find good jobs elsewhere. But it’s perhaps naïve to think the coffee industry will offer good jobs over the years, instead of the marginal jobs that are so often the norm.

Fair Trade does rely on the market and consumers to keep it going. How do you understand your work in light of that?

I have always considered my work to be in solidarity with what Fair Traders want to achieve. Fair Trade has always been grassroots, driven by the bottom up. That’s not the same thing that motivates corporate social responsibility. Those different motivations matter. In my experience, coffee trading the way we see it now is not what Fair Traders really want. We have all seen how the power of the global market can erode these projects despite the best intentions of their supporters. I still buy Fair Trade coffee, but I know that it’s not going to lift the world’s farmers out of poverty. You know, very often when I am interviewed people expect that I will be deeply cynical about consumers. Actually I am very sympathetic to consumers. The problem is we don’t live in a consumer culture; we live in a corporate culture. We blame the consumer for not wanting to pay more, but in reality the world is far more complex. On a $22 pair of jeans, the average consumer would have to pay 3 to 5 cents more to guarantee workers in Bangladesh fair wages, maternity leave, and decent working conditions. Most consumers would pay 3 to 5 cents more, but corporations don’t let them.

How do people do the right thing in this complex world?

People should buy ethical products, but we have to remember when we say that that there are only a few of us who have the time and resources to find out what is ethical and what is not. I think we need to stop thinking of ourselves as consumers of things like Fair Trade and instead see ourselves as citizens of it.

Will Coffee help us on the road to this citizenship?

I think the reason to read the book is for the emphasis on coffee statecraft. It doesn’t present a romantic idea of the state because the state has done horrible things. I think the question is if you want the state to work only for the rich and powerful, or do you want it to do something for you? History shows the more good things the state does for the coffee sector, the more successful coffee farmers will be.

You can pick up a copy of Fridell’s new book Coffee here.

Nora Burkey is a first time Sprudge contributor.